Sun unleashes humongous flare

Loading...

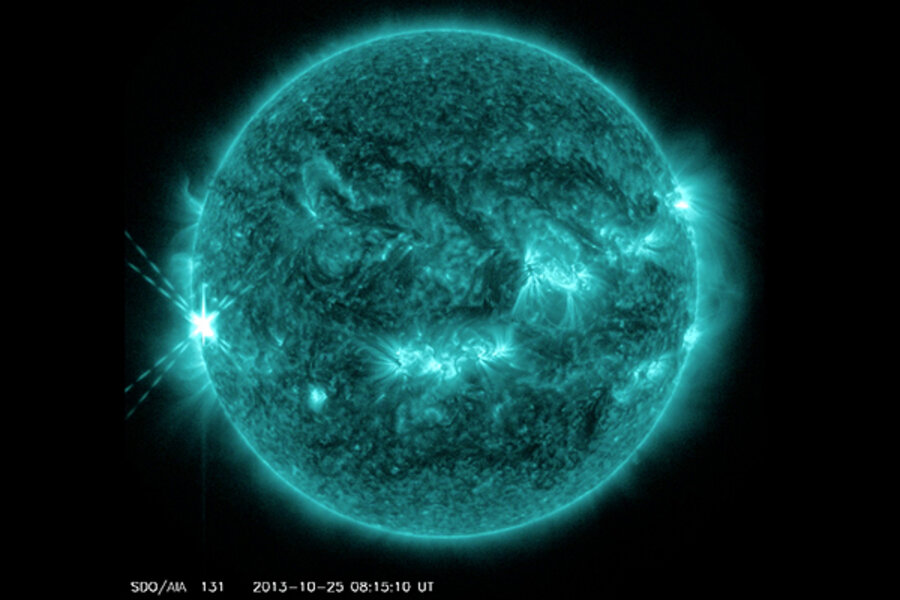

The sun erupted with one of the strongest solar flares it can unleash early Friday (Oct. 25), just days after firing off an intense solar storm at Earth.

The major solar flare, which registered as an X1.7-class solar event on the space weather scale, peaked at 4:01 a.m. EDT (0801 GMT), according to an alert by the NOAA-run Space Weather Prediction Center. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory captured video of the X1.7 solar flare, which followed several smaller sun storms over the last few days.

The sun storm erupted from a new sunspot cluster called Region 1882 and sparked a temporary radio blackout, SWPC officials said in an update. But it is not aimed directly at Earth and is not currently expected to be "geo-effective," meaning that it should not spark a major geomagnetic storms in Earth's magnetic field, they added. [Solar Max: Sun Storm Photos of 2013]

Astronomers classify solar flares into three categories — C, M and X — with C being the weakest and X the strongest. When aimed directly at Earth, X-class sun eruptions can interfere with satellite-based communications and navigation systems, endanger astronauts in orbit.

That does not appear to be the case with the X1.7-class flare, according to an SWPC update, though officials are awaiting additional imagery of the solar flare to see if it was associated with a massive explosion of super-hot plasma — known as a coronal mass ejection — that can hurl solar material into space at more than 1 million mph.

Friday's X1.7 solar flare occurred just hours after a more moderate M-class solar flare and two days after an intense M9.4-class solar flare on Wednesday (Oct. 23). That M9.4 solar flare was associated with a coronal mass ejection.

The Wednesday sun storm peaked at 8:30 p.m. EDT on Oct. 23 (0030 GMT Thursday), with NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory capturing an impressive close-up video of that solar flare. Flares similar to the one that erupted Wednesday evening have caused brief radio blackouts near the poles in the past, NASA officials said.

"Increased numbers of flares are quite common at the moment, since the sun is near solar maximum," NASA officials wrote Thursday while discussing the Oct. 23 solar flare. "Humans have tracked solar cycles continuously since they were discovered in 1843, and it is normal for there to be many flares a day during the sun's peak activity."

The coronal mass ejection associated with Wednesday's flare appears to be Earth-directed, but it's relatively weak. Powerful eruptions that hit Earth can wreak havoc temporarily, triggering geomagnetic storms that can disrupt radio communications, GPS signals and power grids. Such events can also dramatically ramp up Earth's auroras, also known as the northern and southern lights.

The arrival of several other recent CMEs is imminent, however, so skywatchers at high latitudes should keep an eye out. The fallout from those solar storms are expected to spark a G1 geomagnetic storm on Earth today, SWPC officials said.

"Earth's magnetic field is about to receive a glancing blow from three CMEs observed leaving the sun between Oct. 20th and 22nd," astronomer Tony Phillips wrote Thursday (Oct. 24) on Spaceweather.com, a website that tracks skywatching and space weather events.

"Forecast models suggest that the three clouds merged en route to Earth, and their combined impact could trigger a mild polar geomagnetic storm on Oct. 24-25," Phillips added. "High-latitude sky watchers should be alert for auroras."

This storm should be minor and brief, according to forecasters with the Space Weather Prediction Center, which is run by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They predict a short-lived G1 geomagnetic storm — which can cause weak power grid fluctuations, minor impacts on satellite operations and intensified auroras — today (Oct, 25), then another one on Monday (Oct. 28).

The sun is in the peak year of its current 11-year activity cycle, which is known as Solar Cycle 24. The number of sunspots increases during a solar maximum, leading to more flares and CMEs, which erupt from these temporary dark (and relatively cool) patches on our star.

The sun has been quiet during its current cycle, and the peak has been lackluster so far as well. In fact, scientists say Solar Cycle 24's maximum is the weakest in the last 100 years or so.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing aurora photo from the upcoming geomagnetic storms and you'd like to share it for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall (@michaeldwall and Google+) contributed to this report.Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

- Powerful X-Flare Erupts From Active Sunspot | Video

- The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History

- Anatomy of Sun Storms & Solar Flares (Infographic)

- Attack of the Sun | Video Show

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.