'Travels with Henry James' brings together 21 gems of travel writing

Loading...

What is the difference between the Great Lakes and the ocean? A scientist will tell you that the ocean contains saltwater, of course, and a vast ecosystem; the moon’s gravity also exerts a greater pull on it, establishing the tides. Asked the same question, a gifted novelist – indeed, a master – will tell you less, but also more. Twenty-eight-year-old Henry James, gazing for the first time on Lake Ontario in 1871, described what he saw this way: “It is the sea, and yet just not the sea. The huge expanse, the landless line of the horizon, suggest the ocean; while an indefinable shortness of pulse, a kind of gentleness of tone, seem to contradict the idea. What meets the eye is on the ocean scale, but you feel somehow that the lake is a thing of smaller spirit.”

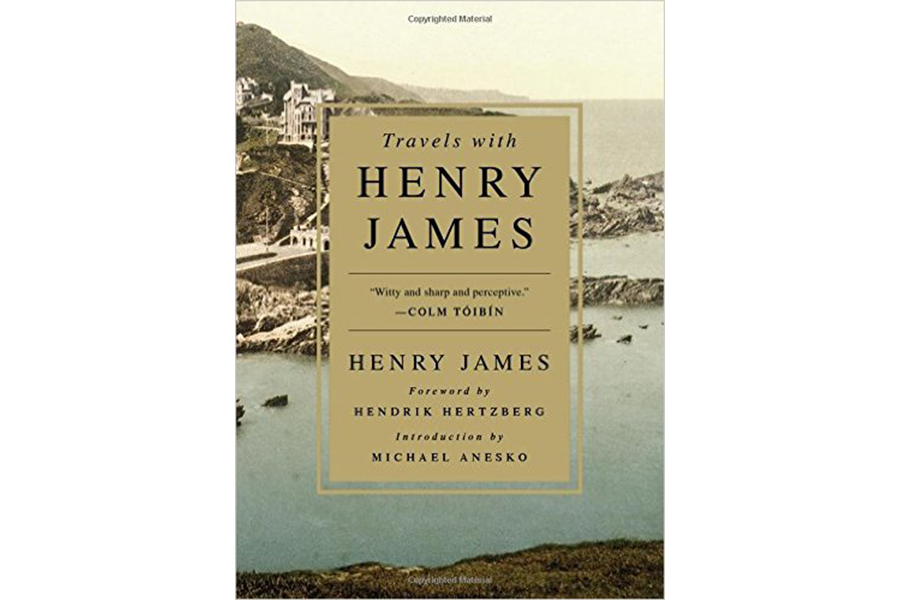

James’s essay is part of a new collection, Travels with Henry James, which brings together 21 gems of his travel writing between 1870 to 1879. The irony of the book is that the author – so famous in his novels for depicting society in Boston and New York, Paris and London, along with the minute gradations in his characters’ thoughts – writes most movingly, as a travel correspondent, when his subject is nature. After viewing Lake Ontario, he proceeds to Niagara Falls, where he is most struck not by the raw power of the plunge but by the beautiful arc of the water: “[I]t flows without haste, without rest, with the measured majesty of a motion whose rhythm is attuned to eternity.” If only James had lived to see the centenary of our national park system, which has protected scores of similar treasures across the country, and especially in the West.

"Travels with Henry James" does not see the West; in fact, James never even approached the Mississippi. Although the mountains of Wyoming and the mesas of Utah might have set his pen on fire, one senses that the urbane and waistcoated James could not have endured truly wild frontier. He confined his American itinerary to a half-dozen locations in the Northeast. James presented the resulting travel essays to The Nation as a sort of audition for a broader assignment to Europe. The magazine wisely agreed, sending him to England and then the Continent, where he filed travel reportage throughout his thirties. He took in towns and cities, cathedrals and frescoes, never overlooking the denizens of these cultured lands: women in their frocks, men checking their pocket watches; the fashionable and garish, the gauche and homely. Nothing goes unobserved by his generous eye.

He is more democratic in his tastes than a reader of novels like "The Ambassadors" or "The Portrait of a Lady" might expect. Some of the grand attractions of Europe leave him cold. “There are people who become easily satisfied with blonde beauties, and Salisbury Cathedral belongs, if I may say so, to the order of blondes.” Several of James’s favorite vistas in town are not in the fashionable quarter but at the seaport or near the tracks. He is certainly no muckraker or bleeding heart, and still less a contrarian; he simply pursues the line of beauty where he finds it. This includes the “mouldy-timbered quiet” of old Newport. Through these pages he wanders and pauses, searching out the new and the unexpected. “I can wish the traveler no better fortune than to stroll forth in the early evening with as large a reserve of ignorance as my own, and treat himself to an hour of discoveries.”

The English countryside holds a special appeal – James writes of “this interminable English twilight, which I am never weary of admiring, watch in hand” – and Paris is Paris, but nothing compares to Italy. Here James finds the intersection of beautiful country, structures, people, and light. While observing an open-air theater rehearsal on a Roman afternoon – too far away to hear but comprehended through “the generous breadth of Italian gesture,” he captures the magic of the country in a few simple lines. “It was all deliciously Italian – the mixture of old life and new ... the dominant presence of a mighty architecture, the lounges and idlers beneath the kindly sky, upon the sun-warmed stones.” I can think of no other writer, except perhaps Saul Bellow or Vladimir Nabokov, with so sure an ear for the music of prose.

Beyond the light it sheds on the master himself, this collection wonderfully expresses the sheer pleasure of travel. Visiting Stonehenge, James seems not to want his day to end. At leisure, with the new and the beautiful in prospect, a person can forget all troubles and bathe in the warm glow of happiness. “I can fancy sitting all a summer’s day watching its shadows shorten and lengthen again, and drawing a delicious contrast between the world’s duration and the feeble span of individual experience.” The only thing that would improve such a day is the company of this book.