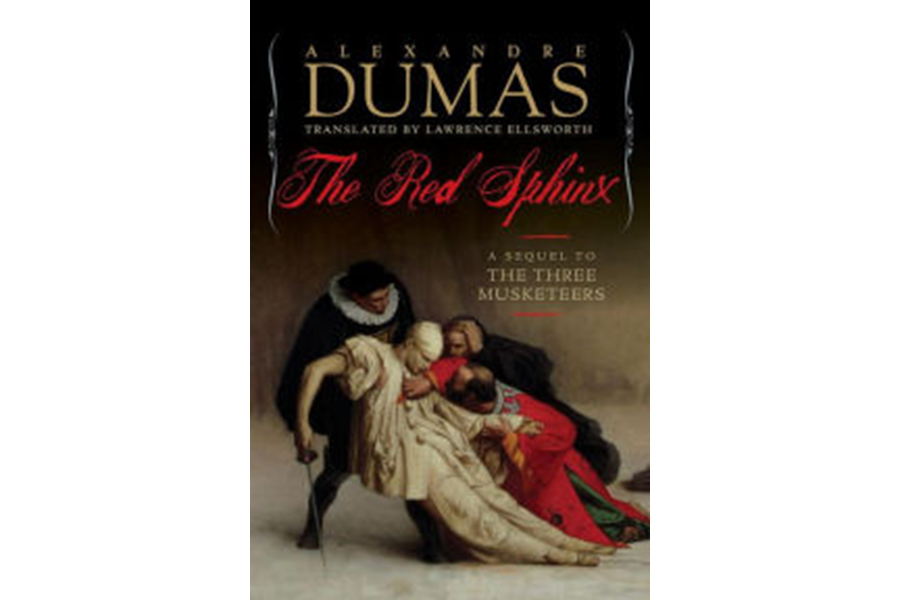

'The Red Sphinx' sparkles and shines in a new translation

Loading...

Can there possibly be a more jubilant start to any bookish year than a whopping big new novel by Alexander Dumas?

It's The Red Sphinx, an 800-page wonder newly published by Pegasus Books, and as translator Lawrence Ellsworth points out in his Introduction, it's not precisely new. After a larger-than-life career of epic successes on stage and page, after self-imposed exile from France and then eventual return, after writing world-cheered bestsellers like "The Three Musketeers" and "The Count of Monte Cristo," after presenting friends and mistresses and anonymous ghost-writers with impromptu gifts of lavish proportions, after the prime of appetites that seemed incapable of sating, Dumas, older but no wiser, attempted to recapture the glory of the cliffhanger historical potboiler that had made him a household name on three continents.

He found a publisher eager to try it, and Le Comte de Moret was serialized in "Les Nouvelles" in four parts, from October 17, 1865 to March 23, 1866. The work was named after its ostensible hero, the dashing Comte de Moret, half-brother to France's King Louis XIII, but its informal title, "The Red Sphinx," was more apt, referring to the character who thoroughly dominates the book, King Louis's all-powerful and inscrutable Cardinal Richelieu. The Cardinal's feared major domo, du Tremblay, was known as “the Gray Eminence,” but nothing compared to the Cardinal's power under the King's favor. When one character in the novel gasps, “You must be no less than his Gray Eminence,” the cardinal drawls, “Oh, better than that … I am His Red Eminence.”

Readers of "The Three Musketeers" and its more-famous sequels will recall the complex affection Dumas had for His Red Eminence, but it wasn't enough to turn Le Comte de Moret into a success. As Ellsworth relates, the book languished for a century in France, although bad translations and unauthorized sequels flourished in 19th-century America. Then, in what Ellsworth calls “a dramatic event so unlikely that it could have come from the pen of the master himself,” a substantial chunk of Dumas's original handwritten manuscript was found in 1945 in Paris, leading to the 1946 book-publication of Le Comte de Moret in two volumes.

That version of the book's story is unfinished, and it's appended in this new Pegasus volume with a story called "The Dove" ("La Colombe" in French), which was originally published in Brussels in 1850 and which in many ways, according to Ellsworth, forms the real conclusion to the incomplete text of "The Red Sphinx." "The Dove" here gets its first English-language translation in the United States. The combination of newly-translated potboiler and newly-translated capstone novella makes this new edition of "The Red Sphinx" feel as complete as an unfinished novel possibly could.

As fans of Dumas will anticipate, the actual plot of the novel very much takes a back seat to the author's signature strong suits of action and snappy patter. Reminding readers of Dumas's theatrical background, Ellsworth writes, “Dumas wrote in scenes, vivid set-pieces conveyed by sharp action and even sharper dialogue, punchy lines meant to carry impact all the way to the cheap seats at the back of the hall.” Throughout "The Red Sphinx," Dumas, described by Ellsworth as “the living embodiment of joie de vivre,” is having such a grand time telling his story that readers will be smiling through a hundred exchanges like this one:

“Your Eminence, would you care to guess who I met at the corner of the Rue du Plâtre and the Rue de l'Homme-Armé?”

“Who?”

“Disguised as a peasant of the Pyrenees ...”

“Tell me instantly, du Tremblay! It's getting late, and I don't have time to spare.”

“Madame de Fargis.”

“Madame de Fargis!”

The adventures of the Comte de Moret are vividly told in these pages, but the real star of this show is Richelieu, who must pit his serpentine honesty against not only the enemies of King Louis (the scenes of one-on-one conversation between the two men are consistent highlights in the book crammed with action scenes) but also against his own enemies at Court, including the most implacable of those enemies, the King's own mother. Ellsworth relates that Dumas wrote these segments at the end of his life and not at the peak of his powers, but even an Alexander Dumas who's slightly off his game is still better storytelling company than the next 10 writers on their best days. Thanks to this great new translation, "The Red Sphinx" races along and sparkles everywhere with both broad humor and pointed quips, as when the King laments not being as wealthy as some of his favorites and the Cardinal replies,

“The king doesn't need to be rich, he's the king. If he needs a million, he asks for a million, and it is found.”

In his Afterword, Ellsworth confesses that translating Dumas is “a lot of fun,” but he need hardly have said it: Fun permeates this big book. The rest of 2017's fiction will have to look sharp: An old master has just set the bar very, very high.