'The Fellowship' follows C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and friends through their defense of fantasy

Loading...

Writing a biography of C. S. Lewis – novelist, critic, poet, and Christian apologist – would be a difficult enough task. In The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings, Philip and Carol Zaleski have set themselves an even harder challenge: writing a group biography of the Inklings, the mid-20th century group of Oxford fantasists, scholars, and poets who met weekly, usually in Lewis’s room at Magdalen College, to drink beer, share works-in-progress, and boisterously argue over religion, poetry, mythology, and magic.

"The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" was first read aloud in this intimate setting, as were the epics of J. R. R. Tolkien. It’s primarily through these works, and through the group’s general advocacy for fantasy as a serious mode of the imagination, that the Inklings live on today. Every work of fantasy that kills at the box office, the Zaleskis argue, confirms a simple fact: We live in a culture that the Inklings helped create.

Who were the Inklings, exactly? This is a difficult question to answer. The cast of characters shifted frequently, with some (the man of letters Lord David Cecil) attending sporadically and others (the mystery writer Dorothy Sayers) existing just on the outskirts. In simplest terms, the Inklings was a literary and social club, a group of male friends – women weren’t allowed – who met weekly at Oxford from the 1930s to the 1950s in order to discuss their shared loves.

The Inklings were mainly, although not exclusively, believing Christians, and they all had serious reservations about philosophical materialism: the school of thought that sees all phenomena as ultimately reducible to matter and its interactions. The Inklings sensed that the world was stranger and wilder, more beautiful and more meaningful, than such an ontology suggested. They were interested in what the Zaleskis call “the rapture of the unknown”– those experiences that seem to put us in touch with something that transcends the material world – and they believed that fantasy, mythology, and poetry could help us access this world that both exceeds and suffuses our own. The Inklings were, as the Zaleskis write, “twentieth-century Romantics who championed imagination as the royal road to insight.”

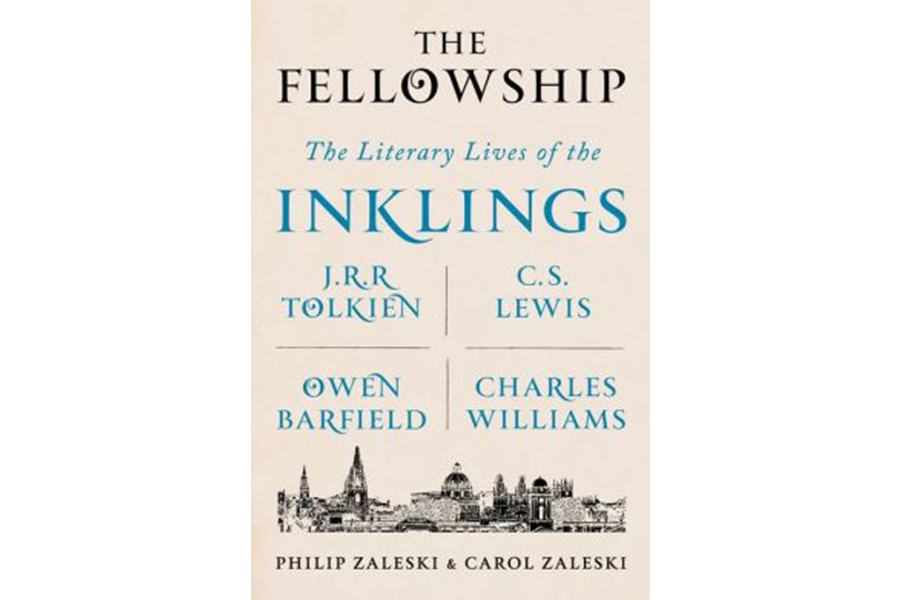

"The Fellowship" focuses on four members of the group: Lewis and Tolkien at the greatest length, but also Charles Williams, an Anglican poet, novelist, and occultist, and Owen Barfield, an Anthroposophist poet and thinker who made his living (unhappily) as a lawyer. The book, in other words, is really four biographies in one. In less able hands, this would be a recipe for narrative confusion and archival glut. But the Zaleskis deftly interweave the four stories, showing how, when read together, these very different men can help us more clearly see the state of literary and religious culture in mid-century England and beyond.

Like any good biography, "The Fellowship" isn’t a mere assemblage of facts and events. It tells a story – a fact that the Inklings, defenders of traditional storytelling at a moment when literary modernism was calling the importance of plot into question, would appreciate. We encounter the group in its first, lively meetings in the late 1920s. Warnie Lewis, the famous author’s charming, dipsomaniac brother, reported early conversations about “torture, Tertullian, bores, the contractual theory of medieval kingship, and odd place-names.” We then follow the group through World War II, when Tolkien began reading bits from his proposed sequel to "The Hobbit." The Zaleskis emphasize the liveliness of the continuing conversation: Lewis’s brawling style of debate, Williams’s overpowering charisma and “tinderbox mind.” (Some of the more memorable anecdotes center on Williams’s interest in sexual magic, which sometimes shaded into “ritualized sadistic behavior.”)

Perhaps the most interesting figure in "The Fellowship" is the less well known Owen Barfield. By and large, the lawyer/writer lived in the shadow of his more famous friends. But the Zaleskis bring Barfield to life again, especially in describing his brilliant and esoteric theories of poetry. Barfield was, the Zaleskis write, a “man obsessed with a single idea, the evolution of consciousness,” and he believed that the stuff of poetry, the words and images it used, were like fossils revealing the history of this evolution. Barfield thought that poetry mattered to the human soul and to human culture, and "The Fellowship" shows why Barfield might still matter to us today.

Eventually, just as in Tolkien’s "The Fellowship of the Ring," the group broke apart; petty squabbles and failing health proved too much. But this failure shouldn’t blind us to the conversations that were had and the work that these conversations helped produce. The Inklings created great works, to be sure, but just as importantly, the Zaleskis claim, they reclaimed “a universe created, ordered, and shot through with meaning.” This imaginative and theological vision was, and remains, a thing of great beauty and value.

Anthony Domestico is an assistant professor of literature at Purchase College, SUNY.