Jupiter's icy moon Europa rich in oxygen, study finds

Loading...

There may be enough oxygen in the waters of Jupiter's moon Europa to support millions of tons worth of fish, according to a new study. And while nobody is suggesting there might actually be fish on Europa, this finding suggests the Jovian satellite could be capable of supporting the kinds of life familiar to us here on Earth, if only in microbial form.

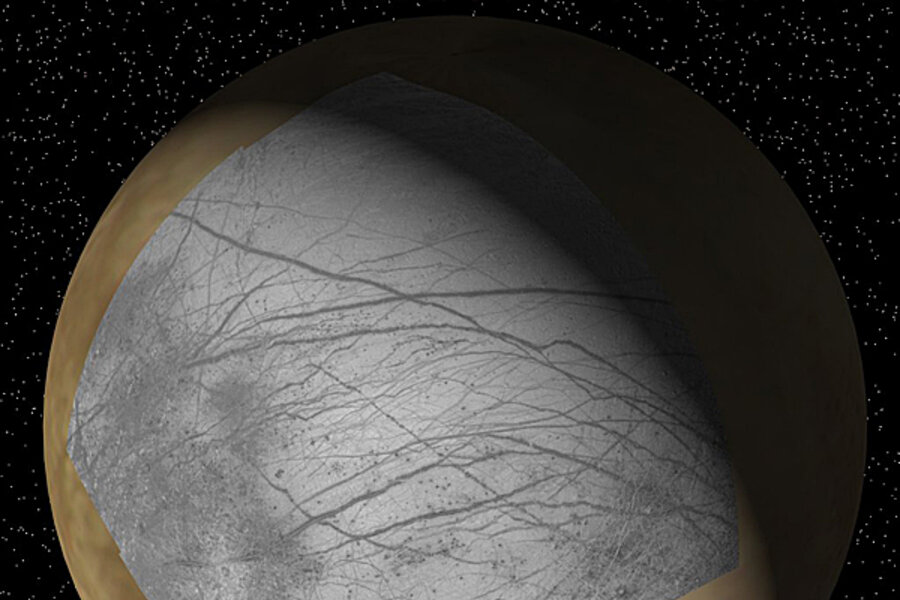

Europa, which is roughly the size of Earth's moon, is enveloped by a global ocean about 100 miles deep (160 km), with an icy crust that may be only a few miles thick. From what we know of Earth, where there is water, there is a chance at life, so for many years scientists have speculated that this Jovian moon could support extraterrestrials.

As we learned more about Jupiter's effect on its moons, the possibility for life on Europa grew even more likely. Studies showed the moon could have enough oxygen to support the kind of life we are most familiar with on Earth.

The ice on the surface, like all water, is made from hydrogen and oxygen, and the constant stream of radiation pouring in from Jupiter reacts with this ice to form free oxygen and other oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide. The reactivity of oxygen is key to generating the energy that helped multi-cellular life flourish on our planet.

Still, researchers had thought there was no effective method for delivering any of this oxygen-rich matter into Europa's ocean. Scientists had assumed the primary way for surface materials to migrate downward was from the impacts it would suffer from cosmic debris, which regularly bombards everything in our solar system. [Photos of Jupiter's moons.]

However, past calculations suggested that even after a few billion years, such "impact gardening" would never lead to an oxygenated layer more than some 33 feet (10 meters) deep into the ice shell, nowhere far enough down to reach the underlying ocean.

However, the new study suggests this oxygen-rich layer could be far thicker than before thought, potentially encompassing the entire crust. The key is looking at other ways to stir Europa's crust, explained researcher Richard Greenberg, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at Tucson.

The gravitational pull Europa experiences from Jupiter leads to tidal forces roughly 1,000 times stronger than what Earth feels from our moon, flexing and heating Europa and making it very active geologically. This could explain why its surface appears no older than 50 million years old — its surface underwent complete turnover in that time.

A major resurfacing process on Europa seems to be the formation of double ridges, which cover at least half of its surface. Tidal forces may be causing fresh ice from below — probably newly frozen ocean water — to push upward and over the surface, where it would slowly get oxygenated.

As ridges pile on top of ridges, older material gets buried, shoving this oxygen-rich matter downward. After one or two billion years, this process alone could spread oxidants throughout the entire crust, thus reaching the ocean, Greenberg calculated.

Other mechanisms could help stir Europa's crust also. Parts of the surface could partially melt from below, leading rafts of ice to break loose and tumble around before they froze back in place.

Roughly 40 percent of Europa's crust appears to be covered with the ensuing "chaotic terrain." Also, as matter comes up from below and widens cracks, the nearby surface crumples, burying some material. These extra processes could help push some oxidants downward, but it would still take at least two billion years or so before radiation loaded the entire crust with oxygen.

As ice on the base of this oxygenated crust melts, even with the most conservative assumptions, after only a half-million years oxidant levels in the ocean would reach the minimum oxygen concentration seen in Earth's oceans, which on Earth is enough to support small crustaceans, Greenberg found.

In only 12 million years, oxidant concentrations would reach the same saturation levels of Earth's oceans, enough to support our largest sea life. Given the cold temperatures and high pressures likely seen in Europa's ocean, it could actually take in more oxygen than Earth's oceans could before its water reached its saturation point.

"I was surprised at how much oxygen could get down there," Greenberg said.

One concern about all this oxygen was that it might actually do more harm than good. The extraordinary reactivity of oxygen could in principle disrupt the chemical processes that are thought to lead to the origin of life and that may have been an aspect of early life.

On Earth, life had more than a billion years to evolve, before oxygen became plentiful in the atmosphere, and that delay gave organisms plenty of time to develop genetic mechanisms and physical structures that allowed them to use oxygen, instead of being destroyed by it.

The delay of 1 to 2 billion years before oxygen in Europa's crust made its way into its ocean is roughly the same amount of time it took life on Earth to develop before oxygen became a problem, so life might have enough of a respite to develop on the Jovian moon. Assuming life on Europa respired at rates similar to fish on Earth, the continuous rate of oxygen delivery there could sustain roughly 3 million metric tons of life, Greenberg said.

One might not have to wait for a probe to land on Europa to detect any oxygen there. "Spectroscopy done by telescopes on Earth or in orbit can tell what substances are mixed into the ice," Greenberg said.

Greenberg detailed his findings May 6 in the journal Astrobiology.