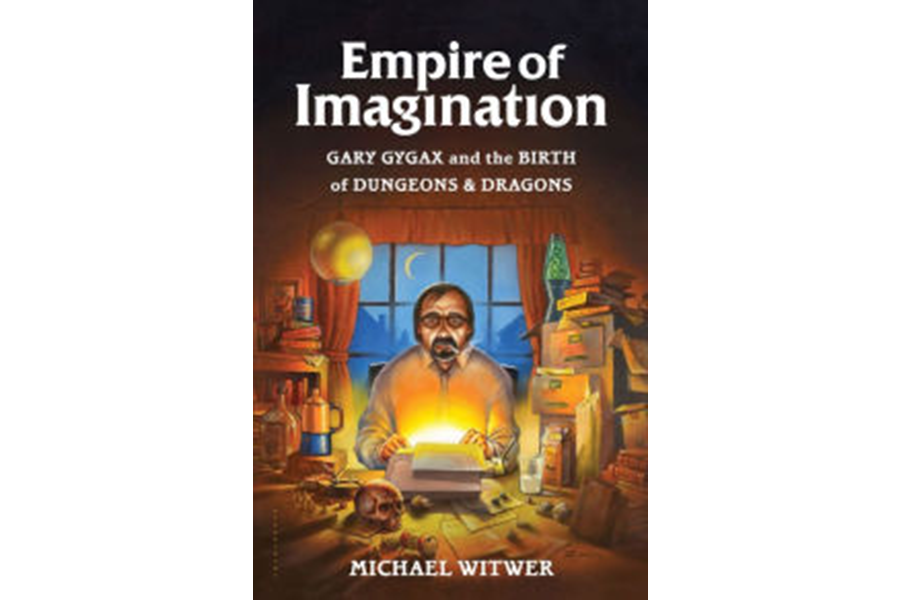

'Empire of Imagination' is the first full biography of 'Dungeons & Dragons' creator Gary Gygax

Loading...

"Why are Americans afraid of dragons?” Ursula Le Guin asked in 1974. That same year, the year Le Guin bemoaned the “Puritanism,” “work ethic,” and “profitmindedness” that stayed hands from the fantasy shelves, was the year that "Dungeons & Dragons" arrived in hobby shops across the country. In 1974, also the last year of Nixon’s presidency, there were few mainstream fantasy strongholds "D&D" could seize onto as models for successful escapist enterprises in America. Its subversive unreality struck at the core of down-home Americans: Churchgoing parents claimed they saw underpinnings of the devil in the game’s rulebooks. One attested that, if fed to a fire, "D&D" books would scream uncontrollably as they burned. (Co-creator Gary Gygax denied this fantasy, among others, and allegedly offered a $1 million reward to anyone who could incite even one shriek from his tomes.)

Rumors abounded that it was possible for players of "Dungeon & Dragons" to transcend their bodies altogether while in-game, viewing their miniatures and maps from a few feet above their abandoned flesh. Another account, this time by a Texas-based PI, described how a computer science student and "D&D" obsessive escaped to the steam tunnels under his college to live out role-playing fantasies under the feet of his classmates. In any case, above or below ground level, players of the game were considered detached from the Americana of the moment: a country defined by war, fenced-in properties and the Main Street business habitat that sustained Gary Gygax’s middle-class existence until he made it big with fantasy. It’s no secret that "Dungeons & Dragons" has for decades been a punch line in mainstream American life.

It should be no surprise, then, that the cultural undercurrents that made America’s soil arid for escapist enterprises didn’t just randomly generate "Dungeons & Dragons." The same ideological riptides that dragged fantasy underground sprang forth wargaming, "D&D"‘s rationalistic and anti-theatrical older brother. Needless to say, their relationship was fraught. What is perhaps the greatest producer of fantasy culture today, it turns out, suffered at first from an uneasy relationship with the fantasy genre, just as America suffered from an uneasy relationship with it. For the same reasons that orc massacres and inter-planar demons had suburban mothers fretting over what was going down in the basement rec room, "Dungeons & Dragons" and its co-creator navigated the realm of tabletop gaming with great difficulty before eventually finding its perch at the pinnacle of escapist outlets.

The ironic reality is that Gary Gygax was, in many ways, the embodiment of American virtue, despite his professedly unintentional foray into fantasy gaming. A Wisconsin-bred Jehovah’s Witness, Gygax fostered dreams of military glory between his service with the Young Republicans and marriage to the redheaded childhood sweetheart from Lake Geneva, his hometown. Empire of Imagination, the first full biography of Gygax, memorializes these down-home qualities of Gygax’s countenance – qualities quite opposed to the way "D&D," his child of sorts, has struck its fans. Author Michael Witwer, who pays tribute to “the Good Lord” in the acknowledgments, composes a sort of fanfiction around Gygax’s life, complete with scenes depicting him fishing for bass on Lake Geneva and undercover Army Intelligence agents infiltrating his gaming circle (“fanfiction,” I say, because a FOI request to Army Intelligence yielded no official corroboration).

Gygax’s brief foray into the Marines was either the root or a symptom of a lifelong obsession with wargaming. As Witwer has it, Gygax was motivated by the concept that “every man wants to be the hero of his own life.” Unfortunately, walking pneumonia and his poor physical condition led to his near-immediate discharge. But the same impulse that led him to boot camp – his penchant for military strategy and cold, dry history – ushered him into the world of role-playing games. "Empire of Imagination" has him reaching for Col. Mustard, the colonial imperialist, every time he played "Clue" growing up.

By December 1958, at age 20, Gygax was enamored of the strategy role-playing game "Gettysburg" (“NOW YOU CAN FIGHT THE CIVIL WAR BATTLE IN THIS REALISTIC GAME”), published by Avalon Hill. In wargaming, every player can take on the role of Napoleon at Austerlitz or Grant at Chattanooga – just, please, forego any theatrical voices.

The mass appeal of commercial miniature wargaming in ’50s and ’60s America, on the heels of World War II and the Korean War, indicated America’s psychic bearing at the time. Players would control miniature human armies, often complete with ships or tanks, and governed by a specific set of rules, try to win in a battle of wit and abstract brawn. The first, and perhaps most popularized, inception point for this kind of gaming was US Army Reserve Infantryman Charles S. Roberts’s 1954 "Tactics." Slated to be drafted for the Korean War, as the story goes, Roberts designed the tabletop game to understand the virtues of war. Roberts soon recognized the commercial appeal of the game and marketed it with great success to like-minded strategists interested in battle tactics. The combination of entrepreneurship and military caprice proved a quintessentially American formula.

Roberts is credited as the father of commercial miniature wargaming as we know it, though perhaps the first stab hobby wargaming was decidedly un-American: Englishman H. G. Wells’s "Little Wars" (1913). Players (“boys” and “that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books”) controlled cavalry, artillery, and infantry to play out, well, little wars. By some accounts, however, the architect of commercial, miniature-based wargaming as we know it was famous not only for his science fiction and fantasy but his pacifism. Touchingly, he hoped his game would mitigate players’ desires to enact war: Pouring themselves into this sort of fantasy would further distinguish pulp war fiction from peace.

Gary Gygax actually wrote a foreword to the 1970 reprint of "Little Wars," noting that World War I’s start in 1914 may have been what forced the wargaming hobby underground until Roberts unearthed it. Gygax had not heard of "Little Wars" when he began designing games, but he admits that Wells’s “subterranean humans in the 'Time Machine'” inspired "D&D"‘s signature “dungeon-crawling” motif. Its fire-breathing dragons, dwarves, and orcs would be appropriated from a source less palatable to the boot camp dropout Gygax.

The play-by-mail game "Diplomacy," simulating a pre-WWI alternative history and Napoleonic naval games ("Don’t Give Up the Ship") led Gygax out of the life of an insurance writer and into the position of editor-in-chief of Guidon Games. In that capacity, he co-designed "Chainmail," the precursor to "Dungeon & Dragons." Analytical and highly strategic, the medieval wargame modeled crusade-style combat: sword-sans-sorcery. But with the 1971 publication of "Chainmail" in the Castle & Crusade Society’s newsletter came a pivotal but fraught “afterthought”: a 14-page “Fantasy Supplement.” Among diehard wargamers, fantastical scenarios proved immensely controversial. Wizards, dragons, elves, and a taxonomy of other fantasies pushed at the seams of Gygax’s cold-cut historical fiction game. Gygax noticed that convention-goers (much like suburban mothers years later) wrote it off as a frivolous puppetmastery of “make-believe fairy tale creatures.” At first, even Guidon Games’ advertisements of "Chainmail" hinted at embarrassment: the supplement contained “Super-heroes, wizards, trolls, hobbits and (why not) dragons.”

While a professed ambivalence (in the form of mail-in polls) indicated that early ’70s fantasy gaming would be a bust, Gygax’s experiences at conventions proved otherwise. According to his justifiably biased account, 90 percent of his audience introduced to “fantasy wargaming” in person were enamored. Because of this, and because of a boom in the popularity of J.R.R. Tolkien’s "Lord of the Rings" trilogy in the late ’60s and early ’70s (when the books were re-released), Gygax expanded "Chainmail"‘s fantasy supplement into today’s bastion of sword-and-sorcery gaming, "Dungeons & Dragons."

Originally published in 1955, Tolkien’s trilogy built a coherent fantasy world in which a party containing a hobbit, a dwarf, an elf, a human, and a wizard battled various creatures to ensure good’s triumph over darkness. Likewise, Tactical Studies Rules, Inc.’s 1974 "Dungeons & Dragons," commonly considered the inception of modern role-playing games, allows players to inhabit hobbits (later, “halflings”), elves, dwarves, and wizards. The connection was hard to mistake.

Even as his game accommodated the more warlike sensibilities of the everyday conservative, Gygax forthrightly appropriated Tolkienesque fantasy for "Dungeons & Dragons." In a 1979 New York Timesspecial report, Nathaniel Shepphard deemed it “an apparent takeoff of the popular J.R.R. Tolkien Trilogy.” But it was either Gygax’s pride or a handful of litigation threats from the Tolkien estate that led him to spend the next few decades trashing everything Tolkien.

“The ‘influences’ from JRRT’s work that I included in the game were mainly there to interest others in playing it, not what caused me to want to create it,” Gygax later insisted. It was its “popularity,” he maintained, was what he aimed to capitalize on; not its content. The books were, to him, “not dynamic” and “tedious.” “I must say that I was so bored with his tomes,” Gygax claimed in a perfect humblebrag, “that I took nearly three weeks to finish them.”

It was these Tolkienesque components of the game that also drew criticism from old-line wargaming community and conservative Americans at large. Tolkien himself displayed a pacifist streak: Though a veteran of World War I, the fantasy novelist vocally disapproved of aerial bombardment, nuclear weapons and other apparently inhumane war tactics. In "The Lord of the Rings," the hobbit Frodo’s quest is to destroy an evil weapon rather than to triumph in battle, and his secret weapon is his good-heartedness. Critics have cast his trilogy as an allegory for World War II (Sauron as Hitler, the ring as an atom bomb). Gygax, on the other hand, was a fan of pulp fantasy, books that glorified war: Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian), Fritz Lieber ("Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser") and Michael Moorcock ("Elric"). "Dungeons & Dragons," despite its famously intricate battle rules and statistic tables, relies as much on combat strategy as Tolkienesque “playing make-believe fairy tale creatures,” a decidedly surreal and escapist pursuit detached from the aesthetic and historical thrust of wargaming.

Gygax pitched the game to Avalon Hill and Gideon Games. He marketed "D&D" as a wargame, founded on the same principals of combat simulation as Gygax’s longtime favorites. “The reception was a trifle chilly,” he later said. “The ‘establishment’ was not about to jump into something as different and controversial as fantasy.” The publishers fundamentally underestimated America’s desire for an escape. Subversion was in, and by 1974, war was out: The Vietnam War would end one year later after half a dozen years of protest.

As a twist on Roberts’s move to build Avalon Hill around the wargame "Tactics," Gygax co-founded Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. (TSR) in part to accommodate "Dungeons & Dragons." By February 1979, the game had doubled its sales every year since its release in 1974. Close copies such as "Tunnels & Trolls" immediately manifested to capitalize on momentum toward the fantastical. Tactics took a backseat as theatrical role-playing and storytelling became drivers of player adventures. Images of geeks sitting around a table, faces lit by candlelight, putting on airs as “Quoltar the Paladin Avenger” – who seeks some lost-lost jewel in the name of his exalted deity – overshadow any deadpan wargaming model that prefaced "D&D." But as the game expanded, Gygax, TSR’s president and chief executive officer, was overthrown by the company he created. The most powerful figure in wargaming lost control over his corporate vision in 1986 when shareholder positions shifted such that Gygax was ousted. He took to writing novels. “The shape and direction of the 'Dungeons & Dragons' game system,” Gygax wrote in a farewell letter in 'The Dragon,' ... are now entirely in the hands of others.”

Wizards of the Coast, which is owned by Hasbro, released "Dungeons & Dragons"’ fifth edition in 2014. Worth $8 billion, Hasbro, a well-known, all-American consumer brand, has validated "D&D"‘s entry into the American mainstream. Stephen Colbert, Vin Diesel, Mike Myers, and other commercial superstars have ratified the fantasy kingpin’s seat atop American cultural products. And as its relevance soars, with mentions in "Wet Hot American Summer" and "The Big Bang Theory," its fantastical underpinnings overshadow its wargaming roots. Mike Mearls, "D&D"‘s head of research and design and co-lead designer for 5e, cited Ursula Le Guin’s "Earthsea" series as his main inspiration for the latest rule set. Mearls, an unabashed Tolkien fan, was similarly influenced by Octavia Butler’s "Parable of the Sower." “As fantasy has grown, the characters it has presented have become more nuanced and broader in scope,” Mearls told Forbes, “we knew that we had to make a fairly flexible game to capture the types of characters people wanted to create or emulate.”

In 1977, fantasy gamers could consult the “Harlot Table” to determine whether a “wanton wench” or “haughty courtesan” would fall into their lap at a local tavern. The newest edition of the game showcases a sensibly armored black woman as its example of the “human” race option. Its rulebook suggests that players “don’t need to be confined to binary notions of sex and gender.” You may command an army, or you can race alongside it as a peacemaking bard. The thoroughly male world of wargaming, a world that, as Witwer chuckles, evaded the understanding of Gygax’s wife (whom, as rumor has it, he chose for her resemblance to a fantasy pinup girl in skintight armor), has been exploded by "D&D"‘s goals of inclusivity. Fantasy gaming, using "D&D" as its springboard, has now evolved into something closer to Wells’s pacifistic aspirations or Tolkien’s way of seeing the infinitely manifold possibilities of story. Whatever else we have left to work through, 2015 America has made peace with dragons.