Exotic hadron particles detected at CERN: Bizarre matter defies known physics

Loading...

The existence of exotic hadrons — a type of matter that doesn't fit within the traditional model of particle physics — has now been confirmed, scientists say.

Hadrons are subatomic particles made up of quarks and antiquarks (which have the same mass as their quark counterparts, but opposite charge), which interact via the "strong force" that binds protons together inside the nuclei of atoms.

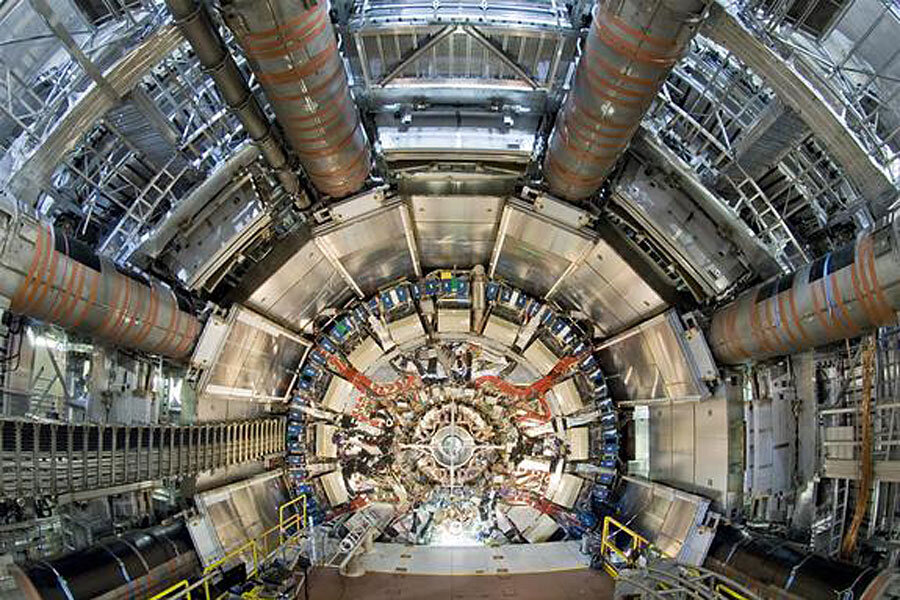

Researchers working on the Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) collaboration at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland — where the elusive Higgs boson particle was discovered in 2012 — announced today (April 14) they had confirmed the existence of a new type of hadron, with an unprecedented degree of statistical certainty. [Standard Model of Particle Physics Explained (Inforgraphic)]

"We've confirmed the unambiguous observation of a very exotic state — something that looks like a particle composed of two quarks and two antiquarks," study co-leader Tomasz Skwarnicki, a high-energy physicist at Syracuse University in New York said in a statement. The discovery "may give us a new way of looking at strong-[force] interaction physics," he added.

The Standard Model of particle physics allows for two kinds of hadrons. "Baryons" (such as protons) are made up of three quarks, and "mesons" are made up of a quark- antiquark pair. But since the Standard Model was developed, physicists have predicted the existence of other types of hadrons composed of different combinations of quarks and antiquarks, which could arise from the decay of mesons.

In 2007, a team of scientists called the Belle Collaboration that was using a particle accelerator in Japan discovered evidence of an exotic particle called Z(4430), which appeared to be composed of two quarks and two antiquarks. But some scientists thought their analysis was "naïve" and lacked good evidence, Skwarnicki said.

A few years later, a team known as BaBar used a more sophisticated analysis that seemed to explain the data without exotic hadrons.

"BaBar didn't prove that Belle's measurements and data interpretations were wrong," Skwarnicki said. "They just felt that, based on their data, there was no need to postulate existence of this particle."

So the original team conducted an even more rigorous analysis of the data, and found strong evidence for the particle.

Now, the LHCb team has studied data from more than 25,000 meson decay events selected from data from 180 trillion proton-proton collisions in the Large Hadron Collider, the world's largest and most powerful particle accelerator. They analyzed the data using both the Belle and BaBar teams' methods, and confirmed the particle was both real and an exotic hadron.

The results of the experiment are "the clincher" that such particles do exist, and aren't just some artifact of the data, Skwarnicki said.

His colleague, Sheldon Stone of CERN, also praised the achievement. "It's great to finally prove the existence of something that we had long thought was out there," he said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

- Beyond Higgs: 5 Elusive Particles That May Lurk in the Universe

- Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles in Nature

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.