Ancient, fossilized, insect-like brain surprisingly complex

Loading...

The oldest brain ever found in an arthropod — a group of invertebrates that includes insects and crustaceans — is surprisingly complex for its 520-million-year age, researchers report today (Oct. 10).

The fossilized brain, found in an extinct arthropod from China, looks very similar to the brains of today's modern insects, said study researcher Nicholas Strausfeld, the director of the Center for Insect Science at the University of Arizona.

"The rest of the animal is incredibly simple, so it's a big surprise to see a brain that is so advanced, as it were, in such a simple animal," Strausfeld told LiveScience.

The discovery suggests that brains evolved a complex organization early on in history, he added.

The evolving insect brain

Arthropods include any animal with an exoskeleton, jointed legs and a segmented body, from lobsters to scorpions to beetles to butterflies. There is controversy about how these various creatures evolved, however. One theory holds that insects evolved from ancestors not unlike today's branchiopods, which are extremely simple crustaceans such as fairy shrimp and water fleas. Branchiopods have simpler brains than insects and higher crustaceans, Strausfeld said, so this theory of evolution holds that both higher crustaceans and insects evolved very similar complex brains after splitting off from this common branchiopod-like ancestor. [Dazzling Photos of Dew-Covered Insects]

Alternatively, all of these groups — insects, branchiopods and higher crustaceans — could have evolved from an ancestor with a complex brain, with branchiopods regressing later.

"So the question was, 'What was the early brain, what did it look like? Did it look simple or did it look complex?'" Strausfeld said.

That's not an easy question to answer, given that brains rarely get fossilized. But Strausfeld's earlier work on arthropod fossils convinced him it could be done. He just had to go to China, home of an amazing collection of stunningly preserved ancient fossils.

Last-minute discovery

In China's Yunnan province, paleontologists have long uncovered fossils from the Cambrian period, which ran from about 542 million to 488 million years ago. These fossils are very well-preserved.

For five days, Strausfeld and his colleagues poured through fossils, searching for dark silhouettes of preserved brains inside ancient arthropod heads. There was one fossil that remained elusive, however: A specimen Strausfeld had read about in a paper by Swedish researchers. They thought they'd seen a fossilized brain.

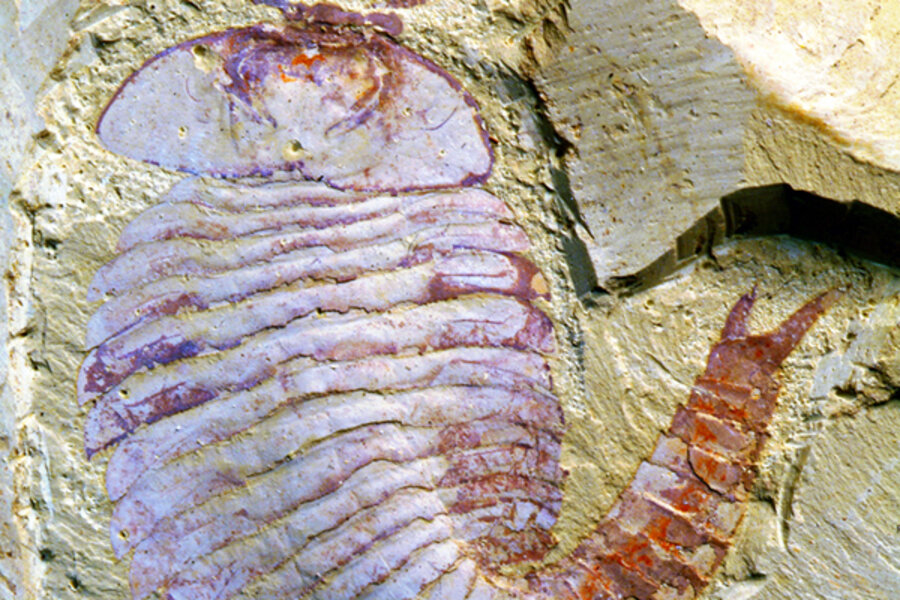

With only a few hours left in the lab, Strausfeld's colleague, Xiaoya Ma, of the Natural History Museum in London went hunting for the missing specimen. An hour and a half later, she returned with the fossil, an extinct armored creature just a few centimeters long called Fuxianhuia protensa. [25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"I looked at the microscope and I think I said something like, 'Whoopee, I think we've got the crown jewels!'" Strausfeld said. Under magnification, he could see the dark brown silhouette of preserved brain nestled in the arthropod's skull.

"It's pretty bloody marvelous, actually. … I was sitting looking at the thing, going, 'Oh my goodness gracious,'" Strausfeld said. With only five hours left before he had to leave to give a scheduled talk and fly home, Strausfeld got busy photographing the discovery.

An analysis of the brain revealed it to be in three parts, just as the brains of modern insects are in three parts (known as the protocerebrum, deutocerebrum and tritocerebrum). Nerves from the eyes extend into the protocerebrum, nerves from the antennaes feed into the ancient creature's deutocerebrum, and a third nerve root from further back in the body extends into the tritocerebrum. The researchers report the findings in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

This complex, insectlike brain suggests that rather than insects arising from simple branchiopods, today's arthropods descend from a complex-brained ancestor. Branchiopods would later have shed some of this complexity, Strausfeld said, while other crustaceans and insects kept it. In fact, he said, the brain may have evolved to segment into three parts very early on; mammals, including humans, have a forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain, suggesting a common organization.

"Lots of people don't like that idea, sharing a brain with a beetle, but there's good evidence suggesting that you do," Strausfeld said.

Bug brains may seem simple to us, but arthropods are at the base of many a food chain, making them crucial creatures, Strausfeld said. He and his team plan to return to China to hunt out more ancient arthropod brains.

"What we want to do, of course, is go deeper in time," Strausfeld said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.