New Earth-like planets: How did astronomers find them?

Loading...

Since 2009, NASA's Kepler spacecraft has been sitting in space, pointing its telescope at a patch of the sky near the constellations Cygnus and Lyrae. Its field of view, a region of the Milky Way galaxy about the size of two open hands raised to the cosmos, contains roughly 160,000 stars. Scientists on the Kepler team are interested not in these stars themselves, but in the planets that may orbit them.

"The goal of the Kepler mission is to find planets like Earth in the habitable zones of their parent stars," said Guillermo Torres, a member of the Kepler team based at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. They are looking for Earth twins, because these are the likeliest candidates for worlds that could host extraterrestrial life.

To find these alien Earths, the Kepler team uses a technique called the "transit method." They scour the data collected by the Kepler telescope looking for slight drops in the intensity of light coming from any of the stars in its line of sight. About 90 percent of the time, these dips in brightness signify that a planet "has passed in front of its star, essentially eclipsing the light," Torres told Life's Little Mysteries.

Planets the size of Earth passing in front of a star typically cause it to dim by only one-hundredth of a percent — akin to the drop in brightness of a car's headlight when a fly crosses in front of it, the scientists say. To detect these faint and faraway eclipses, the Kepler telescope must be extremely sensitive and it must be stationed in space, away from the glare and turbulence of Earth's atmosphere.

Using the transit method, Kepler has detected 2,326 "candidate planets" so far, Torres said. Those are dips detected in starlight that are probably caused by passing planets, but for which other alternative explanations haven't yet been ruled out. [Could There Be Life on the New Earth-Size Planets?]

"The signals are an indication that something is crossing in front of the star and then you have to confirm it's a planet, not something else," he said. "Roughly 90 percent of the signals that Kepler detects are true planets. The other 10 percent of the cases are false positives. We're not happy with leaving the probability at 90 percent — we've set a higher bar — so, even though a priori we know a signal is 90-percent sure [to be a planet], we do more work."

To confirm that a candidate is a true exoplanet — a planet outside our solar system — the Kepler scientists use the world's largest ground-based telescopes to study the star in question, looking for alternative explanations for the transit signal. "One example is an eclipsing binary in the background of the star. There could be two stars behind the star [of interest] that are orbiting each other and eclipsing each other, but because they're in the background they're much fainter. So their light is diluted by the brighter star," he said.

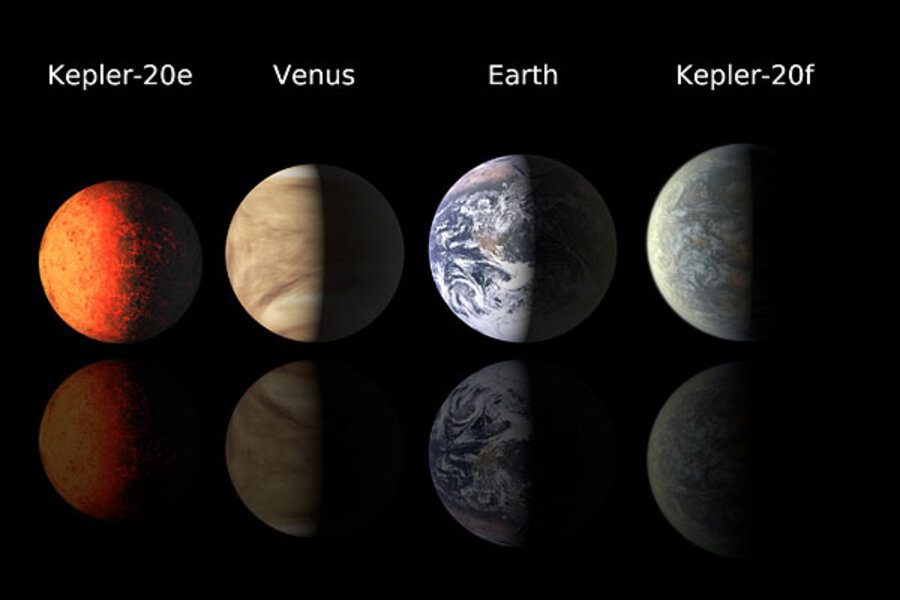

With today's (Dec. 20) announcement of five new confirmed exoplanets orbiting a star called Kepler-20 located 950 light-years away, including two that are Earth-size, the number of confirmed exoplanets has moved up to 33.

- A Field Guide to Alien Planets

- Stunning Photo of New Solar System Captured by Amateur Astronomer

- Will We Really Find Alien Life Within 20 Years?

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.