Why Mindy Kaling's brother posed as black to get into med school

Loading...

Vijay Chokal-Ingam, who is sparking controversy with a proposed – but not yet finished book – "Almost Black – The True Story Of An Indian American Who Got Into Medical School Pretending To Be An African American," which he says is intended – at least in part – to balance the moral ledger.

“I’m a Hindu, and we have something called karma” says Mr. Chokal-Ingam, in an interview. “I think I’m doing the right thing now. I’m telling the truth about a system of organized racism that I don’t think helps anyone. I’m trying to prevent people from being discriminated against or having negative stereotypes created that hurt their careers indirectly through the cycle of discrimination.”

Chokal-Ingam, who subsequently dropped out of medical school and is now a graduate school admissions consultant, declined to speak about his family or his famous sister, the creator and star of the FOX comedy, 'The Mindy Project' and their reaction to his work.

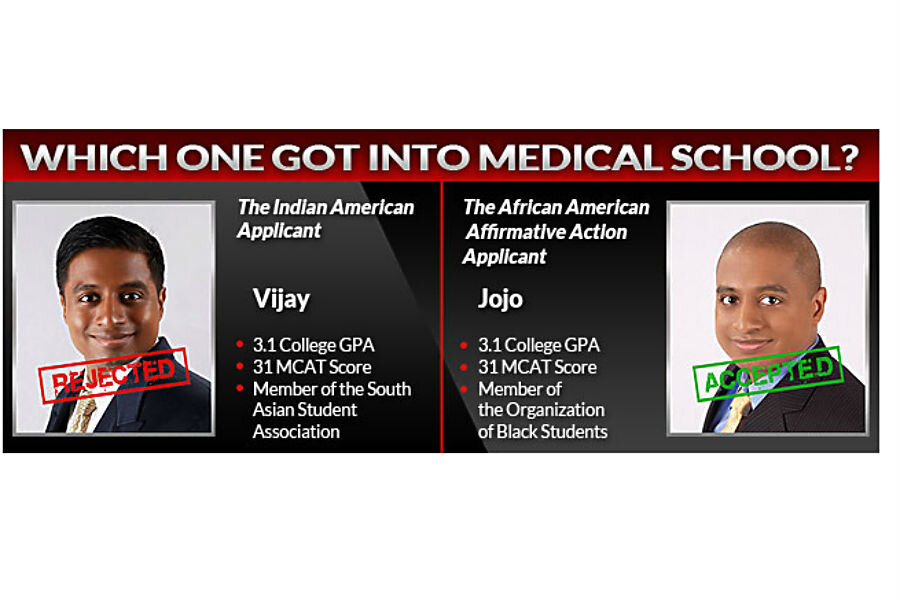

He describes how his decision to falsify his applications came about. “After watching some of my best friends who were Indian-American like me get rejected from medical school I said, you know, I don’t want to take the same path.”

“An applicant with my test scores who was Indian or Asian-American was unlikely to get into med school, while an African-American with the same scores was statistically likely to get into medical school. So it was a pretty easy choice at that point,” he says.

Chokal-Ingam says that it was at that point, “I chose to shave my head, trim my Indian eyelashes and join the organization of Black Students and apply to medical school as an African-American.”

Chokal-Ingam says he applied to a number of US medical schools, including Harvard, Cornell, and the University of Pennsylvania in 1998, adding, “I never lied about anything on my application, except my race."

Asked if he truly wanted to become a physician or if this was a social experiment, he says, “At the time there was nothing I wanted more in the world. My mother was a doctor. I’d worked in a hospital. There was nothing I wanted more and I was willing to do anything within reason to achieve that goal.”

But he never completed his medical training, a fact that he attributes to karma.

“I have to be willing to accept the fact that perhaps I was never destined to become a doctor because of the way I got in,” he says. “I showed that I didn’t have the clinical skills required to be a doctor. So unfortunately, I dropped out.”

He went to business school at UCLA, which he says “did not have affirmative action and so accepted me purely on my merits.”

Now, however, he says the school has become privatized since his graduation, and there is currently a push to institute an affirmative action admission policy.

Chokal-Ingam says he experienced racism daily while posing as an African-American man.

“I would walk into Mr. G’s market where I’d shopped for years and I was accused of shoplifting,” he recalls. “I was constantly pulled over by police for driving a nice car with them saying ‘Do you know how expensive the car you’re driving is?’"

Yet, despite seeing racism first hand, he says, “Discrimination in the form of racism is not the answer to our country’s racial problems.”

Dennis Parker, director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Racial Justice Program, takes issue with Chokal-Ingam's analysis.

“What I think disturbs me most about this, and there’s a great deal to choose from here, is that here is a man who has been privileged to drive down the street and go into a market without experiencing racism who got to see it from the other side and was able to just walk away from it unchanged.”

“He took away from that, not that he should champion or advocate for people who don’t have the luxury of walking away from discrimination and racism and instead looks all these years later for his own self-interest," Mr. Parker adds.

Chokal-Ingam says that he understands the backlash he is getting on social media, which he characterizes as coming from African-Americans, “who have experienced racism in their lives and they are very angry about the experiences they’ve had.”

But he says that his book, if published, will be designed to help African Americans.

“In business school we say that ‘perception is reality.’ There is a perception, a stereotype that African American and Hispanic professionals are not as competent as their peers and, unfortunately, affirmative action is designed to give them special treatment that perpetuates that myth,” he says. “That is more damaging than any temporary, transitory benefits from affirmative action. Although, of course, there are definitely social wrongs that need to be addressed.”

“There are about 15 different ways to go at this [claims made by Chokal-Ingam], one more infuriating than the next,” Mr. Parker says. “To contend that people of color who are unqualified are being let into schools is wrong and offensive. His [Chokal-Ingam’s] statements strike me as being completely a-historical. The very idea that black people became stereotyped because of affirmative action is ludicrous.”

Twitter erupted with conflicting views.

Parker adds that American culture and society has a long way to go before it will be ready to abolish affirmative action and not suffer the consequences of flagging enrollment among African American students, such as the declines that have sparked debate in California and Florida.

“Before you eliminate affirmative action, you need to be sure you eliminate racial inequality; have an unemployment rate for people of color that isn’t twice as high as whites. Also, show that white wealth isn’t consistently higher than that or people of color and that educational opportunities aren’t tied to wealth in America,” Parker says.

Asked if he would make the same decision all over again Chokal-Ingam says, “I know what I did was wrong. Things you do at age 22 are not the same things we choose to do at age 38.”