How a book by a White House insider made waves ... in 1868

Loading...

Exactly 150 years ago, another insider account captivated the nation by exposing the secret inner workings of the White House. But seamstress Elizabeth "Lizzy" Keckley, a former slave who became Mary Todd Lincoln's dressmaker, didn't spout gossip or uncover infighting.

In fact, her memoir about the Lincoln White House only reveals a few juicy tidbits, making it less of a tell-all then a tell-some, a far cry from books like "Fire and Fury" by Michael Wolff, "All the President's Men" by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and the memoir of Warren G. Harding's mistress.

Still, 1868's "Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House," must have astounded readers with its moving depictions of private moments. The book still has the power to touch hearts today, with its stories of the president's tenderness, the death of the young Lincoln son Willie, and Mrs. Lincoln's perceptive views about the Union Army's generals.

Mrs. Lincoln, who felt deeply hurt, added the book's publication to the long list of her life's miseries. She never again talked to Keckley, once perhaps her closest confidante.

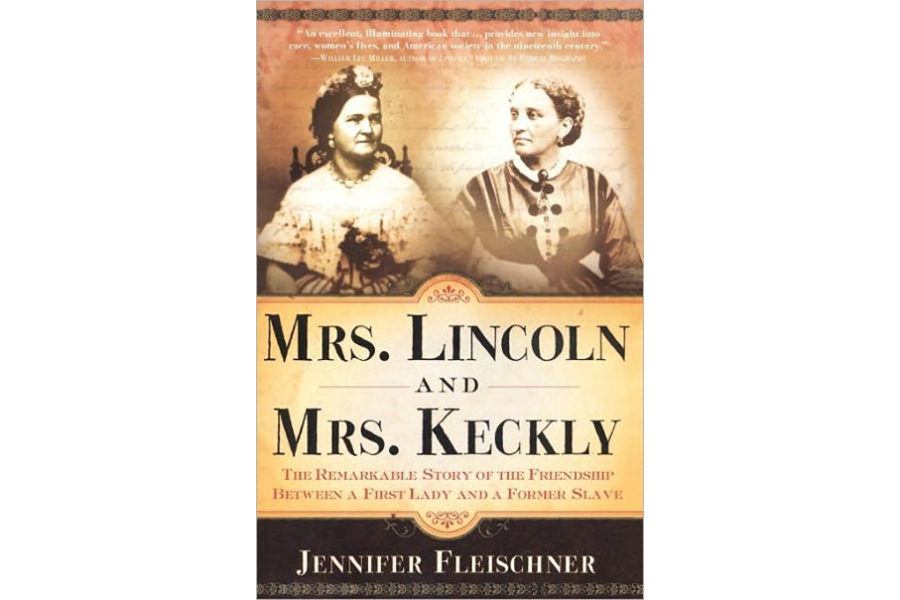

Jennifer Fleischner, the chair of the English department at New York's Adelphi University, captures the women's unusual relationship in her 2003 book Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave. (There's disagreement over whether the memoir author's last name is properly spelled Keckley or Keckly; Fleischner prefers Keckly.)

I asked Fleischner about the roots of "Behind the Scenes," the reaction to its extraordinary publication, and the parts that touch her the most.

Q: What does this memoir tell us about Abraham Lincoln?

It's an eyewitness account from someone who was hired on the day of Lincoln's inauguration. She combed Lincoln's hair, and she could walk by and see him reading the Bible or mumbling to himself while preparing a speech shortly before his death.

Frederick Douglass said Lincoln treated with him respect, and you can feel that Keckley felt this connection, too.

We also learn a lot about personal details like the night of Willie's death. She saw Lincoln weeping over the body. ["I never saw a man so bowed down with grief...," Keckley wrote. "His grief unnerved him... I did not dream that his rugged nature could be so moved."]

And we learn about Lincoln trying to manage his wife's despair and distress around Willie's death, her nervous breakdowns and depressions.

Q: What was her relationship with Mary like?

Lizzy was an independent businesswoman, the top dressmaker in Washington D.C. Mary really needed her to make her way, and they collaborated on her wardrobe.

Mary had strong ideas about fashion, though Lizzy was also known for telling white women who employed her what they ought to wear. She could "steer" Mary in dress and even behavior.

Q: Despite its title, the very readable "Behind the Scenes" is much more than an insider view of life in the White House. What else does it portray?

The first quarter is about her life as a slave. There was a long tradition of these slave narratives – eyewitness accounts of the horrors of slavery – before the end of the Civil War and emancipation. She's also writing an up-from-slavery book, a genre you see a lot of after the Civil War.

But the war is over, and an exposé of slavery is not going to sell the book. What's going to sell is seeing inside the White House. There wasn't a tradition of that then.

Q: What was Keckley trying to accomplish by writing about the Lincolns?

She is revealing things, but Keckley thought of herself as defending Mary's character and explaining its peculiarities, her behaviors since her husband's death and her need for money.

She writes about Mary's explanation about why she had to buy 300 pairs of gloves: They were going to be her piggy bank [goods that could be sold if needed].

Q: Keckley writes that "if I have betrayed confidence... It has been to place Mrs. Lincoln in a better light before the world." What did the former first lady think?

Mary saw it as a betrayal. She felt betrayed and exposed and angry that personal things were talked about.

Q: How did critics of the book react?

Keckley was black, a former slave, a woman. The public thought: Look what happens when you liberate and educate people. What family is going to want servants if servants can do this?

Q: What does this memoir mean to you?

What touches me about the book is not the Lincolns. It's Lizzy, this woman who was born into slavery and survived the brutality and dehumanization intact with a sense of herself and her worth. She survives with wit and humor and hope and ambition.