Kepler has made an array of stunning discoveries – from oddball solar systems to sun-scorched planets that orbit their stars in less than an Earth day. But Kepler-22b was the first discovery that truly validated the mission.

The goal for Kepler has always been to find Earth-mass planets orbiting sun-like stars at Earth-like distances. In other words, to find Earth's cosmic twins. Kepler-22b was perhaps a bit more like a big brother – it's larger than Earth – but its discovery was proof that Kepler was on the right track.

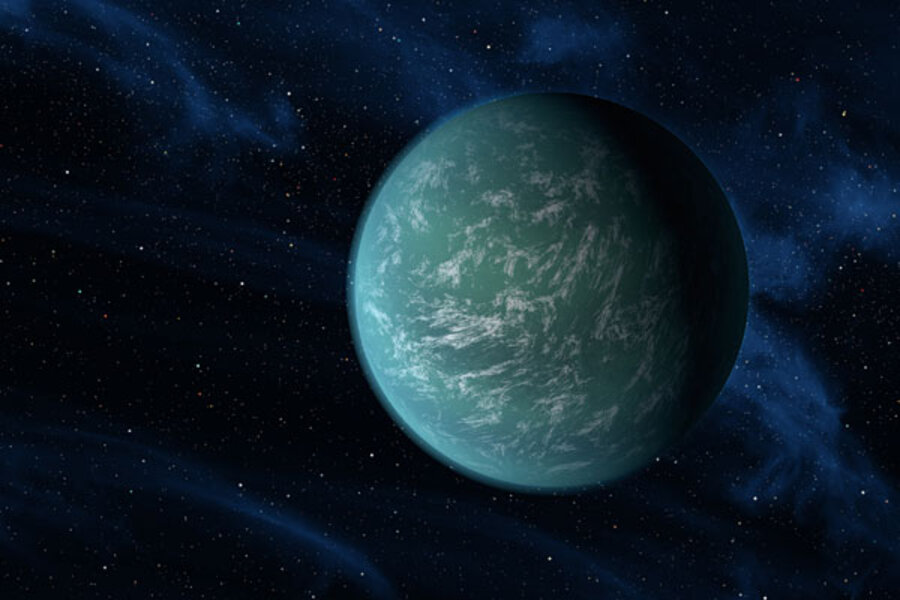

Scientists announced the discovery of Kepler-22b in December 2011. It was smack dab in the middle of its star's so-called habitable zone – the "Goldilocks zone" close enough to allow water to be liquid but far enough to ensure that it didn't burn off. Kepler-22b orbits its sun once every 290 days. Moreover, its sun is the same G-type star as our sun, though slightly smaller and cooler.

The planet itself has a radius 2.4 times larger than Earth. Scientists are not sure about the composition of the planet, but some have suggested it could be a mini-Neptune with a global ocean and a rocky core. If it has an atmosphere, the temperature could be 72 degrees F.

"It's so exciting to imagine the possibilities," Natalie Batalha, the Kepler deputy science chief, told the Associated Press in 2011. Floating on that "world completely covered in water" could be like being on an Earth ocean, and "it's not beyond the realm of possibility that life could exist in such an ocean."