'Basketball' is a fast-break compilation that goes from from the beginning to Stephen Curry

Loading...

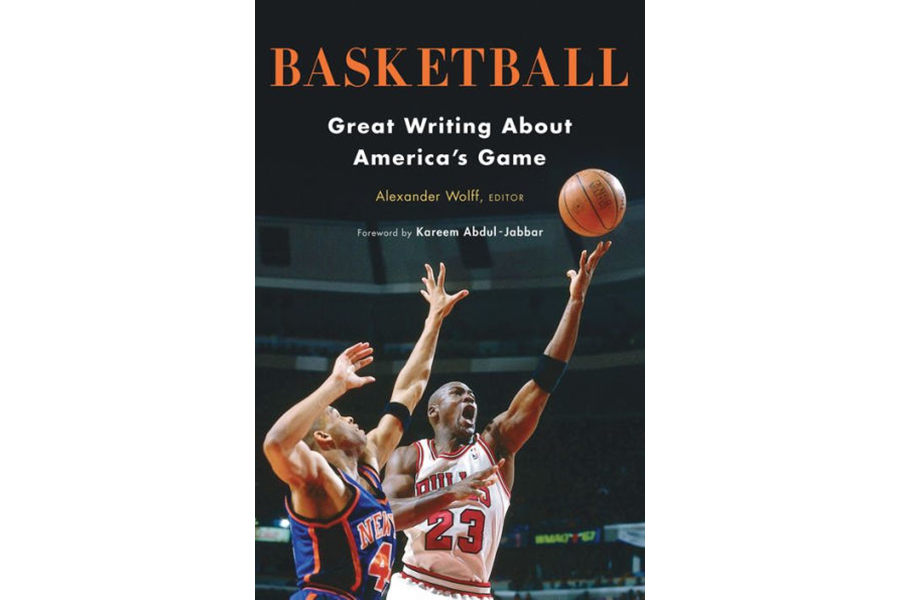

This month brings the climax of the college basketball season – March Madness, remember? – followed in April by the start of the two-month marathon that is the NBA playoffs. And if that’s still not enough roundball, Basketball: Great Writing About America's Game, a new Library of America collection of the best basketball writing, offers an embarrassment of riches to restore your spirits once your bracket goes bust.

Longtime Sports Illustrated writer and contributor Alexander Wolff curated the collection and he’s done it so well that this reader has but one quibble: Why leave out an excerpt from John Feinstein’s “A Season on the Brink,” the 1986 bestseller chronicling a year inside the Indiana Hoosiers program with coach Bobby Knight?

That complaint aside, Wolff has put together a fast-break compilation that takes the reader literally from the beginning – in a sliver of memoir from James Naismith on how he invented the game in 1891 – to the present-day reign of Stephen Curry and the Golden State Warriors.

Curry, writes Rowan Ricardo Phillips, has taken pure shooting into the realm of artistry.

Anyone who’s ever watched Curry knows this to be true, but it’s much more fun to think about in Phillips’ words: “He’s to the point where he’s putting the ball up like he’s getting rid of a bomb. He sometimes looks like he’s just throwing the ball up. Then there are the finger rolls, scoop shots and teardrops with either hand. He’s rising up from twenty-five feet out and skedaddling back to the other end of the court as soon as the ball leaves his hand.”

Yes, that. (Phillips, by the way, is an All-Star himself, toggling between a renowned career in poetry and dabbling in sportswriting at The Paris Review.)

Besides Curry, many of the game’s top players and teams from all eras are featured in these pages, including Bob Cousy, Bill Russell, Pete Maravich, Michael Jordan and the six-time champion Chicago Bulls of the 1990s, Magic Johnson’s Olympic Dream Team and so on. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar may be the ultimate MVP: A Hall of Famer on the court who also contributes a smart foreword and a thoughtful excerpt from his account of teaching the game on a Native American reservation.

The roster of writers is every bit as impressive, from Frank Deford’s for-the-ages profile of Indiana coach Knight (“The Rabbit Hunter”), which probably led to Feinstein’s ouster to preserve diversity of subjects, to Jimmy Breslin on Marquette coach Al McGuire’s wise-guy street hustle and heart and continuing with David Halberstam’s portrait of the late-'70s Portland Trail Blazers. Contemporary selections include ESPN’s Zach Lowe, who takes a break here from his incisive and rigorous analytical approach to reflect on losing his fandom, and Michael Lewis, who explores and explains the often-overlooked Shane Battier, who played 13 NBA seasons and invariably improved his team’s performance with few people knowing how he did it. Lewis’ explanation, mined, in part, from Houston Rockets executive Daryl Morey, provides a clinic on journalism that doesn’t just tell what happened, but why.

It would be impossible to assemble a greatest-hits album of basketball chronicles and exclude New Yorker writer John McPhee’s profile of Bill Bradley during his days starring at Princeton. Younger readers may not know Bradley’s college hoops heroics — or what followed. He went on to play for the New York Knicks in the NBA and then served three terms as a U.S. senator from New Jersey before running for president in 2000. Pete Axthelm reveals the opposite end of the spectrum in “The City Game,” a gritty glimpse of the New York playground basketball wars featuring spectacular athleticism juxtaposed with devastating addiction and hardship, often within the same player.

Then there’s love of the game that goes way beyond that hoariest of clichés, as in Roy Blount Jr.’s profile of trick-shot specialist Wilfred Hetzel. Blount notes that Hetzel “has made 144 straight foul shots standing on one foot” and “bills himself as one ‘one of basketball’s immortals,’” but, alas, “has never learned to dribble.”

John Edgar Wideman explores what the neighborhood version of basketball means to two generations of his family (“The game, again like gospel music, propagates rhythm, a flow and go.…”) while novelist Pat Conroy delves into his real-life disappointments playing college ball at the Citadel in South Carolina. George Kiseda tells the wrenching story of Perry Wallace, the first African-American varsity scholarship player to play for a Southeastern Conference university as a member of Vanderbilt’s team from 1967 to 1970.

As the latter examples demonstrate, Wolff does not limit his selections to just big-name players, or even just to the NBA and NCAA blue bloods such as Duke and North Carolina or Kansas and Kentucky.

And, thankfully, Wolff isn’t just thinking about the boys-to-men aspect of basketball.

Douglas Bauer’s “Girls Win, Boys Lose” features the author’s high-school crush, who happened to be a hard-nosed member of their small-town Iowa basketball team. Bauer played for the boys’ varsity squad, but just barely, whereas Sue, his girlfriend, was a fierce and talented competitor on the court. The girls’ team wasn’t just better than the boys’ team, it was also the subject of more adoration and constant analysis among the farmers and other residents of Prairie City.

Bauer tells of Sue’s single-minded focus and grace, circumstances that left him kissing nothing but air on the many winter evenings when he leaned toward her in his 1951 Dodge while parked in front of her house. Sue, in Bauer’s telling, “would execute as neat a head fake as Pete Maravich” and hustle inside to continue her mental deliberations on the next game and the next opponent.

Speaking of head fakes, since you’ve made it this far, reader, let’s savor the best of the best as a buzzer-beater before this review runs out of time.

I remember reading Gary Smith’s Sports Illustrated profile of the late Pat Summitt – who died in 2016 of Alzheimer’s – when it was published in 1998. At the time, Summitt, whose flinty-eyed visage on the magazine’s cover left no doubt that the founder of the Lady Vols’ Tennessee basketball empire was no one to trifle with, was in her prime. So was Smith, as a second reading of his story all these years later makes clear.

Still, titles and wins mean nothing when the person under discussion is shown on a recruiting visit not only while pregnant, but after having her water break on a private plane on the way to the recruit’s house and still refusing to turn around. That’s what Pat Summitt did, among many, many acts of relentlessness and determination, a terrific story birthed by Smith through what must have been a near-endless series of interviews (and re-interviews) with not just Summitt but everyone in her orbit.

With all of his hard-won nuggets in tow, Smith can, and does, describe Pat Summitt with absolute certainty: “You don’t know that she’s spitting Nature in the eye and kicking Time in the teeth.”

It’s a fitting tribute to one of the greatest coaches in the game’s history and one of many reasons this collection is a slam dunk for anyone who loves basketball.