Ravenous galaxy devours neighbor, leaves crumbs

Loading...

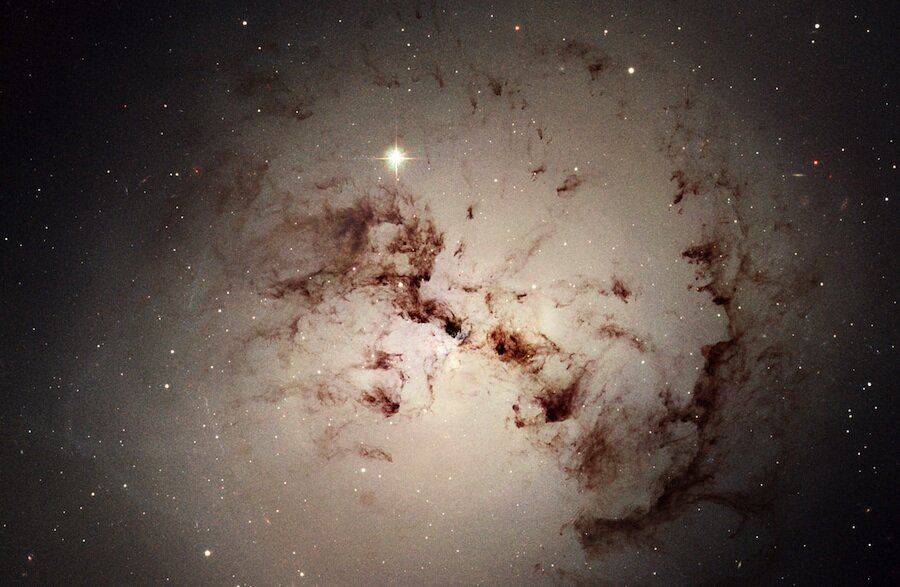

Astronomers have pieced together an image of a distant and voracious galaxy that appears strewn with the remains of other galaxies it has devoured. The evidence, as reported by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), has the poetry of a creation story: "Wisps and shells of stars that have been torn from their original locations and flung into intergalactic space."

But this is a story of demolition, with a black hole as its wrecking ball.

NGC 1316 is a "radio galaxy," meaning that its black hole, fed on a robust diet of intergalactic matter, generates intense heat and radio waves potent enough to be measured by astronomers some 60 million light years away.

The "wisps" detected in this new image are ribbons of dust and tiny star clusters wending through the galaxy, suggesting that NGC 1316's most recent meal was a dust-rich spiral galaxy. And the "shells" are not remnants of individual stars, but swaths of ejected stars that encase the galaxy.

"When one galaxy passes through and is eaten by another, you could imagine it a little bit like dropping a pebble into a pool full of water," explains ESO spokesman Richard Hook. "You get ripples of large numbers of stars that are being driven out of the galaxy, to become these shell-like features we see."

Gravitational attraction brings galaxies toward NCG 1316, whose "supermassive black hole" helps tear them asunder. Its last engulfment happened an estimated 3 billion years ago, but astronomers interpret these signs – including the intense heat of its black hole – as evidence that "the disruptive behavior is continuing."

To create such a detailed image of a far-away subject, ESO astronomers combined multiple images gathered by a huge 2.2-meter telescope at Chile's La Silla Observatory. "It's more or less the same as taking a very long exposure," says Hook.

NCG 1316 is the brightest source of radio emissions in its constellation, named Fornax, and the fourth brightest source of radio emissions in the known sky, thanks to its well-fed black hole.

Our own Milky Way has a black hole too – an enormous one, in fact, roughly 4 million times the mass of our sun. But ours is faint with hunger, emitting much less radiation than a typical black hole of its size. Just last week, news that a dusty gas cloud was barreling toward it inspired a flurry of science reports, excited that our beast might finally get a morsel of its own.

The Milky Way doesn't seem to be in imminent danger from NCG 1316, thanks to the 60 million light years separating us. But Mr. Hook says that seeing the aftermath of that galaxy's last "merger" has expanded astronomers' understandings of how galaxies change. And that information may come in handy for posterity.

"Our galaxy hasn't been through a major merger yet," he says, "but it will do in about 4 billion years when we merge with the Andromeda Galaxy."