William Trevor, one of the world's great short story writers, remembered

Loading...

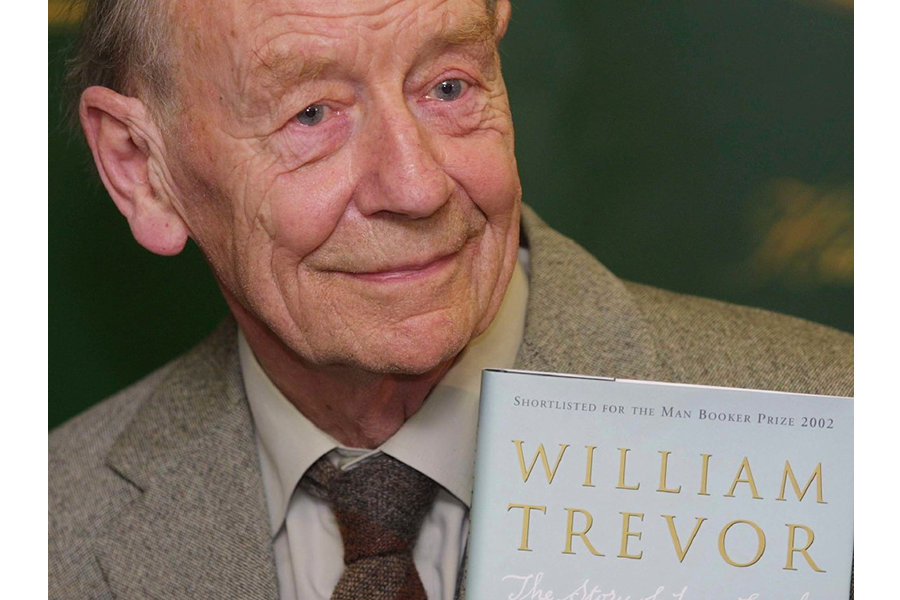

In a sad loss to the literary world, Penguin Random House Ireland has announced that Irish short story author William Trevor passed on at the age of 88.

Best known for his short stories, Mr. Trevor was a novelist, a sculptor, and a consummate artist whose works captured the unseen dark side of everyday life.

"If you take away the sadness from life itself," Trevor once told The Guardian, "then you are taking away a big and a good thing, because to be sad is rather like to be guilty. They both have a very bad press, but in point of fact, guilt is not as terrible a position as it is made out to be. People should feel guilty sometimes. I've written a lot about guilt. I think that it can be something that really renews people."

Trevor was born William Trevor Cox in Ireland in 1928. His parents, Protestants in a Catholic country, moved around frequently for the family patriarch's career as a bank manager.

Although Trevor eventually moved to an isolated mill in Devon, Britain, his Irish experience was evident in his stories, which focused on the small towns and hamlets of both Ireland and Britain. Trevor drew on decades of experience for his stories, often writing about sad and unusual people who lived in these small towns.

Trevor’s stories captured the struggles, both large and small, of the people who lived in these supposedly “backward villages,” finding the threads that bonded the village experience to the greater human struggle. Sometimes he wrote of the social and religious conflict between Ireland’s Protestant and Catholic communities. Sometimes he wrote about the rivalry among reunited schoolmates.

“The great challenge in writing is always to find the universal in the local, the parochial,” Trevor once told the Times. “And to do that, one needs distance.”

Although he is best known as a writer, Trevor started his career as a schoolteacher at a preparatory school in Northern Ireland. While teaching, Trevor began to dabble with sculpture. But it wasn’t until he began to write that Trevor truly found his art form.

In later years, Trevor would reflect that he loved writing because he loved people, telling the Times in 1990 that, “I sometimes think all the people who were missing in my sculpture gushed out into the stories.”

Indeed, Trevor’s popularity grew largely due to his ability to capture the truly human in his eccentric characters.

“Each character is somebody that I know very well – as well as I know myself. You become very interested in that person. You become immensely inquisitive and immensely curious,” he told an interviewer in the 1980s, as The New York Times reports. “I’m sort of a predator, an invader of people.”

A master of the art form, Trevor loved the necessary brevity of the short story, which he said he forced the author to expose the bare bones of truth.

“It should be an explosion of truth,” Trevor told the Paris Review. “Its strength lies in what it leaves out just as much as what it puts in, if not more.”

Trevor is survived by his wife of 64 years, Jane Ryan, and his two sons.