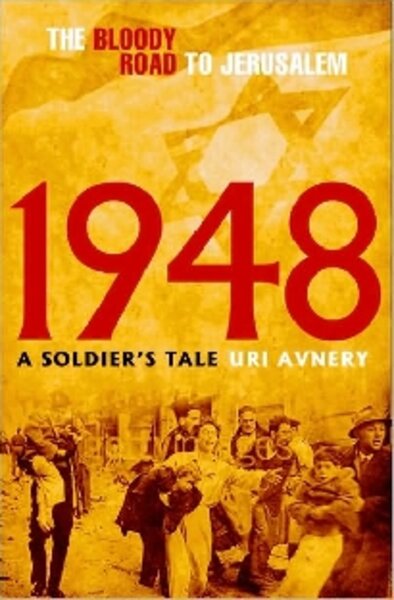

1948: A Soldier's Tale

Loading...

World War II had been over for less than three years when the 1948 Arab-Israeli War broke into a pyre of conflict that would blaze for decades. As a young infantryman in the Israeli Army, Uri Avnery was eyewitness to all of it.

He came away from soldiering not only with an intimate perspective on this particular war, but full of questions about the foundations of war in general.

The result was 1948: A Soldier’s Tale, originally published as two books in Hebrew in 1949 and 1950, but only now being released in English, this time as a single volume.

The first book, “In the Fields of the Philistines,” consisted of Avnery’s real-time dispatches, originally published in the Israeli newspaper Yom Yom (Day by Day).

The second, “The Other Side of the Coin,” was written in response to the success of “In the Fields of the Philistines.” Overhearing two young men bemoaning the fact that they had been too young to share in the “great experiences” recounted in his book, Avnery, in a matter of weeks, wrote a more candid account of his time in the Army, exposing the “awful side of the war” that he had assumed was apparent all along.

Avnery’s personal response to his time in the military has been to spend the rest of his life as a peace activist. (He is founder of Gush Shalom, the “Peace Bloc,” and recipient of the 2001 alternative Nobel Prize.) His stance on war is clear, but the value of his book lies in the arc it traces as he moves from plucky volunteer to war-weary “front ant.”

Avnery’s second book had a difficult time finding a publisher, even after the success of the first. And when it finally was published, the reception was hostile.

He portrayed Israeli soldiers as he saw them during the war: frequently thieving, sometimes murdering innocents, and contemplating rape. But what Avnery’s critics misunderstood was that his statement was never anti-Israeli, but, rather, antiwar.

“1948” is a tenacious attempt to communicate the reality of war. It has invited comparison to Erich Maria Remarque’s 1928 classic “All Quiet on the Western Front,” and deserves it.

Similarities between the two books stack up nearly one-to-one: War is never what anyone expects. Its effects are cruel and relentless, and even peace provides no escape. The impact on the modern reader is a dreadful déjà vu, but “1948,” being so close to present events, strengthens our appreciation of war as a baffling folly.

In the first part of “1948,” the tone is somewhat breathless, and the youthful zeal can seem a little incongruous, considering the grim content. Some entries are lighter. Avnery finds comfort in the building of comradeship and writes about the jaunty “sock hat” as a symbol of the optimistic emerging army. But everything has a monotone of introspection, and less of the emotional presence of the second part of the book, especially in the face of a young man’s discoveries of war’s ugliness. (“In the Fields of the Philistines” went through military censors when it was written, Avnery reminds us, which may explain the places where it seems shallow.)

“The Other Side of the Coin” takes place in the military hospital where Avnery was placed after being wounded in battle. This experience elicits particularly evocative passages regarding smells.

“War is not for people with sensitive noses,” concludes Avnery, “That may be one of the reasons most people don’t understand war. They see the pictures in the movie theater.”

As Avnery’s war experience grows, he begins to identify war as the common enemy. He asks why the two sides are still fighting when it’s apparent that all they really want to do is go home. “Of those who die in war only very few really wanted it. Those who wanted it are very rarely among the victims,” Avnery writes.

When a captured Arab dies, Avnery allows himself to meditate on the feebleness of the reason for it: because he was an enemy. “Think the word ‘enemy’ and your heart fills with hate.... But when you see the enemy with your own eyes, you see a person – like yourself.... How would it be if all of us – the Arabic speakers and the Hebrew speakers – got to know each other? Could we still hate each other then, kill each other?”

After indulging the fantasy of peace for a moment, Avnery snaps back to the life of a soldier with the dismissal, “Stupid ideas. He is dead and that is all.”

The vibration of Avnery’s life between extremes – thoughtful and reactive, human and animal – lets readers understand the soldier’s need for complete and rapid changes in order to survive.

Avnery’s self-awareness also helps to communicate the mentality of the soldiers at the front, the “front ants” who are the building blocks of any war.They are scoured by dirt, free of the pretensions of those at the rear, and for that matter, most signs of humanity. They care only for their duty to their comrades and for surviving after danger has passed. They are also next to helpless in determining their fate.

Although constantly hoping for a cease-fire, tragically, they are never the ones in a position to make decisions about peace.

Dan Fritz is a marketing coordinator for the Monitor.