'Sons of Wichita' is a rollicking, revealing look at the powerful Koch brothers

Loading...

Their last name is pronounced like Coke, and that's absolutely appropriate. Although most people don't realize it, the powerful Koch brothers are as ubiquitous in our lives as Coca-Cola.

Koch Industries, the second-largest private company in the US, sprawls across 60 countries and employs 100,000 people. It controls vast quantities of oil, cattle, fertilizer, and timber plus consumer products like Brawny paper towels, Stainmaster carpet, and Dixie cups.

"A day doesn't pass when we don't encounter a Koch product," writes journalist Daniel Schulman. Neither does a day go by without voices declaring that two of the four Koch brothers are trying to destroy the country by buying elections and unleashing the Tea Party.

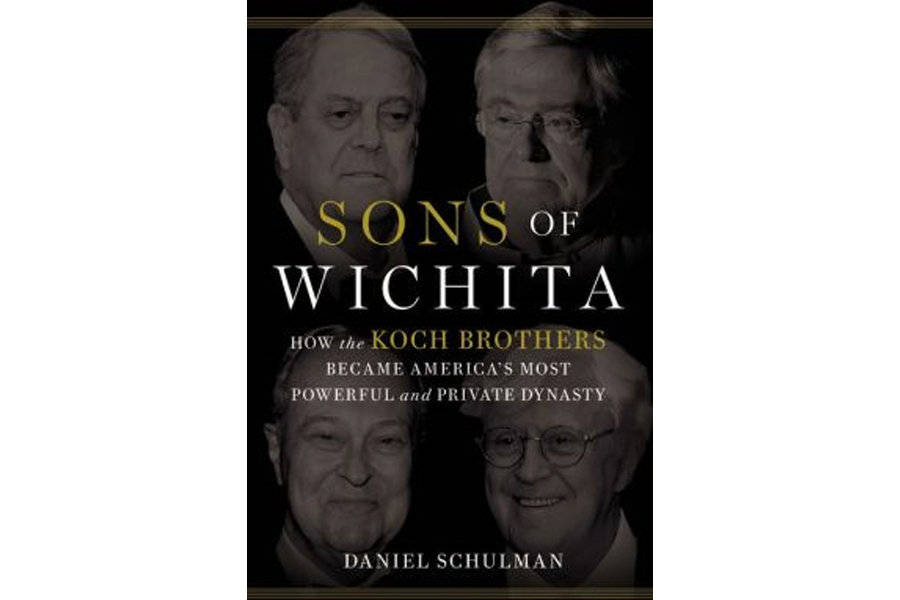

In his rollicking and revealing new book, Schulman cuts through the fog of political warfare to uncover complicated lives of power, privilege, and politics. While Schulman is a reporter for the liberal muckraking magazine Mother Jones, readers of all political persuasions should appreciate the cautious yet fascinating journalism in Sons of Wichita: How the Koch Brothers Became America's Most Powerful and Private Dynasty.

The most surprising revelations in "Sons of Wichita" come in Schulman's portrayal of the tough and dysfunctional Kansas childhoods that produced the tough and dysfunctional modern Koch dynasty.

The brothers' father, a Midwestern oil magnate, would force his twin sons David and Bill to resolve disputes by fighting each other in boxing gloves until they were exhausted. Another brother, the delicate Frederick, would deeply disappoint his father by embracing the worlds of art and culture.

The conflicts between the Kochs would echo throughout their lives as three of them became billionaires. Decades later, the quartet of brothers go at each other's throats in court as their elderly mother looks on in horror.

"Everything goes back to their childhood," says an unnamed relative. "Everything goes back to the love they didn't get." In a more gossipy and less authoritative book, this would seem like a nasty anonymous snipe. In "Sons of Wichita," it's a capstone to a case carefully made.

Their father is also key to the libertarian aspirations of David and his brother Charles, the two Koch men who've become household names by upending American politics. Fred Koch was a relentless anti-communist and committed fan of capitalism unfettered by rules and regulations unless they protected the system and men like him.

The elder Koch was "deeply paranoid," Schulman writes, and helped create the ultra-conservative John Birch Society while railing against supposed fronts for communism like higher education, tax-free non-profits, modernist art, and certain Protestant churches. (Oddly, the book doesn't delve into the faiths, if any, of the individual Kochs.)

The brothers soaked this up, with Charles going as far as embracing an eccentric libertarian guru devoted to free markets, pacifism, religious oddness, and the four women he lived with.

Libertarians, it turns out, can be quite the characters. Some of the most fascinating parts of "Sons of Wichita" chronicle the rise of the libertarian movement in the 1970s and 1980s.

The libertarians of that time were a motley mix of sci-fi geeks, free-market stalwarts, Ayn Rand enthusiasts, anarchists dressed in black, woolly-haired peace activists, and fans of sexual freedom. (David Koch, who lives a lavish playboy lifestyle like his brother Bill, was the vice presidential candidate on the Libertarian Party ticket in 1980. At the time, he favored repealing laws prohibiting "victim-less crimes" and targeting drug use and gays.)

The Koch brothers, all four of them, emerged from this period with the perennial problems facing the wealthy: More money, more problems, and plenty of what musician George Harrison called the "Sue Me, Sue You Blues."

Brothers faced off against each other and against their fun-loving and frog-hunting mother's new much-younger male friend. Bitterness reigned, and that's not all. Schulman describes a blitzkrieg of vicious accusations, privacy-busting investigations, and lurid details of a Koch brother gone wild. Pro tip: Don't fax explicit love notes to your paramour.

Other allegations were the stuff of the Wall Street Journal instead of the National Enquirer.

The Koch empire "developed a reputation as a corporate outlaw," allegedly stealing oil and harming the environment. Worse accusations would come in a horrific case of two teenagers killed by a massive natural gas explosion in Texas. With great detail and sensitivity, Schulman tells the tragic story of lives lost and destroyed.

The last chunk of "Sons of Wichita," starting with a chapter called "Out of the Shadows," explores how David and Charles Koch – tied as the sixth richest people in the world – created their political empire over the past five years. Their target: President Obama, a "hard core economic socialist" who'd "internalized some Marxist models."

The rest is recent history.

David and Charles Koch haven't succeeded in turning the country around as much as they'd like, and their popular portrayal as right-wing villains has shown that they're not made of Teflon, yet another product with a link to the Koch empire.

But, as "Son of Wichita" reveals, the brothers were fighters from the very beginning in a family forever devoted to conflict. They cannot be counted out.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.