'When Books Went to War' tells how paperback books helped to win World War II

Loading...

When American troops stormed Omaha Beach during the D-Day invasion of France during World War II, they faced a barrage of German machine-gun fire and almost certain death. Troops that landed on the beach later in the day encountered an incongruous sight: grievously injured soldiers propped up against the base of the cliffs of Normandy who were reading books while waiting for the medics to arrive.

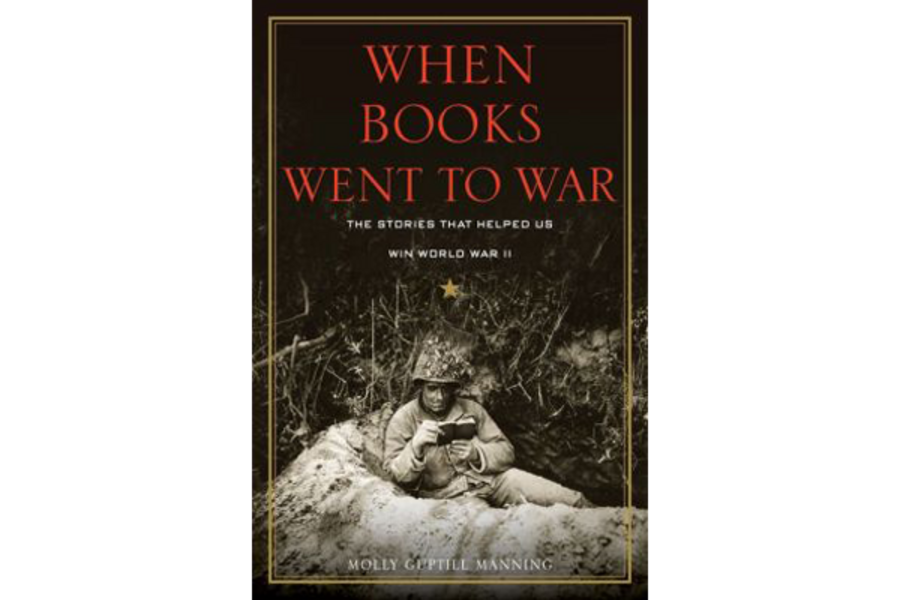

This sobering yet uplifting image is just one of countless examples of how books helped the Allies win World War II, a story chronicled in When Books Went to War, by lawyer and author Molly Guptill Manning. In her new book, Manning charts the efforts of the American public and the US government to provide books to the service members fighting overseas. It’s not often that a history book tells a story that’s for the most part inspirational and optimistic, but that’s exactly what Manning’s manages to do.

Manning’s book is built on the notion that World War II was a war of ideas as much as an actual war. The US was fighting a foe that had burned thousands of books in the 1930s and poisoned the minds of its own people with propagandistic texts.

By contrast, Manning argues that the US fought for intellectual freedom by actively encouraging reading during the war. When America mobilized for war in the early 1940s, the government immediately laid plans to bolster flagging morale by distributing books. Donations flooded in from around the country. Later in the war, the Council on Books in Wartime pioneered a new innovation: the pocket-sized Armed Services Editions.

For many soldiers, these ASEs provided both escape and catharsis. For example, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” the classic tale of a New York girlhood, became so popular among soldiers that author Betty Smith received four letters from service members per day.

Manning does tackle questions about intellectual freedom in the US during that same period. She devotes a chapter to the fight over censorship in the lead-up to the election of 1944, showing through the results of that fight that the US was indeed better than its enemies. Throughout the war, the Council on Books promoted a wide range of titles and genres, with the exception of books that provided comfort to the enemy or promoted discriminatory attitudes.

Besides helping the Americans win the war through propagating intellectual freedom and free thought, the ASE program and the Council on Books turned many service members into lifelong readers. And the ASE program popularized many of the books we think of as classics today, including “The Great Gatsby” and “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” as well as making paperbacks a viable part of the postwar book trade.

Overall, Manning’s book is an uplifting examination of a little-known, intimate aspect of America’s most well-known war. It will appeal to bibliophiles, World War II enthusiasts, and anyone interested in the stories of the so-called Greatest Generation.

It will also appeal to anyone who likes a story with a happy ending: As Manning points out toward the conclusion of her tale, more books were given to American soldiers by the US government than were destroyed by Hitler.

Emily Cataneo is a freelance writer based in Berlin.