'American Fire' spotlights a troubling rural arson spree solved by old-fashioned legwork

Loading...

A century ago, Virginia's Accomack County was one of the wealthiest rural regions in the entire United States. Then it drifted. Farming dried up, and the glitzy resort hotel shut down. Now this colonial-era outpost on a peninsula between Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean is one of Virginia's poorest counties.

In 2012, somebody torched an abandoned house. Then another building went up in flames. And another. By the time it was all over, investigators counted almost 80 arson-set fires, a string of blazes that criss-crossed the county and nipped at its northern border with Maryland. No one would be killed, but the fires left this red county in a blue state both focused and frightened.

Who did it? A troubled couple in love. He was a car mechanic and volunteer firefighter, she managed a little women's clothes shop, and they lived ordinary blue-collar lives. Then, "to say the least," says Washington Post reporter Monica Hesse, "something went deeply wrong."

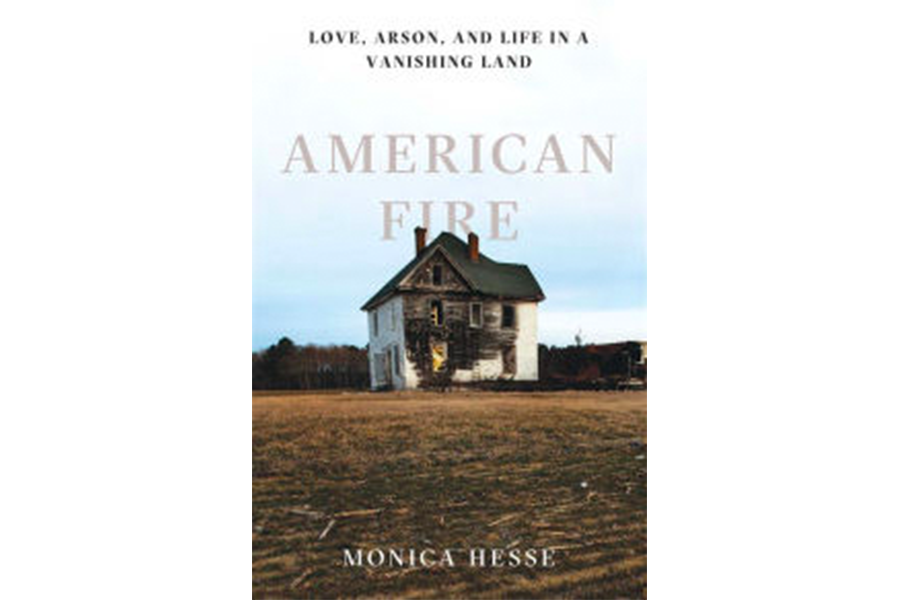

She tells their story in American Fire: Love, Arson, and Life in a Vanishing Land, one of the year's best and most unusual true-crime books. In an interview, Hesse describes the world she found on the Eastern Shore and the wider meaning of this fascinatingly bizarre tale.

Q: What makes this an American story, as your title suggests?

I started off thinking these fires could have only happened in Accomack, that this place was primed for these crimes. But then I began to understand the things that led up to them – the aging of rural populations, the brain drain that some rural counties experience, and people having to make the shift from manufacturing or agriculture to other jobs.

This could have been Wyoming or the rural Midwest, where I'm from. It could have been in a lot of places.

For me, it became a story about America in that larger way, and also about America through the love story at the center of it. The people arrested were not trying to have some grand, epic, soft-focus love story. They were just trying to grill on their patio, drink root beer, take care of their kids, and not go underwater with their house debt.

It seems very American to try to make it. But, to say the least, something went deeply wrong.

Q: What is Accomack County like?

It feels like you are driving through decades of history. The county has changed so much, and there are still all of these ghosts of what it used to be.

There's lot of land, and a lot of it is rural – old farmhouses, feed silos and barns that aren't needed as much in the modern world. Streets become pathways and go through woods where you can come across a shack that no has seen for 100 years. These are all signposts for the county and what it's been through in its 300-year history.

Q: What about the county made it possible for the arsonists to go uncaptured for so long?

At first, the outside experts thought the arsonists must be daring. But when they got there, they realized that you could light things on fire for days and days and not get caught.

A lot of Accomack County just feels like blackness. It is dark, there are no street lights and often no street names. You can go miles and pass no one. There's no way to have eyewitnesses or police stationed at every corner.

Q: Technology drew people together even in this remote place. Residents went online to compare notes, make accusations. and even set up stakeouts themselves. What did you make of that part of the story?

In some ways, no place is truly isolated. This is not a backwater. Everybody has Facebook, people are keeping up with the latest memes, doing the Harlem Shake, playing World of Warcraft.

If you ever want to see a microcosm of the human experience, look at the Facebook groups with accusations flying around and talk about how we're going to catch him and how this is all happening because of X, Y, and Z. The whole town can have these discussions online.

Q: But it didn't take high tech or profilers to solve this case, although they were all put into action, right?

Accomack is a place where everyone knows who belongs and who doesn't, where a handful of names go back generations and generations to the 1600s. The sheriffs and deputies, whose own names go way back, know where these abandoned houses are, and they said they'd solve the case through old-fashioned legwork.

The case shows the value of staying in place, of getting to know your area really well.

Q: What's the legacy of this story?

As long as the people who are living now are still alive, they will remember this. Everyone has a story to tell, whether it's their neighbor's shed that burned down, or they searched for the arsonist, or people thought they were the arsonist. Everybody had a relationship with this event that transformed this place.

That's the story I wanted to tell: what happens to a county when it's burning down around you.