In Brazil's prisons, inmates shorten sentences by reading

Loading...

Now here’s a novel idea. One way to solve prison overcrowding, promote literacy, and empower inmates, in one fell swoop? Offer inmates the chance to shorten their sentences by reading.

That’s right, Brazil’s government recently rolled out a new program, Redemption through Reading, that allows inmates to shave four days off their sentence for every book they read, with a maximum of 48 days off their sentence per year, Reuters reported Monday. The program will be extended to certain prisoners in four federal prisons in Brazil holding some of the country’s most notorious criminals.

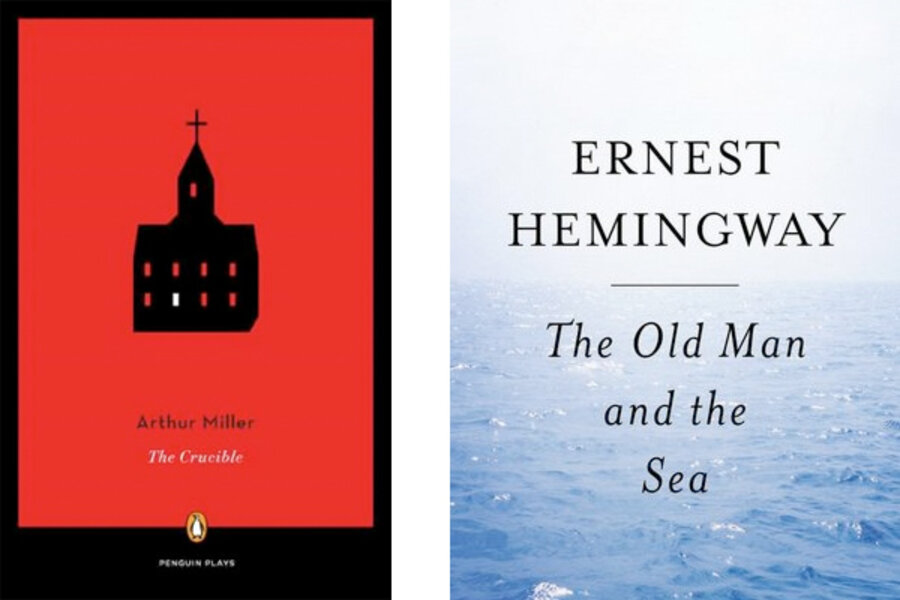

According to Reuters, a special panel will determine which inmates are eligible to participate. Those chosen can choose from works of literature, philosophy, science, or the classics, reading up to 12 books a year. Flashback from grade school: they’ll have four weeks to read each book and write an essay that must “make correct use of paragraphs, be free of corrections, use margins, and legible joined-up writing,” according to a notice published Monday in Brazil’s official gazette.

“A person can leave prison more enlightened and with an enlarged vision of the world,” Sao Paulo lawyer Andre Kehdi, who directs a book donation project for prisons, told Reuters.

And according to the New York Daily News, the trend of shortening sentences through reading is nothing new. As recently as last month, judges, like US District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers in the Bay Area, handed out similar stipulations to inmates eager to shorten their sentences.

Nonetheless we’ve got to admit, as bibliophiles, as much as we like the idea, we aren’t convinced. How does reading help rehabilitate prisoners? Is this the best way to offer inmates a sentence-shortening incentive? Is it truly constructive? And as we learned in fifth grade, writing a book report is no guarantee that one has really finished a book. How do we ensure that the prisoners are really doing the reading thoroughly and completely?

Questions aside, we are intrigued by the idea and eager to see how it plays out in Brazil. We’ll keep you posted.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.