He robbed banks for four decades without firing a shot and broke out of three maximum-security prisons. His eyes were so blue the FBI described them as “azure.” He was even called “The Actor.” How has there not yet been a movie about Willie Sutton?

“In his heyday Sutton was the face of American crime, one of a handful of men to make the leap from public enemy to folk hero. Smarter than Machine Gun Kelly, saner than Pretty Boy Floyd, more peaceable than Dutch Schultz, more romantic than Bonnie and Clyde,” writes J.R. Moehringer in his debut novel, “Sutton,” possibly gold-plating the Thompson sub-machine gun. “He was Henry Ford by way of John Dillinger – with dashes of Houdini and Picasso and Rasputin.”

Moehringer has said in interviews that he was motivated to write Sutton after the 2008-2009 crash brought on by the housing bubble and reckless decisions by bankers. If you want to be a prophet, just predict another crash, Sutton tells an interviewer. “Times are hard, people are fed up. Prices are soaring, taxes are sky high, millions are hungry, angry. Injustice. Inequality,” a character sums up. Sound familiar?

He's not the only one to see parallels between the robber who preyed on banks and the people running them: a 2011 documentary, “In the Steps of Willie Sutton,” followed a similar path as his novel.

Sutton opens on Christmas Eve 1969, when the ailing convict is released on a pardon. He spends Christmas Day with a newspaper reporter and photographer taking a tour of his old haunts, from the slums where he grew up to the site of his first robbery. What he won't do is tell them whether he was responsible for the hit on Arnold Schuster, the 34-year-old who spotted one of the FBI's Most Wanted on the street and turned Sutton in.

To hear Willie tell it, his life of crime was the result of thwarted love: He and heiress Bess Endner wanted to get married, but her dad would have none of it. At Bess's urging, he, Bess, and Happy, a childhood friend, robbed the safe and headed out of town. Sutton's career, as he sees it, is an effort to get back to Bess. Unfortunately, the blue-eyed blonde just doesn't captivate readers the way she does Sutton.

Moehringer drops clues that Willie might not be rock-solid reliable as a narrator, which helps, but “Sutton,” whose protagonist spent more than half his adult life behind bars, still drags in spots. Most of the robberies are summed up or seen from the distance of time, which saps a lot of suspense.

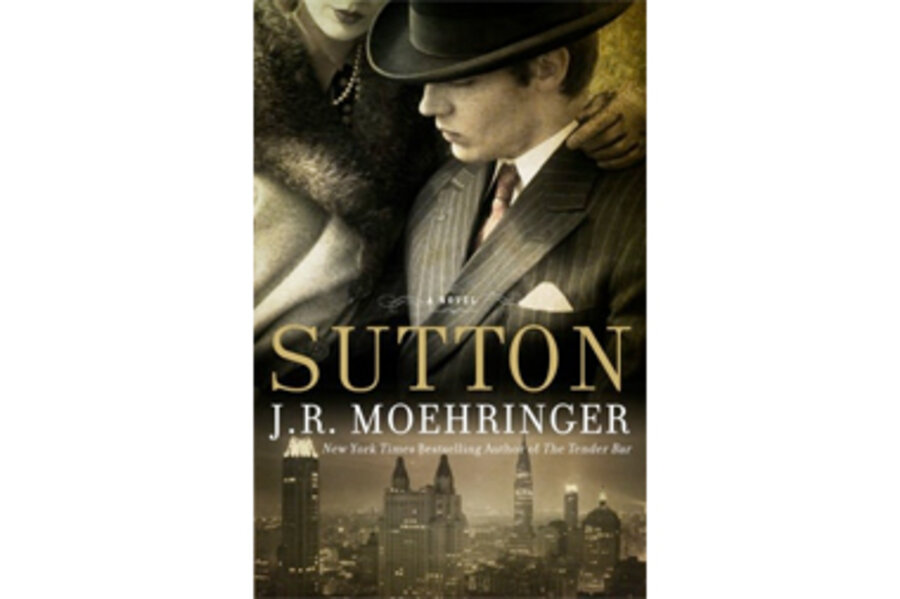

Moehringer won a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times and also wrote the highly regarded memoir “The Tender Bar.” His skills as a reporter and a memoirist would have been vital trying to crack the psyche of a man who wrote two memoirs of his own – which contradicted each other – and who claimed he never said his most famous line. Why rob banks? “That's where the money is.”

The only trouble with Sutton's law, as it's become known: “One of your colleagues invented that line kid. Put my name to it.”

The dialogue is reminiscent of Bogart, with Sutton calling the reporter and several other characters “kid.” Occasionally, it's so stylized as to grate, as when Sutton tells the reporter, whose name we never learn, “In the joint, kid, thinking is the one thing you can't let yourself do.”

The Bogart influence seems by design, with Sutton name-checking him and James Cagney: “Every criminal is playing some criminal he saw in a movie.”

After robberies, he said, he and his accomplices would run straight to the newsstand to check out “their reviews.” If the article said that police thought the crime looked like the work of amateurs, “we'd go into a funk for a week.”

The question, then: Who was Sutton playing, and, by the end, could he even tell the difference between himself and his role of a lifetime?