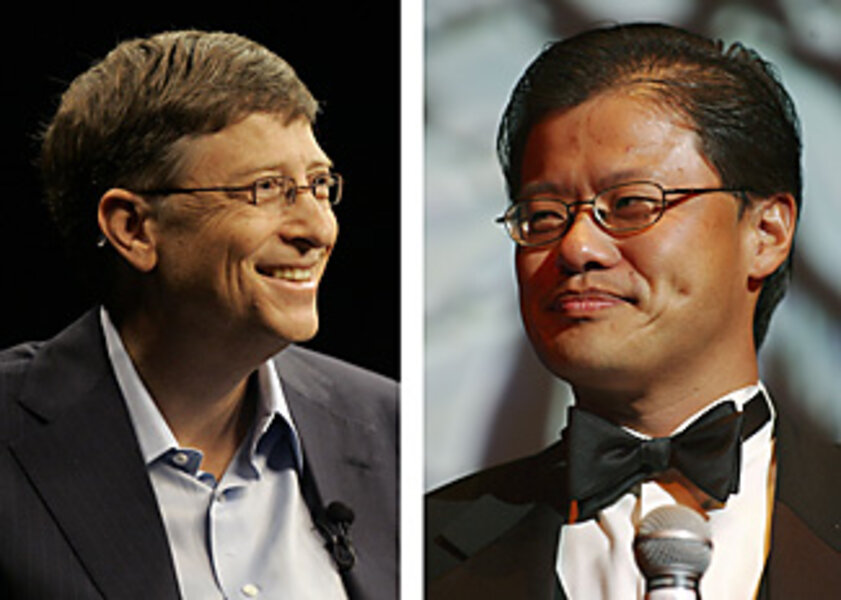

A Microsoft-Yahoo! merger: good for the Internet?

Loading...

| Oakland, Calif.

The more people who look for deals on eBay, or create a Facebook page, or post jobs on Craigslist, the more valuable these sites are for subsequent users. It's called a network effect, and it's behind the tendency in a lot of high-tech industries to consolidate into one or two dominant companies.

It's also the backdrop of the fight between Microsoft and Google this week over control of mutual rival Yahoo!. Microsoft made a $44.6 billion bid Friday for the struggling Internet leader, after failing to persuade government regulators last year to stop Google's merger with ad serving company DoubleClick. Microsoft argued at the time that it could not catch up to Google in delivering certain forms of online advertising because of network effects.

Now Google has reacted to Microsoft's bid by leveling the same cry of creeping monopoly, arguing that a Microsoft- Yahoo! combination would dominate in e-mail, instant messaging, and Web portals. "Could Microsoft now attempt to exert the same sort of inappropriate and illegal influence over the Internet that it did with the PC?" reads Google's press statement.

Above all, the acquisition would leave Google and Microsoft as the only major conduits connecting advertisers and online publishers. Just how much that bothers certain analysts depends somewhat on whether they think network effects would solidify an unhealthy dominance.

"Search is not really a business that has those network-effect characteristics," argues Jonathan Weber, former editor in chief of The Industry Standard magazine. Much online advertising is currently tied to the results returned by search engines, which has given Google a huge lead – for now.

Mr. Weber recalls an Industry Standard conference in 1999 where insiders ridiculed Google, then a start-up. Their reaction: Why would we need another search engine? We already have Yahoo! and Inktomi and Infoseek and AltaVista. Google's answer: We think we're a better search engine.

The moral of the story, says Weber, is that the moment a better search technology comes along, Google – or a Microsoft-Yahoo! combo – could tumble.

An edge in contextual ads

Google currently handles 56 percent of all US searches, versus 32 percent for Microsoft and Yahoo combined, according to data from Nielsen, an audience metrics firm.

Google's lead in another form of online advertising known as contextual advertising is similarly not fixed in stone, say some experts. Contextual ads are placed on the fly by Google onto third-party webpages whose content matches keywords given by advertisers. So, air travel companies, for instance, might place ads for keywords like "honeymoon" or "vacation," and Google will find pages that seem focused on those topics and place the ads there.

Google currently has a strong inventory of websites willing to receive the ads for a cut of the money. But that network could be poached by Microsoft with an offer of more revenue per click, says Samir Patel, CEO of SearchForce, a software company based in San Mateo, Calif., that helps advertisers calculate the effectiveness of online ads.

"Each employee of these two mega companies [Microsoft and Google] is going to be focused on search and online advertising," says Mr. Patel, who argues that a Microsoft-Yahoo! union would spur on Google by giving the company more serious competition. "As long as there are at least two strong companies, they will have to be competitive in terms of paying off the publishers. It will keep themselves in check."

Dangers of only two ad 'pipelines'

Others, though, warn that Microsoft and Google will become the sole pipes through which advertising dollars flow to Web publishers. They are becoming ad serving companies, a sort of middleman between advertisers and publishers, that have enormous power because of their ability to help online advertisers target very specific demographics and content areas.

"The middleman has much more power over the media firms than ever," says Joseph Turow, professor of communication at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. "Those who control the advertising [also] structurally control the content."

It is argued that, so far, there has been at least one positive structural impact: Obscure writers and publishers, once overlooked by advertisers, now stand a greater likelihood of getting a small cut through contextual advertising.

But having only two major ad serving companies – both of which can target ad dollars with great precision to websites dedicated to topics vital to advertisers – could end up curtailing the kinds of content people produce.

"You are literally creating a second-by-second Nielsen system, where you are going to know precisely what customers are interested in and be able to immediately redirect your advertising based on that," says Jeff Chester, head of the Center for Digital Democracy, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving an open Internet that serves the public interest. "Google becomes everybody's not-so-silent partner because it's such an important part of their revenue base. Google can have an automatic influence over the content."

The temptation to let ratings determine content isn't a new phenomenon in media, notes Weber, now publisher for a Rocky Mountain regional news service called NewWest.net.

While consolidation has created a few online advertising giants, he says, small but successful independent advertising networks have also emerged. Such networks, Federated Media among them, pull together a number of independent publishers who can collectively achieve the critical mass needed to draw advertiser attention.