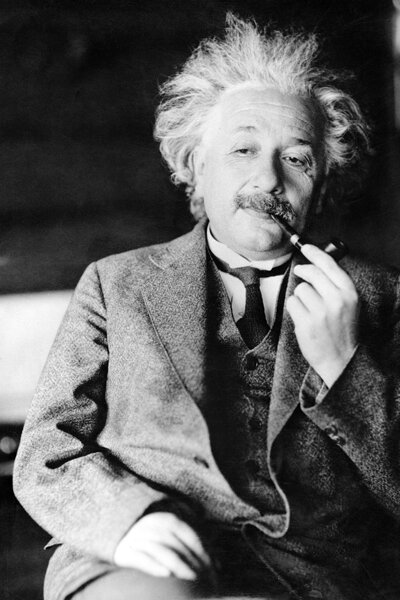

Albert Einstein had problems with authority in school, new online archives reveal

Loading...

Now anyone with Internet access can peek into one of the most celebrated minds in science.

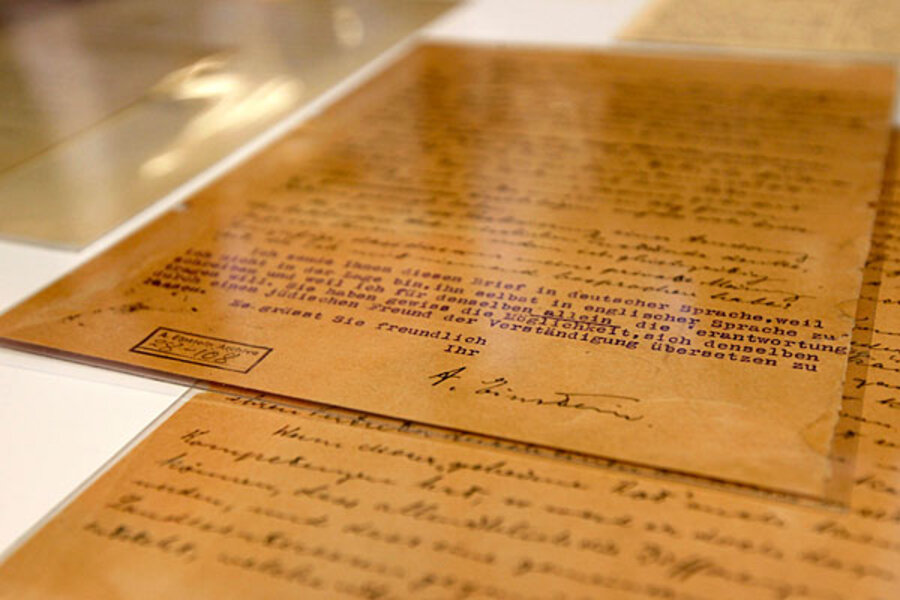

Albert Einstein's complete archive is gradually becoming available through the Einstein Archives Online. On Monday (March 19), the online archive debuted with roughly 2,000 documents, and the archival database lists all of the more than 80,000 documents that will ultimately be available. [Einstein's 'Biggest Blunder' Turns Out to Be Right]

The documents — everything from personal letters to scientific manuscripts — are held by the Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at the Einstein Papers Project at the California Institute of Technology.

The site's gallery offers viewers a peak at Einstein's high school certification, which he received upon finishing high school at 16 in 1896. It turns out Einstein was an excellent student, not a terrible one, as often said. However, according to the archives, he left because he couldn't handle the strict discipline and authority.

The archive also contains images of one of only three existing manuscripts containing the famous E=mc^2 equation written in Einstein's handwriting. This equation, which describes the relationship betweem energy, mass and the speed of light, derives from his theory of special relativity. His 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics is also on display.

On the personal side, the archive contains a postcard to his mother Pauline in September 1919, which spoke of results of his research, led by British astronomer Arthur Eddington, during the May 1919 solar eclipse; this data confirmed a prediction made by the general theory of relativity. It also spoke of his mother's pain as her health deteriorated. The letter began: "Dear Mother, Good news today. H.A. Lorentz has telegraphed me that the British expeditions have definitively confirmed the deflection of light by the Sun. Unfortunately, Maja has written me that you're not only in a lot of pain but that you also have gloomy thoughts. How I would like to keep you company again so that you're not left to ugly brooding. …"

The site was originally launched in 2003. Almost a decade later, a $500,000 grant from the Polonsky Foundation of London funded digitization of the 80,000 documents.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.