Scientists unlock secrets of dinosaurs' powerful chomp

Loading...

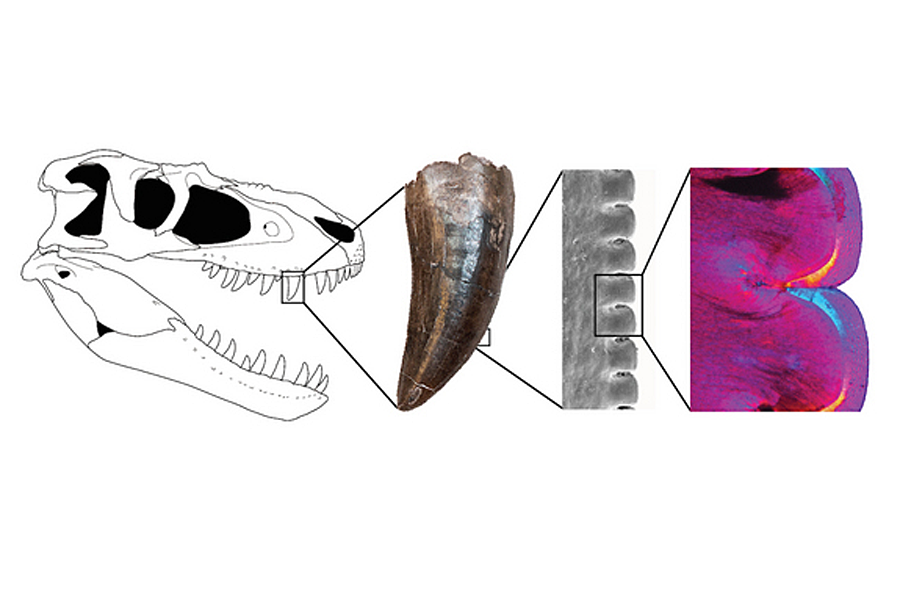

Secret structures hidden within the serrated teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex and other theropods helped the fearsome dinosaurs tear apart their prey without chipping their pearly whites, a new study finds.

Researchers looked at the teeth of theropods — a group of bipedal, largely carnivorous dinosaurs that includesT. rex and Velociraptor — to study the mysterious structures that looked like cracks within each tooth.

The investigation showed that these structures weren't cracks at all, but deep folds within the tooth that strengthened each individual serration and helped prevent breakage when the dinosaur pierced through its prey, said study lead researcher Kirstin Brink, a postdoctoral researcher of biology at the University of Toronto Mississauga. [Image Gallery: The Life of T. Rex]

The new study upends one from the early 1990s, Brink said. Researchers first noticed these cryptic cracks on the tooth of a T. rex cousin named Albertosaurus about two decades ago.

Initially, the researchers thought the cracks were signs of damage, likely acquired when the dinosaur ate a hearty meal. But the new analysis finds that isn't the case, Brink said.

"I sectioned teeth from eight other theropods besides Albertosaurus, and found that the structure is actually in all theropods, and it's not actually a crack," she told Live Science.

Serrated teeth

The study actually began with a Dimetrodon, a Paleozoic animal with serrated teeth that lived before the time of the dinosaurs. When Brink sliced the Dimetrodon tooth in half and compared it with the serrated teeth of dinosaurs, she found they had different internal structures.

"They look very similar on the outside," Brink said. "It's only when you cut them open [that you see] that they're completely different."

Curious, she obtained two to three teeth from eight different theropods species, including T. rex, Coelophysis bauri and Carcharodontosaurus saharicus. She also looked at specimens of theropod teeth that had not yet fully matured and erupted past the gum line, meaning, "they had not been used for feeding," Brink said.

An analysis using a scanning electron microscope and a synchrotron (a microscope that helps determine the chemical composition of a substance) showed that each tooth, even the ones that had not yet erupted, had these cracklike structures next to each serration, she said. This debunked the idea that the cracks were artifacts of eating a meaty meal, she said.

Furthermore, each structure has a few extra layers of calcified tissue, called dentine, under the tooth's outer enamel coating, making it tough and hard.

"We proposed a developmental hypothesis that these are structures created when the tooth is first forming," Brink said. "It actually helps to deepen the serration within the tooth and strengthen each serration and the tooth overall."

Serrated teeth help animals pierce through flesh and hold onto chunks of meat. The formations, which the researchers call "deep interdental folds," strengthen the serrations. In fact, they likely helped theropods survive as top predators for about 165 million years, Brink said.

Serrated teeth still exist today in Komodo dragons. However, Komodo dragon teeth don't have deep interdental folds, nor do they have the extra layers of dentine that would strengthen their bite, Brink added.

She called the toothy finding fascinating and "unexpected."

"It's really cool that such a small, little change in the tooth structure, a small arrangement of the dental tissues, could completely change the ways these animals are living," she said.

The study was published online today (July 28) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Photos: One of the World's Biggest Dinosaurs Discovered

- 7 Surprising Dinosaur Facts

- Photos: 7-Year-Old Boy Discovers T. Rex Cousin

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.