How our view of Mars has changed

Loading...

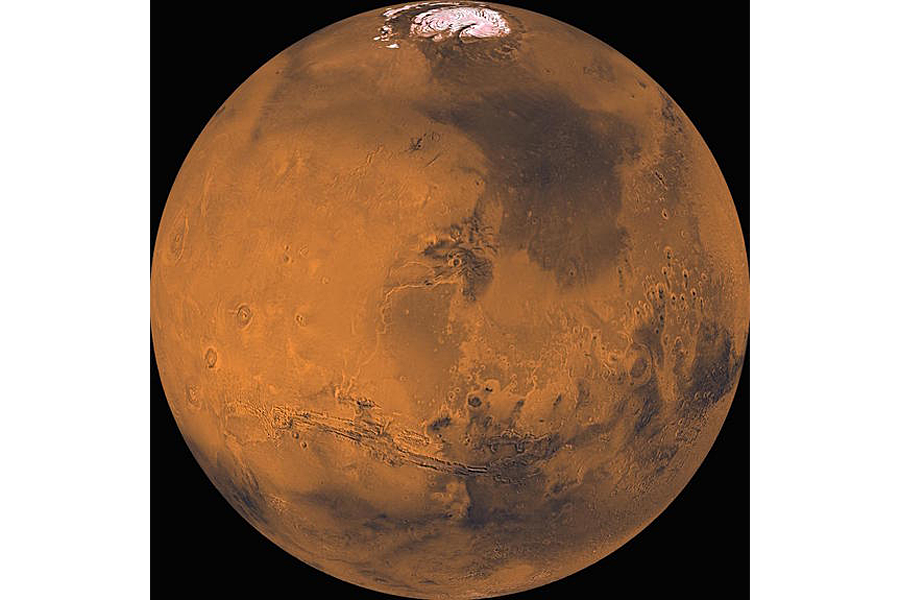

The dusty-red sphere now called Mars has fascinated stargazers since the dawn of humanity, but Earthlings' view of the planet has changed drastically over the years. Once thought of as a lush alien world teeming with life, it was later dismissed as an arid, desolate orb. But now, scientists have announced the Red Planet has long, fingerlike strips of seeping, salty, liquid water that just might aid in the search for extraterrestrial life.

The finding, revealed Monday (Sept. 28) by NASA scientists, once again changes the way people view the bright-red planet, Mars experts told Live Science.

The ancient Greeks and Romans named Mars — a planet barely more than half Earth's size — after the god of war. But they likely didn't realize it was another world, with two moons to boot, said Bruce Jakosky, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. [In Photos: Is Water Flowing on Mars?]

In the 1600s and 1700s, astronomers tinkered with nascent telescopes and discovered that Mars, like Earth, was a planet and had a roughly 24-hour day-and-night cycle. At this time, people assumed intelligent beings were scampering over the Martian surface, Jakosky said.

Early astronomers had other fanciful, and often mistaken, views of Mars. In 1784, the British astronomer Sir William Herschel wrote that the dark areas on Mars were oceans, and the light areas land. He also speculated the planet was home to aliens, who "probably enjoy a situation similar to our own," according to NASA. (He also apparently thought intelligent life was living under the sun's surface in a cool spot, NASA reported.)

In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli reported seeing grooves or channels on Mars with his telescope. Schiaparelli called these features "canali," which can mean "natural channels" in Italian. The word was mistakenly translated into "canals" in English, a phrasing that suggested handiwork by living beings. American businessman and astronomer Percival Lowell popularized the idea, and wrote three books about aliens that likely created the canals to survive on a drying planet.

"The canals were an attempt, [Lowell] thought, by intelligent beings to carry water from the poles, where there was water, to the rest of the planet," said Richard Zurek, chief scientist for the Mars Program Office at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

It wasn't until NASA's Mariner space missions in the 1960s and 1970s that researchers could confidently prove there were no alien-made canals, Zurek said.

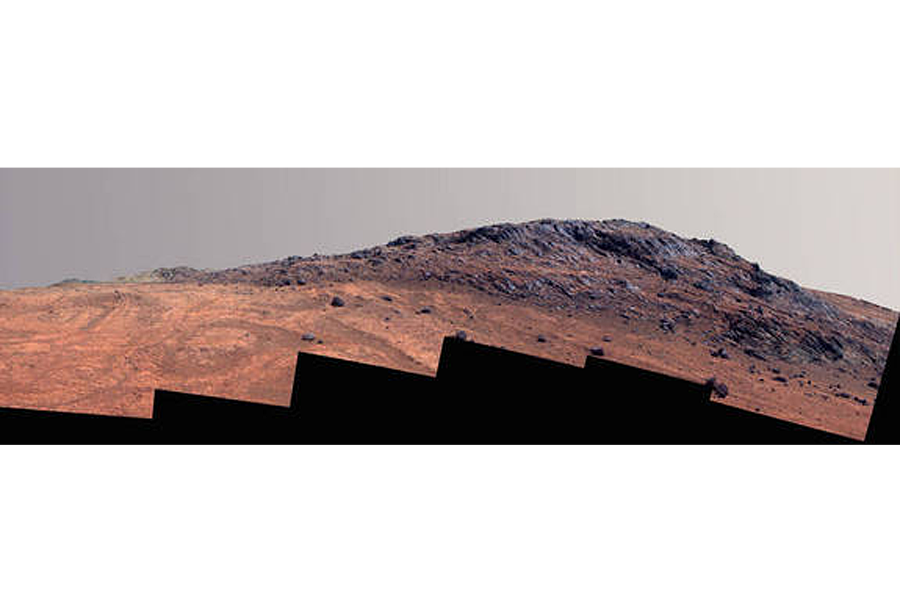

"We almost went to the other extreme, because we saw a hilly, cratered landscape on the first flybys of the planet," Zurek told Live Science, referring to the Mariner 4 mission. "That suggested it was more like the moon than it was like the Earth."

Until then, scientists had speculated that Mars had a thick atmosphere that could trap heat and help the planet support life at its distant location from the sun. Mars orbits at about 142 million miles (229 million kilometers) from the sun, compared with Earth's 93-million-mile (150 million km) leap from the sun. But this wasn't the case; Mars' atmosphere is about 100 times thinner than the gas layer surrounding Earth, partially explaining why the Red Planet is such a cold, barren place, Jakosky said.

"All the way up through [NASA's] Mariner 6 and 7 in 1969, you could think of the potential for life on Mars as declining," Jakosky said. "In 1971, we orbited the Mariner 9 spacecraft, and that changed things. It took global pictures of Mars, and we saw things that looked very Earth-like, including streambeds, river channels and volcanoes. People thought, 'Well, maybe there's the potential for liquid water and potential for life after all.'"

In the 1970s, the NASA Viking missions landed on Mars and took samples of the soil to look for signs of microbial life. But they recorded none, Jakosky said. In fact, the Viking mission scientists called Mars "self-sterilizing," describing how the combination of the sun's UV rays and the chemical properties of the soil prevented life from forming in those soils, according to NASA. [Seeing Things on Mars: A History of Martian Illusions]

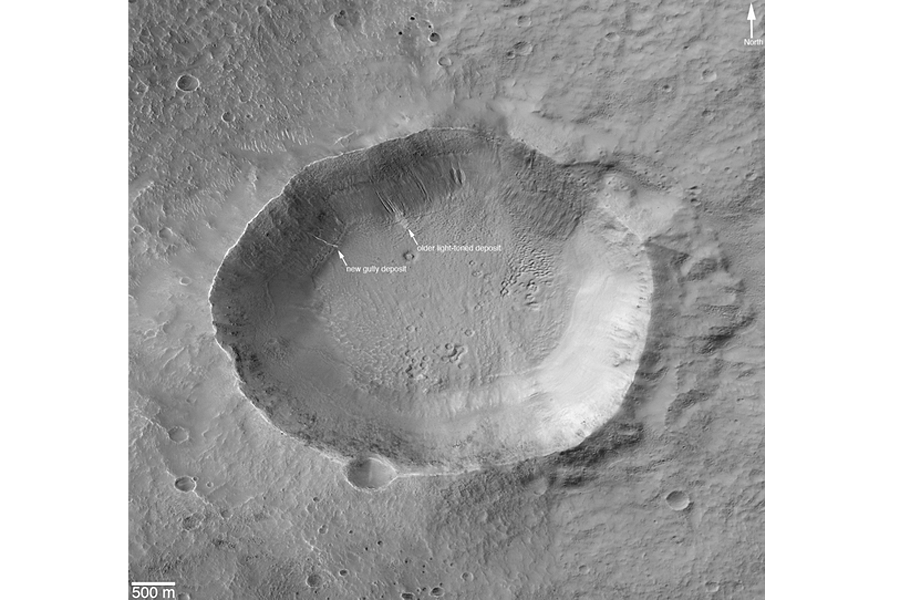

Spacecraft in the 1990s renewed the search for water. The Mars Global Surveyor orbited the planet and took high-resolution images of the surface, finding evidence of ancient gullies. Additional watery evidence came from Martian meteorites that have smashed into Earth, carrying telltale signs of liquid flowing through them, Jakosky said.

Since then, robotic missions have scoured the Red Planet for signs of liquid water. Frozen water is locked up in Mars' roughly mile-thick (1.6 kilometers) ice caps, and enough water vapor resides in the atmosphere to form clouds. Even so, liquid water is more elusive, Zurek said.

Perhaps Mars had water millions or billions of years ago, but that water has since frozen on the surface or been lost to space, Zurek said. (The NASA spacecraft Maven is already examining the Martian atmosphere and helping scientists decipher how Mars lost its water, if that did happen, he said.)

The new finding gives researchers a good spot to look for life on Mars, Zurek said. But the newfound salty streaks aren't like rivers that flow on Earth, he cautioned. [5 Mars Myths and Misconceptions]

"If I pour pure liquid water out on the [Martian] surface today, it's either going to boil way into the atmosphere or it's going to freeze there on the surface," he said.

Any water on Mars is likely laden with salts called perchlorates, which lower water's freezing point to about minus 70 degrees Celsius (minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit), Zurek said.

Moreover, the liquid water — if indeed it is that — only appears during the warm seasons, he said.

"These features grow in a slow, seasonal kind of way, not in a rapid outburst of a flow or a stream," Zurek said. "But nevertheless, here's a source of water that could be staying liquid for a time on the planet."

Extremely salty water isn't necessarily good for life, but perhaps extremophiles can live in those environments, he said.

"We don't know what the evolution of life might have been on the planet, if it ever originated," Zurek said. "But at least this tells us some places where we could go look for evidence of this. It is briny, and there may not be much of it, but it is a place that we could go look."

In a way, the discovery isn't so different from what astronomers were looking for years ago, he said.

"It's not that ancient canal network delivering massive amounts of water out to the desert, but it's curious the way that those early themes over 100 years ago are still playing today," Zurek said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Mars Hoaxes! 6 Stubborn Red Planet Conspiracy Theories

- 7 Most Mars-like Places on Earth

- 7 Theories on the Origin of Life

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.