Roger Rosenblatt: How do you teach writing?

Loading...

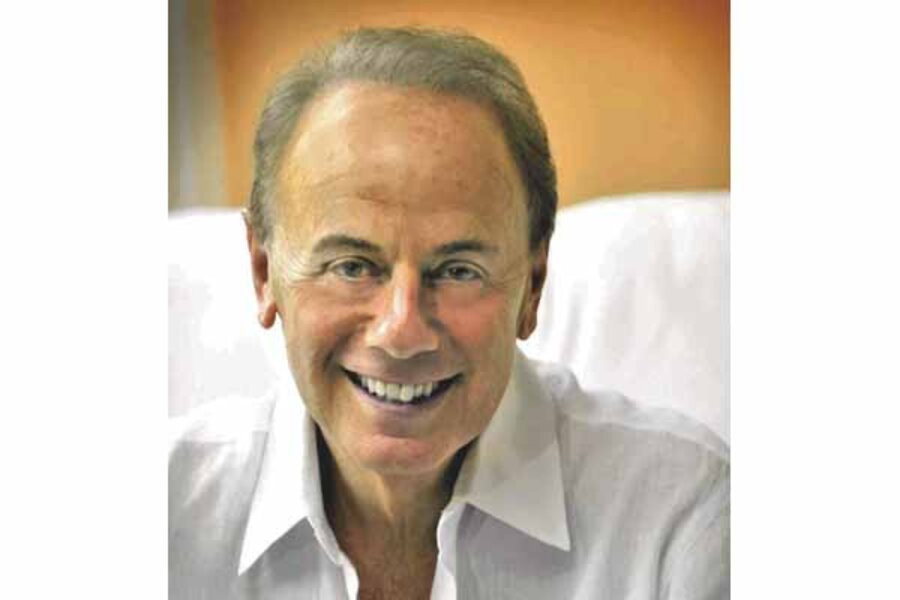

Roger Rosenblatt is known as a writer. Very well known, in fact. His essays for Time and PBS have earned him two George Polk awards, a Peabody, and an Emmy. He is also the author of six plays and 14 books. But Rosenblatt has another less highly publicized career. He is also a teacher of writing at Stony Brook University in Southampton, N.Y. His new book "Unless It Moves the Human Heart" reports on one semester in his "Writing Everything" class. I recently had the chance to ask Rosenblatt about his book and what it means to be a teacher of writing.

So many “experts” insist that writing cannot be taught. But you believe that it can. What gave you that conviction?

One idea started a number of others. [It began with] my need to break my students of the habit of apologizing for what they were writing. Whether it was a story or a novel or a novella or an essay they tended to start with either the apologetic desire to tell you what they were going to write about or by hesitating before they launched into it. This involves two mistakes: (a) Nobody’s interested in having you tell them what the subject is going to be. And (b) by the time they get into it they’ve already developed a kind of stutter step that makes their writing feel kind of clogged and unnatural.

So I thought to myself: “How do I get through this throat clearing?” And I started to bring them various things to see or smell or touch or taste that would go right to their senses and cut out any process of intellectualizing. If I played jazz for them it would recall something in their lives. If I gave them a flower to smell it would recall something in their lives. In one instance, I closed the door and the sound of the closing door would be another sensory stimulus. Once I did it, then I saw that they launched into their work with an entirely different vocabulary and an entirely different zest and a feeling of themselves. Then I began to think, there are other things one can really do to teach one to write in a more sophisticated way. And I started to pay attention to such things. I started paying attention to [things like] the power of the noun, to using anticipation over surprise, imagination over invention, things like this that are not exactly nuts and bolts of writing but they are related and they work in the service of a larger goal.

I began to see the results and once I saw the results I thought that I must be doing something right and I become confident that I was actually teaching a bit about writing.

Who taught you to write?

I went to the the Friends Seminary in New York, which was a dreadful school largely, except for one fellow named Jon Beck Shank. He was a Mormon who had come out of the army, went to Yale, and was very interested in theater. He gave us Canada Mints to taste and said, “Taste this and write down what it tastes like,” so we would learn to write metaphor and simile. He had us read poetry, a great deal of poetry so as to appreciate original language. When we studied Shakespeare he had us build a model of the Globe Theater. He just did things that no other teacher would have thought of doing to get into our minds so that we would begin to understand that writing was something that was important to our lives. I was very very lucky to have had him. He meant the world to me.

At Harvard there was this fellow John Kelleher who didn’t teach writing but he was so smart. He was a professor of Irish literature and I got my degree in Irish literature. I didn’t know a thing about Irish literature but I just knew that this was the man I wanted to affix myself too. He wasn’t a writing teacher but he was a teacher in a larger way.

And finally Robert Lowell, the poet, with whom I took a poetry seminar. He was very severe and the opposite of the kind of teacher that I became. But it was something, knowing at that time, in the 1960s, that one was being taught by one of the best poets in America. It gave a taste of the writing life.

What are some common stumbling blocks to good writing?

One of the simpler ones is that you have to find a different way to say “say.” If someone says something in one paragraph, then he has to "aver" it in the next, then he has to "declare" it, then he has to "shout" it. What it does is make the reader start to focus on these various ways to say “say” when what you want to focus on is what is said.

Also [my students] don’t know that they can just say something once instead of saying it 100 times. They only need to say it once – and then just leave it alone.

Another is over-decorating. If you need three adjectives to describe something, then you’ve probably chosen the wrong something. If you chose the right word, the right noun, you don’t need to overburden it with anything that you think will make it more pretty. It will stand up on its own.

What have your students taught you?

That they need me. They need me and my ilk. They need teachers who value them and their lives. Because writing is a validation of their lives and they know it. Whether they’re writing poetry, essays, or stories, it doesn’t matter. Every writing teacher gives the subliminal message, every time they teach: "Your life counts for something." In no other subject that I know of is that message given.

Do you enjoy life as a writer?

Yes. I think there must be something wrong with me as a writer. Because all my friends who are writers find reasons to hate everything about their day. But I just love writing. I love starting the day with language and seeing if I can make something of it.

Most of your students will never publish a book. Yet you encourage them to write. Why?

You’re probably right, over 50 percent of my students will not publish a book. Although most of my students – about 80 percent – deserve to be published, whether they are or not.

But never would I discourage them from this mad pursuit. The only reason I can see for them to pursue art is for its own sake. They will receive as much satisfaction out of that pursuit as they will out of publication and in some cases more.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor's book editor.