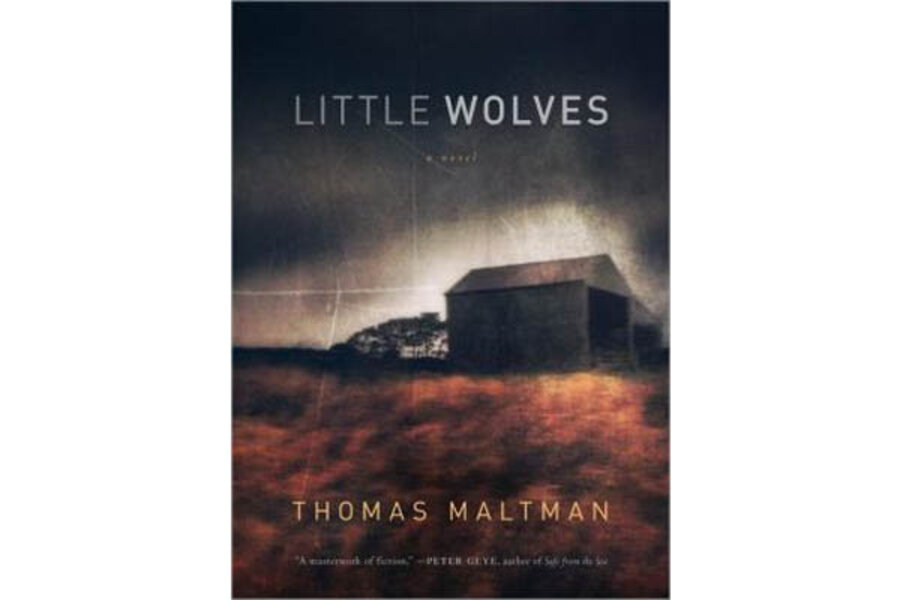

A teenage boy comes to town in a duster and sawed-off shotgun. He knocks on his teacher's door before killing the sheriff in Thomas Maltman's Little Wolves.

What happened before high-schooler Seth Fallon was found dead in a corn field is a mystery that drives both his dad, Grizz Fallon, and his teacher, Clara Warren, the new preacher's wife and an Anglo-Saxon scholar.

The rest of the town wants to bury Seth in the suicides' corner of the graveyard, along with any secrets that might have explained what happened that day.

Clara, who is six months' pregnant, had her own reasons for moving to Lone Mountain, Minn., with her priggish pastor husband. She's seeking clues to her mother's death in the dark fairy tales her dad told her as a girl.

She finds herself haunted by her failure to answer the door that day, wondering if she could have stopped Seth, or if she would have been the first victim.

To be frank, I had no desire to read about a teenage boy with a gun so soon after the Sandy Hook murders, but “Little Wolves” is as far from Jodi Picoult-style fiction as you can get and still be shelved in the same library.

At its heart, “Little Wolves” is a powerful mystery (with maybe a few too many poetic overtones). With a lyrical style that is anything but ripped from the headlines, Maltman combines mythology and small-town claustrophobia to show how the roots of the violence were planted before Seth was born.