Must an author’s wishes be honored after death?

Loading...

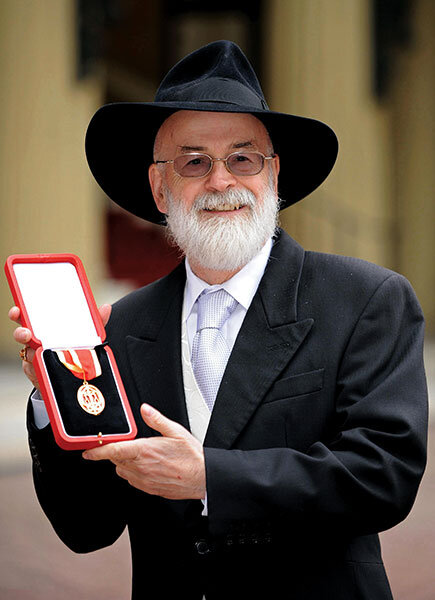

Authors once turned to fire to be rid of writing they didn’t want the world to read. Terry Pratchett took a slightly more creative – and modern – route. He ordered that his hard drive be crushed by a steamroller after his death. The destroyed drive is now on display at England’s Salisbury Museum.

The drastic action represents a new solution to a question that has plagued authors, their families, and their publishers for centuries: If an author doesn’t want his or her work published posthumously, must families and publishers comply – even if they believe the work is valuable? “You could say that on the one hand, an author should retain a kind of sovereignty over [his or] her unpublished material...,” says Paul Saint-Amour, Walter H. and Leonore C. Annenberg professor in the humanities at the University of Pennsylvania.

But what about the possible loss to world culture? Franz Kafka, for instance, told his friend Max Brod he wanted his unpublished works burned after his death. If Brod had done so, Kafka masterpieces “The Trial” or “The Castle” would have been destroyed. Was Brod right not to do so?

Sometimes an author’s desires are difficult to discern. The family of “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” author Stieg Larsson used another writer to complete one of his unfinished novels. But Larsson’s partner, Eva Gabrielsson, said Larsson would never have wanted that. “To Kill a Mockingbird” author Harper Lee was alive but older when her second work, “Go Set a Watchman,” was released in 2015. Questions were raised as to whether this was really Lee’s wish. (The Alabama Securities Commission stated that it was.)

Sometimes a good compromise can be delaying publication. Professor Saint-Amour points to “De Profundis,” Oscar Wilde’s 1897 letter to a male lover. The full text appeared in 1962 – long after the letter’s recipient and his family had died. Saint-Amour says, “I think that those surface solutions can be elegant in that they recognize the long-term cultural interest in a work while also recognizing that certain kinds of expressive works can be sensitive for the living.”