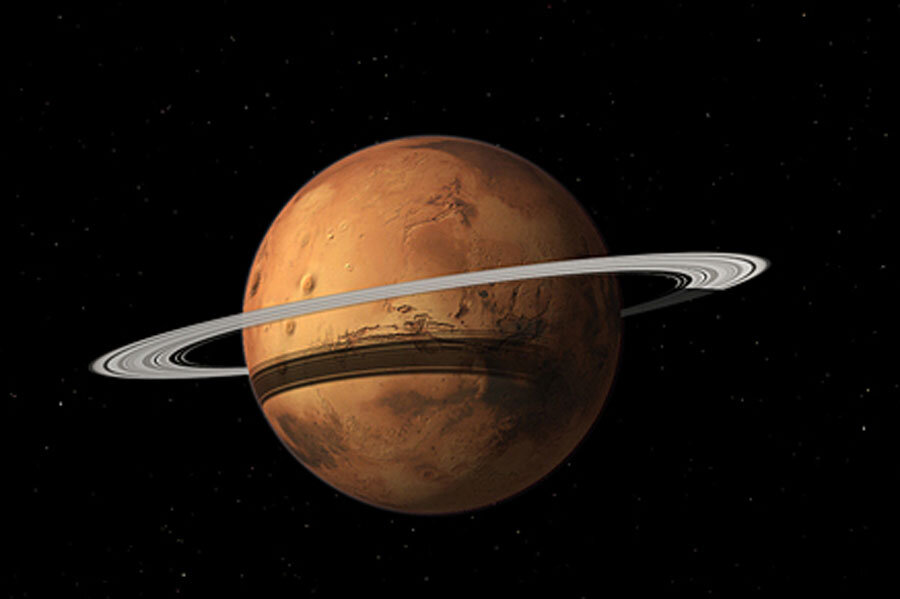

Could Mars someday get its own set of rings?

Loading...

Mars may one day have rings similar to Saturn's famous halo, new research suggests.

In a few tens of millions of years, the Red Planet may completely crush its innermost moon, Phobos, and form a ring of rocky debris, according to the new work. Phobos is moving closer to Mars every year, meaning the planet's gravitational pull on the satellite is increasing. Some scientists have theorized that Phobos will eventually collide with Mars, but the new research suggests that the small moon may not last that long.

"The main factor affecting whether Phobos will crash into Mars or break apart is its strength," Tushar Mittal, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley and one of the authors of the new research paper, told Space.com by email. "If Phobos is too weak to withstand increasing tidal stresses, then we expect it to break apart." [Photos of Mars' Moon Phobos Up Close]

Strength of a satellite

The two moons of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, are named after the children of the god Ares, the Greek counterpart to Mars, the Roman god of war.

The larger, inner moon, Phobos, is only about 14 miles (22 kilometers) wide, and orbits the Red Planet rapidly, rising and setting twice each Martian day. The tiny moon is slowly moving toward its host — drawing closer to Mars by 6.5 feet (2 meters) every century — which may result in a dramatic crash into the Martian surface within 30 million to 50 million years, previous research has shown.

But after simulating the physical stresses that Mars exerts on Phobos, Mittal and co-author Benjamin Black, a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, see a different fate for Phobos. Their research suggests that instead of going out in a single, enormous impact, the moon will be pulled apart by the Martian gravity.

On Earth, the gravitational pull of the moon causes the rise and fall of ocean tides. Although the moon has no oceans, Earth's gravitational pull is still referred to as "tidal forces."

Phobos and other moons in the solar system also feel tidal stress from their hosts. Black and Mittal studied the "strength" of the Martian satellite, including characteristics like composition and density, to determine how much planetary stress the moon could withstand.

After comparing it to several meteorites on Earth, they concluded that Phobos today is made up of porous, heavily damaged rock and is likely the same throughout its interior.

"The moon is probably neither a complete rubble pile, nor completely rigid," Mittal said. "The porosity of Phobos may have helped it survive."

After simulating the stresses caused by the tidal pull of Mars, the pair found that the moon would break up over the course of 20 million to 40 million years, forming a ring of debris around the planet.

The rubble would continue to move inward, toward the planet, though at a slower pace than the larger moon is traveling, they said. Over the span of 1 million to 100 million years, the particles would rain down on the equatorial region of Mars, Mittal and Black said.

Initially, the ring could be as dense as Saturn's, but it would become thinner as the particles fell down onto the planet over time, they added. [Latest Images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter]

An inward-moving planet

Saturn isn't the only planet in the solar system to boast rings; all of the gas giant planets have some form of debris disk surrounding them. While some of the material was likely gathered from space, portions of those ring systems could be the remains of early moons that broke apart as they journeyed inward. Larger moons move inward at a faster pace than their smaller counterparts, causing a much more rapid demise.

"Phobos is unique in that it is currently one of only a couple of inwardly evolving moons in our solar system that we know about," Mittal said. "However, since inwardly evolving moons inadvertently self-destruct, it is possible that more inwardly migrating moons may have existed in the past."

Phobos is the only remaining inwardly migrating moon known to exist today. The tiny, doomed moon may help scientists to better understand the evolution of the early solar system and the fate of other moons already destroyed.

What would a ring on Mars look like?

For an observer standing the surface of Mars, the ring will look different depending on her location.

"From one angle, the ring will reflect extra light towards a viewer, and it will look like a bright curve in the sky," Mittal said. "From another angle, the viewer might be in the ring's shadow, and the ring would be a dark curve in the sky."

Because Phobos is made up of dark material that doesn't reflect light well, the ring might be difficult to spot from Earth with an amateur telescope. However, Mittal suggested that the ring's shadow on Mars could be visible.

Confined to a single, stable disk, the ring — if it forms — shouldn't create too many problems for theexploration of, or travel to, the Red Planet, Mittal said. However, "Any deorbiting ring particles could be a potential hazard for a Mars base built near the equator," he added.

The research was published online today (Nov. 23) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- Wow! Curiosity Rover Captures 2 Mars Moons Together In Stunning NASA Video

- Curiosity Sees Martian Moons: Phobos and Deimos | Time-Lapse Video

- How the Mars Moon Phobos Got Its Grooves

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.