When character counts in choosing a president

Loading...

| Claremont, Calif.

Americans have a good idea of how Barack Obama would do in the 2013-17 term: Just look at what he's done since 2009.

Appraising his major rivals is trickier. Should voters weigh the character of candidates or focus only on their positions? A high-minded person might say that we should just look at policy, averting our eyes from the grubby details of personality.

But if we want to ponder how a candidate would fare in office, this approach won't take us very far. Read my lips: Candidates will break their promises.

More important, they cannot anticipate all of the issues that will emerge during the next presidential term. Political scientist Amy Black points out that terrorism scarcely came up during the 2000 campaign, even though it would become the central national concern a year later.

Character counts, but let's be clear on what "character" means. When journalists use the term, they are often referring to politicians' personal lives. This kind of "character issue" can be relevant if private sins taint public behavior, as they arguably did in the Lewinsky affair, when President Clinton gave misleading testimony in federal court.

Such cases are the exception, however. Usually there is no clear link between home life and political life. Franklin D. Roosevelt was an unfaithful husband and a neglectful father, but he was still a great president.

For the purpose of choosing a chief executive, it is more important to think about public character. How have candidates conducted themselves in office, in business, or on the campaign trail? Have they shown the cardinal virtues of courage, self-control, wisdom, and justice?

Political courage is the willingness to risk one's electoral future for the sake of the greater good. In "Profiles in Courage," John F. Kennedy wrote about senators who took unpopular stands, and some of them went down to defeat.

Newt Gingrich has displayed such courage from time to time. During the 1980s and '90s, his efforts to elect a GOP House majority put him high on the Democrats' target list. He kept at it, even though they nearly denied him reelection more than once.

Nevertheless, his courage took plenty of vacations when it came to policy convictions: Expedience led him to embrace trade protectionism and pork-barrel spending.

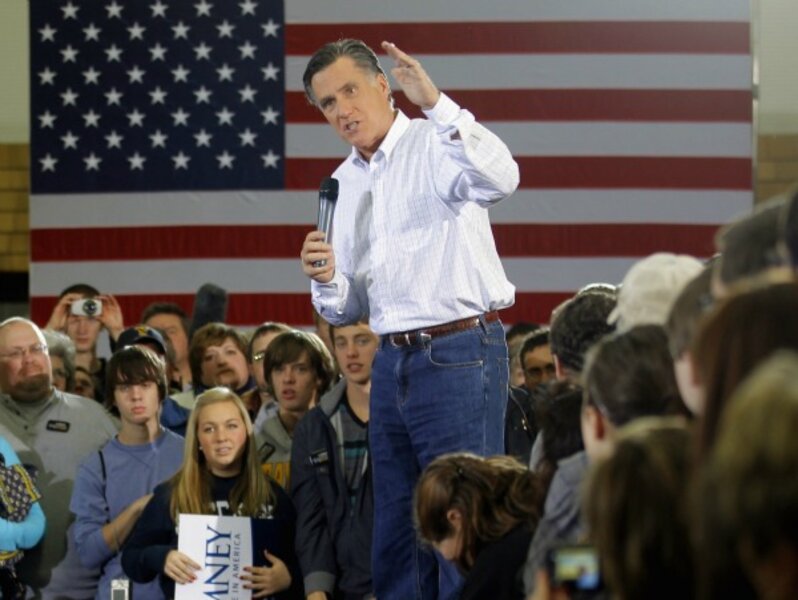

As for another major GOP candidate, Mitt Romney's would be a short chapter in "Profiles in Courage." When he was running for senator and governor in liberal Massachusetts, he cast himself as a pro-choice moderate. When he launched his first bid for the GOP nomination for president in 2007, he became more conservative. His conversion may well be genuine, and a President Romney might actually run political risks to uphold conservative principles. But his career to date offers little precedent.

What Mr. Romney has in abundance is self-control. Thanks to his capacity for concentration and discipline, he went from earning top grades as a student to making top dollar as an executive. Everything about him – from his economic plan to his hairline – is methodically arranged. His campaign book is titled "No Apology," but a more fitting title would be "No Surprises."

If Romney is a model of self-control, then Mr. Gingrich showcases something else. If you look in a dictionary for the word "impulsive," you may find his picture.

MSNBC newscaster Joe Scarborough, who served with Gingrich in the House, recalls a colleague who said, "Newt, you can tell us what is going to happen in America 50 years from now but you never seem to have any idea what we'll be doing on the House floor next week." Earlier this year, his flighty behavior prompted most of his campaign staff to quit.

Practical wisdom, or prudence, is another problematic area for the former speaker. This virtue encompasses many things, especially the ability to make distinctions. The wise person can tell what is important from what is merely interesting, and can sense when normal risk-taking shades into recklessness.

Gingrich is a font of ideas, but many of them – such as lunar mines and space mirrors – are impractical. Bob Dole once said, "You hear Gingrich's staff has these five file cabinets, four big ones and this little tiny one. No. 1 is 'Newt's ideas.' No. 2, 'Newt's ideas.' No. 3, No. 4, 'Newt's ideas.' The little one is 'Newt's Good Ideas.' "

The former House speaker is a case study of the difference between intelligence and practical wisdom. As Tom Stoppard once wrote, "You can persuade a man to believe almost anything provided he is clever enough, but it is much more difficult to persuade someone less clever."

Romney is less clever and more prudent than Gingrich. A Romney administration would probably avoid unworkable proposals. The defect of this virtue could be a lack of creativity: There wouldn't be many wild ideas, but there might not be many innovative ones either.

Justice is about giving everyone what he or she is due. When public figures practice justice, they keep commitments to others and honor their obligations to the offices they hold.

Gingrich has had trouble in this area as well. As speaker, he became notorious among other lawmakers for pie-crust promises: easily made, easily broken. Carelessness about his ethical duties triggered an investigation that ended in his payment of a $300,000 settlement to the House ethics committee.

Romney's career has been free of such missteps, but his critics lodge another kind of charge: He made business decisions that cost many ordinary workers their jobs. His supporters reply that the layoffs were unavoidable and that he created many jobs.

The careers of Romney and Gingrich will continue to provoke debate and discussion – as well they should. We are not just picking a bundle of issue statements; we're hiring an individual to do complicated work under unpredictable conditions.

And since our very lives may depend on that person's performance, we're entitled to ask some probing questions. As journalist Jeff Greenfield once said, is there anything you don't want to know about someone who's asking you for the power to blow up the world?

John J. Pitney Jr. is the Roy P. Crocker professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California and coauthor of "American Government and Politics: Deliberation, Democracy, and Citizenship."