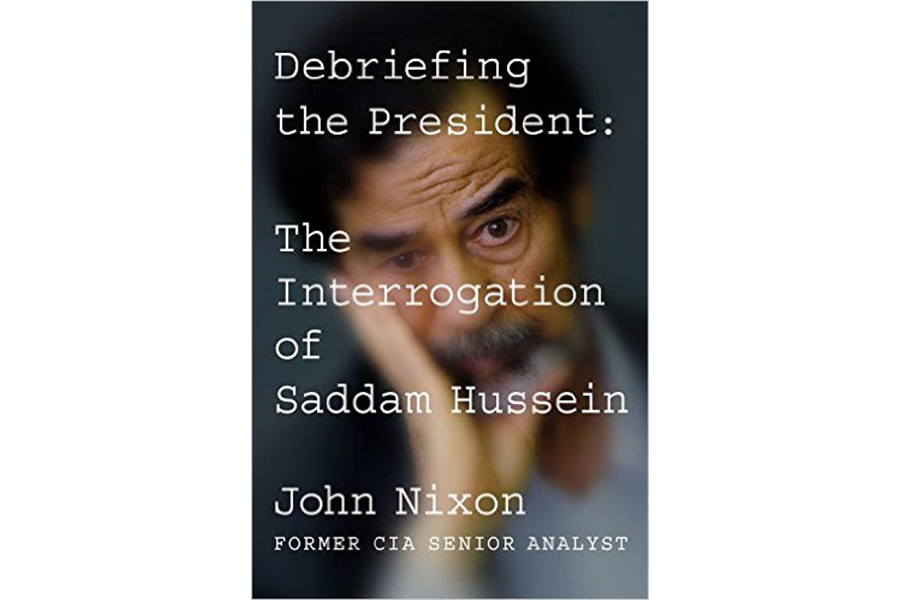

'Debriefing the President' details the CIA's interrogation of Saddam Hussein

Loading...

The clash of expectations that Hannah Arendt would later make famous in her book "Eichmann in Jerusalem" as “the banality of evil” arose from comparing the scope of Adolf Eichmann's crimes as the main architect of the Nazi Holocaust with the man himself who sat behind bulletproof glass during his trial in 1961. Arendt and all the other journalists present couldn't help but notice the contrast between the generation-maiming atrocities done on Eichmann's orders and Eichmann himself, described with a kind of bewilderment by Arendt as “terribly and terrifyingly normal.” Learning the scope of sheer suffering involved, witnesses at the trial expected larger-than-life monster and got a worried-looking bureaucrat instead.

As even its title makes clear, John Nixon's fascinating new book Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein doesn't suffer from this distracting contrast. Nixon was a CIA analyst when Saddam was dragged, filthy and wild-eyed, from a spider-hole near his native town of Tikrit in December of 2003, but Nixon had long been obsessed with the Iraqi dictator. “For years at the CIA, I lived and breathed Saddam,” Nixon writes. “Sometimes I just couldn't stop thinking about him; he was on a video loop in my brain.”

For a brief window of time (“The FBI will be out here in a few days,” Nixon is told. “We have him until then. Find out what you can”), Nixon and his fellow specialists and their interpreter get a chance to act on this obsession: they have uninterrupted access to the former “Butcher of Baghdad,” at first for purely practical reasons – to use their knowledge of the man in order to determine that the prisoner was, in fact, Saddam – but then to learn from his own lips whatever details of his story he was willing to tell.

“Willing” being the key word. Despite the subtitle of Nixon's book, the actual questioning sessions were conducted more like presidential interviews than armed forces interrogations; even the hint of police-style interrogation would prompt the prisoner to outbursts of indignation. Saddam had been cleaned up and given medical attention in the days immediately after his capture, and it had given him time to adjust to his new setting. This was a crucial missed opportunity; “Almost anyone with experience in questioning prisoners will tell you that the first twenty-four to forty-eight hours are crucial,” Nixon writes. That's when the shock of capture is still fresh.

By the time Nixon and his team meet Saddam, the former dictator has regained his internal footing and has become again what journalist Mark Bowden once memorably described as “the star in the truly epic tale of his own life,” a man who would sometimes draw himself up and snarl at his captors, “I am Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti, president of Iraq. Who are you?” No banality of evil here – by the time Nixon talks to the man, the banality is gone and only the evil remains.

Evil and considerable charm, as his questioner is perhaps a touch too eager to stress. “Whatever his atrocities, there was no denying that Saddam had great charisma,” Nixon writes. “He was a big man, six-feet-one and thickly built. I am six-feet-five but Saddam seemed oblivious to the difference. He was a man who had an outsize presence.” The Hollywood-style touch of the height comparisons tends to soften that atrociously blasé “whatever his atrocities.” Long before the book's final pages, it's clear that Saddam's baleful magnetism, the hallmark of the psychopath, had not deserted him in the face of his captivity. When Nixon asks him unwelcome questions about the 1988 gassing of the Kurds at Halabja, he tells us “no one ever looked at me with such murderous loathing as Saddam did that day,” but he seems almost proud of the distinction. And his conclusion “As of this writing, I can see only negative consequences for the United States from Saddam's overthrow” is, to put it gently, open to debate.

But there was no bulletproof glass during these questioning sessions, no gallery of spectators, and perhaps most importantly, no courtroom testimony from victims. Instead, there was only the man and his interrogators, and Nixon captures the psychological give-and-take of these exchanges with gripping readability – there's a two-actor smash Broadway hit play waiting to be crafted from these pages. Nixon had only a very short amount of time to try to get past the formidable mental and rhetorical defenses Saddam had built over a lifetime of cruelty and hypocrisy, and he describes the resultant verbal sparring with a sharp ear for nuance.

The ending is fore-ordained, of course. Eventually Saddam is taken out of CIA hands, interrogated further, and in short order turned over to the interim Iraqi government for trial and execution. He was hanged in December of 2006, shouting defiance at his executioners with his final breath. "Debriefing the President" is as much of the man himself as we're ever likely to know.