Authors petition UN for Digital Bill of Rights

Loading...

From librarians protesting the Patriot Act to writers speaking out against government surveillance, the literary community has tended to be a vocal defender of civil liberties.

Responding to recent widespread state spying, more than 500 authors from around the world – including five Nobel Prize winners – have signed a petition asking the United Nations for a Digital Bill of Rights.

The petition comes a day after leaders of major tech companies, including Google, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, LinkedIn, Yahoo, and AOL, published an open letter asking Congress and the President to take steps to restrict government surveillance.

The authors’ petition warns that state spying undermines democracy and demands restrictions on domestic surveillance via an international charter.

“A person under surveillance is no longer free; a society under surveillance is no longer a democracy. To maintain any validity, our democratic rights must apply in virtual as in real space,” the statement reads. It continues, "WE DEMAND THE RIGHT for all people to determine, as democratic citizens, to what extent their personal data may be legally collected, stored and processed, and by whom; to obtain information on where their data is stored and how it is being used; to obtain the deletion of their data if it has been illegally collected and stored.”

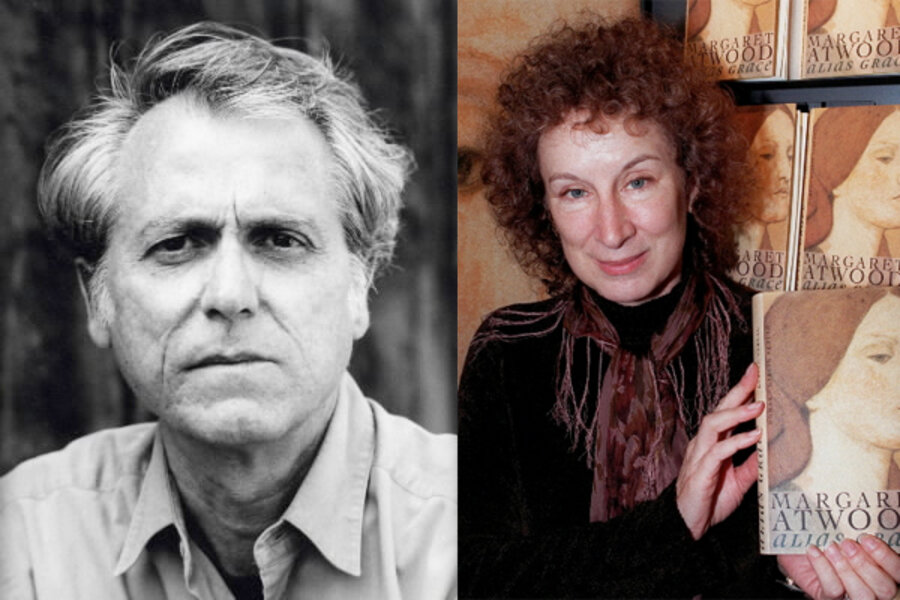

The author signatories hail from 81 different countries around the world and include such notable names as Margaret Atwood, Ian McEwan, Don DeLillo, Orhan Pamuk, Arundhati Roy, Gunter Grass, Martin Amis, and Tom Stoppard.

People should have a right to remain unobserved in their communications, the petition states, adding, “This fundamental human right has been rendered null and void through abuse of technological developments by states and corporations for mass surveillance purposes.”

The petition also states that surveillance compromises freedom of thought and opinion and treats every citizen as a potential suspect.

It represents a growing trend of public opposition to government spying of citizens by the National Security Agency. Brazil cancelled a US state dinner in protest; German leader Angela Merkel chastised President Obama about it, calling it a “grave breach of trust”; and most recently, major tech firms have united against it.

As we reported in an earlier post on writers expressing concern about government surveillance, in June 2013, former CIA employee and NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents detailing National Security Agency surveillance on American citizens and media organizations. It is now known that the NSA collected phone records of millions of Verizon, AT&T and Sprint subscribers and that NSA analysts can search through vast databases of emails, online chats, and browsing histories of millions of individuals with no prior authorization.

That knowledge has had the chilling effect of self-censorship on some writers, according to November 2013 PEN survey.

“Writers are kind of the canary in the coal mine in that they depend on free expression for their craft and livelihood," PEN’s executive director Suzanne Nossel told the New York Times in a November 2013 interview.

That’s why we’re not surprised that folks in the literary community are deeply disturbed by reports of government spying – and deeply committed to fighting it.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.