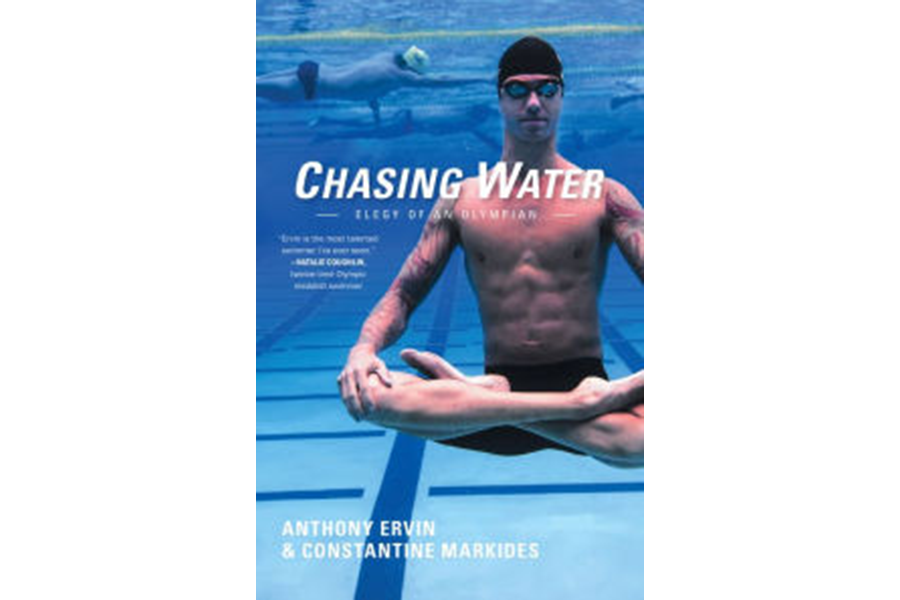

On the surface, a biography about a swimmer with just one individual Olympic gold medal might seem a stretch. Anthony Ervin’s story, however, transcends that shining moment in the 50-meter freestyle sprint at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, when he won a relay gold. After becoming the first swimmer of African American descent to medal in Olympic swimming, Ervin auctioned off his most prized medal in order to donate to tsunami relief. He retired from competitive swimming and entered a period of self-discovery that led to some questionable decisions and lessons learned the hard way. He resurfaced in 2012 to make the US Olympic team with a personal-best time, yet finished fifth at the Games in London. Now he’s training for a shot at swimming in a third Olympics this summer in Rio de Janeiro. His roller coaster ride to this point is told alternately by journalist and swim trainer Constantine Markides and by Ervin in his own revealing words.

Here’s an excerpt from Chasing Water:

“Ervin’s idiosyncrasy paradoxically was not so unexpected in the swimming world. Eccentrics are found in every sport, but swimming seems to attract, or create, them in abundance. Maybe it’s a product of the medium – complex, dynamic, unpredictable – or all that chlorine seeping into one’s pores, or the countless hours spent suspended in strenuous exertion, staring in virtual isolation at the pool bottom, lap after lap, like a suburban variation on Chinese water torture. Whatever the reason, swimming has an abundance of characters among both competitors and coaches, and not just its plebeian ranks: it’s wacky all the way up to the elite créme. In fact, it can be even more idiosyncratic up top since iconoclasm and outside-of-the-box thinking is often what it takes to stand out from the overwashed masses. On the other hand, the regimentation of workouts also generates a culture of intolerance in the swimming world toward those who disrupt that structure. Free spirits are tolerated, but only so long as they’re disciplined and compliant free spirits.”