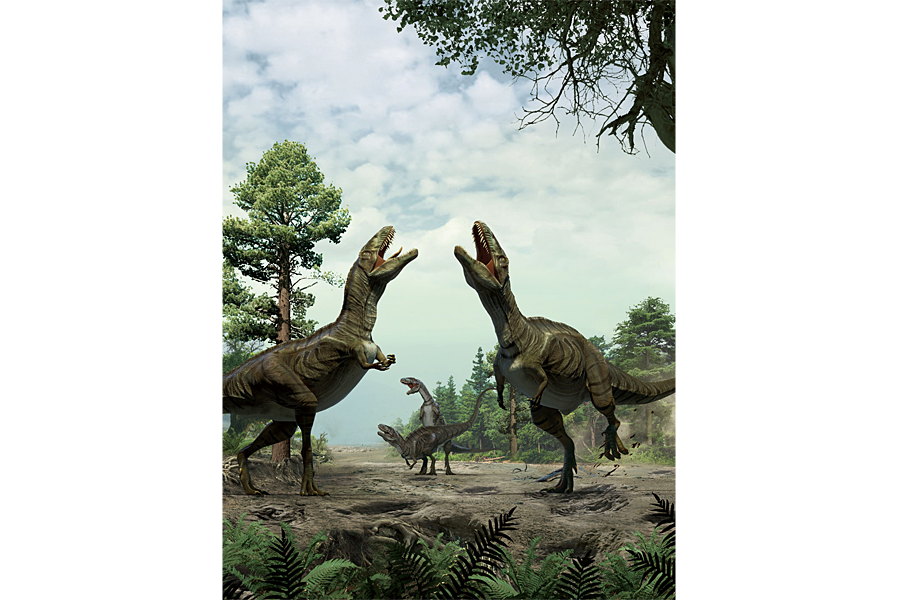

Did dinosaurs woo mates with fancy footwork?

Loading...

Researchers say that newly discovered funky dinosaur footprints may be traces of a frenzied Cretaceous courtship dance.

Some 100 million years ago, dinosaurs scratched up the ground in what is today Colorado. Scientists say the peculiar markings left behind could be direct evidence of the animals' mating behavior.

Of course, dinosaur behavior is difficult to reconstruct. When dinosaurs disappeared from Earth some 66 million years ago, they left little behind. Fossilized bones tell scientists little more than the prehistoric beasts' existence, so when it comes to understanding dinosaur mating behavior, researchers are often left speculating. But now, these theropod dinosaur footprints could provide evidence to back up scientists' speculations.

"We now have proof that carnivorous dinosaurs engaged in extremely active courtship displays," study lead author paleontologist Martin Lockley tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview.

These long, defined scratch marks could be the traces of a dynamic courtship dance, much like those employed by some modern ground-nesting birds, the researchers say in a paper published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

In what's called "nest scrape display" behavior, these birds dig at the dirt in a sort of pseudo-nest-building action.

"They're not building nests," Dr. Lockley explains. "But they're showing their partners that they can build nests." He adds that the birds' dance is quite frenzied and excited.

Matching motion to marks

Some of the scratch marks are around six feet long, Lockley says. The most defined tracks are made up of two long parallel furrows with a ridge in the middle. Clear scratch marks appear across the furrows.

To figure out how the dinosaurs made these marks, the researchers considered a few explanations.

"Could they be digging for water? That seems very unlikely," Lockley says. If the animals reached water, it would have filled the indentation and eroded the scratch marks.

Were they digging for food? Probably not, Lockley says. Theropod dinosaurs were carnivores and there are no skeletons that could represent a meaty snack that had been buried somehow.

The research team also considered that the dinosaurs were scratching the ground to leave some sort of scent to mark their territory, like some modern big cats, but the dinosaurs' only living descendants, birds, don't do this.

So by process of elimination and kinship, it came down to display behavior.

"These trace fossils of dinosaurs repeatedly scratching the ground are very likely from courtship behavior," Emory University paleontologist Anthony Martin, who was not involved in the study, tells the Monitor in an email. "Some modern birds do similar scratching when displaying or otherwise trying to attract a mate. Considering that modern birds are descended from Mesozoic theropod dinosaurs, it shouldn't be surprising that birds' ancient relatives would have done this, too."

Peter Falkingham, a paleontologist with Liverpool John Moores University who is not associated with the study, suggests that a direct comparison between the scrapes modern birds make during mating dances and these dinosaur marks would strengthen the paper.

"Footprints are always difficult because it's always hard to convince people of what you're seeing," Dr. Falkingham explains in an interview with the Monitor. He adds that some of his own papers have not convinced others.

"It can often be hard to find something completely new with footprints and say this shows us something we've never seen before," he says. "It's much more the case that footprints provide additional evidence, additional ideas that feed into other things we know."

But, dinosaurs are extinct, so scientists often rely on sparse fossil evidence and comparisons to modern animals.

Disappearing with a trace

Footprints are considered trace fossils, evidence left behind by an animal rather than parts of the animal itself. Scientists use trace fossils as clues to reconstruct the lives and behaviors of ancient, extinct animals.

"The mindset is that if you can find a complete skeleton, or a relatively complete skeleton, you can reconstruct the whole animal and stick it in a museum," Lockley says. "But I like to tell my colleagues that study dinosaur bones, you're studying death, decay, destruction, putrefaction. We're studying the living, dynamic, athletic animal and its behavior."

Dinosaur footprints have helped scientists learn about how fast an animal could run, or if they were social animals. Other trace fossils, like bite marks, have suggested how and what certain dinosaurs ate.

"Trace fossils are your evidence of something happening other than an animal existing, which is what its bones tell you," Falkingham explains. Sure, bones can suggest how an animal might have been able to move, he says, but trace fossils are physical evidence of what movements they actually made.

As Lockley says, "This is fossilized behavior."