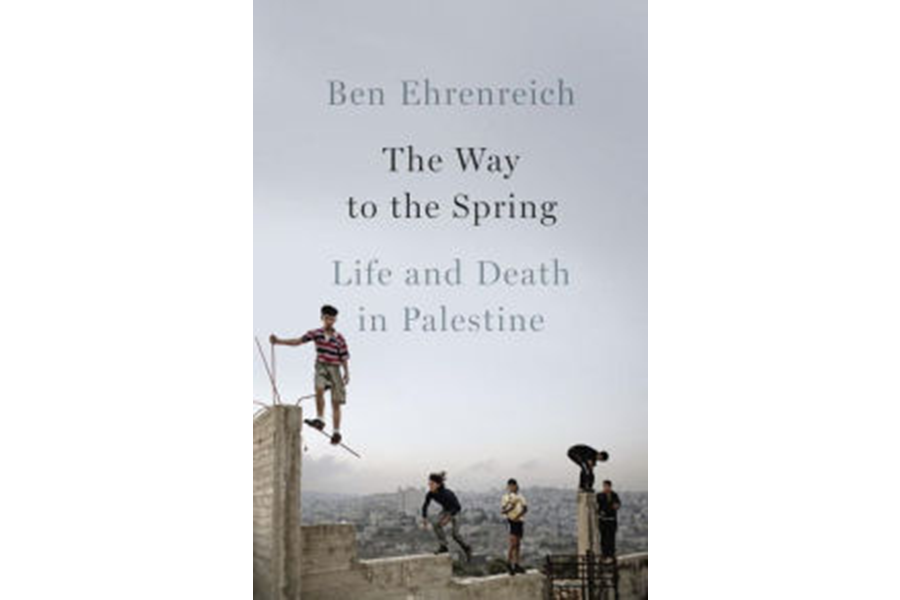

'The Way to the Spring' chronicles the frustration, heartbreak of Palestinians

Loading...

Novelist and journalist Ben Ehrenreich centers his utterly heartbreaking new book, The Way to the Spring, on small communities like Nabi Saleh, a small town 25 minutes northwest of Ramallah in Palestine's West Bank, and on a small cast of people who live in towns like Nabi Saleh and Ramallah and Hebron. Ehrenreich disavows any idea that his book is intended to speak for or “humanize” the men women he meets (he calls the latter “a favor they do not need from me”); rather, he seeks to correct what he sees as an imbalance. “The world – the human part of it anyway – is made not only of earth and flesh and fire,” he writes, “but of the stories that we tell.”

His book tells dozens of those stories, sketching the lives and passions and frustrations of people like protestor Bassem Tamimi and his wife Nariman, their sons and daughter, activist and teacher Issa Amro and his brother Ahmad, New Jersey-born Hebron spokesman David Wilder, sculptor Eid Suleiman al-Hathalin, and many more. Ehrenreich moves among them, visits their homes, shares their meals, and again and again in the course of the book seems surprised and touched by the quiet resolve, even the grace, with which they bear up under day-to-day circumstances that would very quickly drive most of this book's readers to complete despair. In the place of that despair, our author usually finds a mixture of low-simmer rancor and resignation; “This is our lives” he hears over and over.

The Israel Defense Force (IDF) and the Israeli Border Patrol police the West Bank with the bored callousness of conquerors. They have been touring these towns and neighborhoods, ransacking these homes and businesses, and occasionally killing these civilians since the occupation began in 1967, and the incidents related by Ehrenreich's interview subjects quickly take on a galling sameness in their brutality and injustice. In one of these stories, a squad of Israeli paratroopers enters the city of Qalqilya and shoots Saleh Tassin, a 28-year-old officer in the Palestinian Authority (PA)'s intelligence bureau. “The IDF claimed that their victim, whom the soldiers had left to bleed to death in the street, had fired first,” the story goes. “Palestinian witnesses maintained that he did not fire at all.”

The inhabitants of towns like “Planet Hebron” (“If Hebron were hidden away on a mountaintop or deep in a canyon at the bottom of the sea, if getting there meant descending through dim, crumbling shafts to the center of the earth, or undergoing cryogenic treatment in preparation for a multi-light-year journey, it wouldn't feel so odd”) face this kind of violence virtually every day, and Ehrenreich is a keen observer both of the ways this has deepened their family bonds and also the way it's sharpened the cynicism of everybody he meets. “Being shot at can have a profound effect on people. It makes things suddenly concrete, urgent, real,” he writes. “It makes you choose a side, or better put, chooses one for you.”

The goal of eliminating those sides, of reaching an actual peaceful accord, always seems cartoonishly unreal when laid alongside the beatings, cripplings, bulldozings, tortures, and murders the IDF inflicts on its Palestinian prisoners every day, or the Palestinian violence that increasingly throughout the book looks like an almost involuntary desperation, a reflex against having almost no freedom and no hope whatsoever.

Ehrenreich knows better than to offer that kind of hope, especially since the events of his book are leading inexorably to Israel's massive 2014 bombardment of Palestine in alleged retaliation for the deaths of three Israeli boys in April of that year. The violence appalled a watching world whose international law courts had long since already condemned Israel's West Bank settlements as flagrantly illegal, and yet that outrage made no difference in either the short term or the long term.

On Sunday, June 19 of this year, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu announced the Israeli government's plans to an additional $18 million into West Bank settlements, the money allegedly earmarked for “security” purposes and also to enhance tourism. The leader of the PLA called the move “a slap in the face of the international community,” but for lives this book describes, it means a continuation of their ordinary nightmares. Their shops are still shattered; their electricity and food and water and movement are all still ruthlessly rationed and controlled. Bullets still punch through their windows – nobody takes responsibility, nobody cares when it's reported. Molotov cocktails are still hurled onto their doorsteps – they've learned to deal with such things almost as a matter of course. Their children still walk to bombed-out and bullet-ridden schools through drifting clouds of tear gas.

For those ordinary people of the West Bank, whose lives Ben Ehrenreich has so sadly and wonderfully chronicled in "The Way to the Spring," it means a further tightening of the noose, the light of a better future receding that much farther away.