3-D printing in schools: The next industrial revolution?

Loading...

| Boston

Though Leon McCarthy’s left arm ends at his wrist, today he can curl green plastic fingers around the handlebars on his bike.

Leon was born with a finger-less left hand, but doctors told his parents to hold off on a prosthetic until he was about his current age, 12. With prosthetic limbs costing upward of $30,000, Leon’s father, Paul McCarthy, looked to 3-D printing designs online to see if printing a hand would be an option.

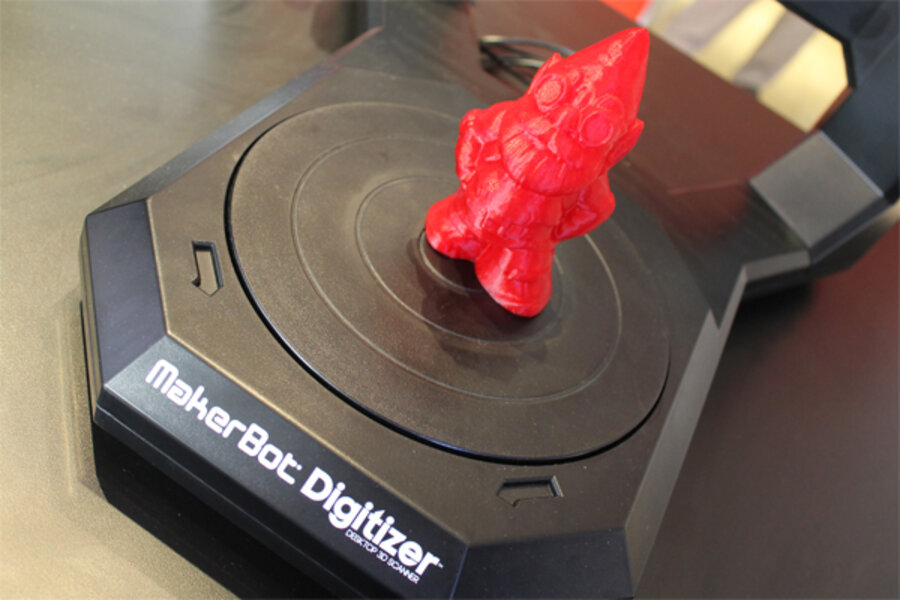

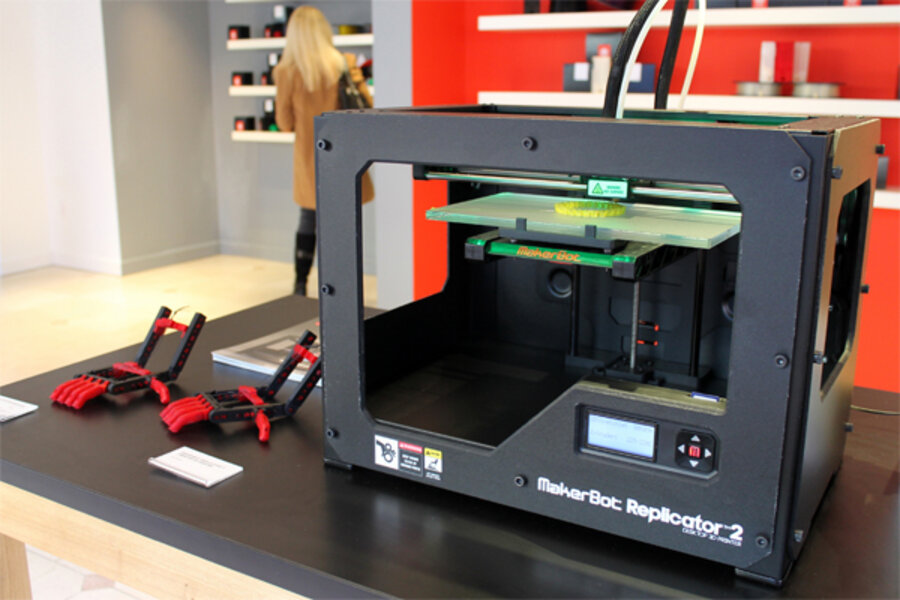

Coincidentally, Bill Sullivan, a science teacher and formerly Leon’s 5th grade teacher at Marblehead Community Charter School in Marblehead, Mass. had recently purchased a MakerBot 3-D printer through an education grant, and was looking for ways to integrate it into the classroom. He heard that Leon’s father had been looking into 3-D printing prosthetics. He decided to download the blueprint to a “robohand” and give it a try.

A little while later, Mr. McCarthy reached out to Mr. Sullivan asking if he would be interested in working together on developing a hand for Leon.

“I said, ‘Paul I just printed the hand. I would be psyched to do something,' ” Sullivan says.

3-D printing has skyrocketed in popularity in recent years, bolstered by open-source technology and the promise of making everything from rocket prototypes to car parts more widely available than ever before. Research firm Gartner predicts the number of 3-D printers shipped in 2013 will grow more than 49 percent over last year.

And now it is being lauded as "the next big thing" in education tech. 3-D printing company MakerBot recently announced MakerBot Academy, a crowd-funded initiative that aims to get a 3-D printer into every public school in America, and in as many as possible before December 31. MakerBot wants to kickstart a new industrial revolution in the United States by getting kids in front of the latest manufacturing technology. Similar initiatives have sprung up from NV Bots, a start-up from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and GADGETS3D, a company based in Hong Kong and Poland.

But with the struggles already facing school districts. is 3-D printing the best tech to get students excited about science and engineering?

Today, Leon has a functional robohand that he controls by using his wrist bones to put pressure on a lever system that clenches and releases his spindly plastic fingers, which he demonstrated at a MakerBot store opening in Boston on Thursday.

He, his father, and Sullivan are still experimenting with the design (a recent football catch snapped the fingers backward, though he was able to print new phalanges in a few minutes), and Leon and his father hope to lead a class devoted to 3-D printing and design at Marblehead Charter in hopes of creating more variations on the robohand to send to kids in need.

Sullivan is already using 3-D printing in lessons. He say being able to use Leon’s hand as an example of what kids can do with the technology has been a huge boost in helping kids feel capable of mastering new frontiers.

“Students are coming to me with question after question and idea after idea,” he says. “I attribute a great deal of this to the attention and the work that Leon, Paul, and myself have begun. They are seeing a connection to our experimentation and real life solutions.”

MakerBot CEO Bre Pettis has a similar vision for the introduction of 3-D printers in schools. At the opening of the Boston MakerBot store, he reminisced about his first steps into technology. In the early 1980s, his parents bought an Apple II computer, and soon after his school had Apple II computers as well.

“What we’re doing for students is what I got when I was a kid with that Apple II,” he says. “[We’re] giving kids the opportunity to get their hands on next-gen technology so they can solve the problems of tomorrow.”

Though putting a 3-D printer in every school is a noble idea, it could be tough to make it a reality for many schools. Currently only 39 percent of schools even have wireless Internet access, and digital inequalities tend to fall along socioeconomic lines. A recent study from the Pew Research Center found that teachers of the lowest income students are 35 percent more likely to say students’ access to digital technologies is a “major challenge” to bringing more digital tools into their classroom than those of the highest income students.

Nicolas Provenzano, a teacher in Grosse Pointe, Mich., and ed-tech blogger at The Nerdy Teacher, says districts set aside funding for different initiatives, and sometimes it can come down to what is needed most.

“[Some schools’] leaders have said 'we’re just going day to day, paycheck to paycheck here. We can’t afford a risk like that,' ” he says. “It’s really risk and reward.... You could get a 3-D printer or you could refurbish part of a lab.”

Because of that, grants and funding are key, which Sullivan even admitted was a challenge given the experimental nature of the technology. When he was asking for grant money, people questioned whether kids as young as 10 and 11 would have the know-how to use the new technology.

“It’s a hard thing to teach – the level of engineering classes [in middle school] are different from the levels [3-D printers] may seem more applicable for,” he says. “But when you put it in front of a kid that young, anything is possible.”

This is the first year that Sullivan is using the 3-D printer in the classroom, so the work they’ve done so far has been more experimental, he says. Students have worked on everything from trusses to test structural design to levers and pulleys. And it doesn’t always work. Sullivan puts botched printed products on display as a reminder to students that the printing is only part of the equation – good design, structure, and solid ideas are key to making sure the end result is effective.

However, he says just offering the option to explore 3-D printing has oriented his students toward new technology.

“We’re trying to become a 21st century school – what skills are they going to need?” he says. “Just having it creates a buzz. They are psyched that it is a shiny new thing. They do research on their own.... They’re not just consumers of electronics.”