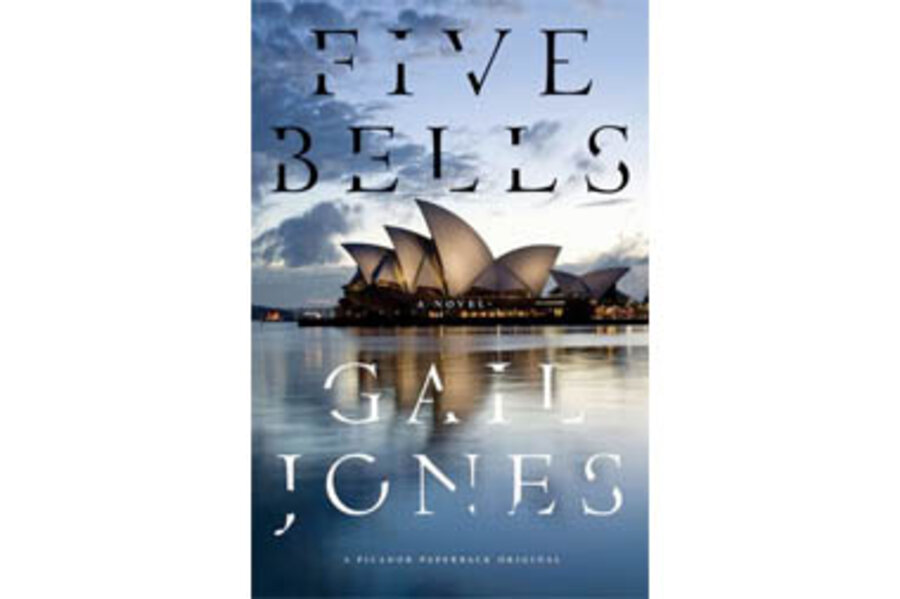

Sydney's iconic tourist attraction is the setting for Australian novelist Gail Jones's “Mrs. Dalloway”-like novel, Five Bells. Over the course of one Saturday, four different people converge on Circular Quay and the Sydney Opera House, which looks like shark's teeth, origami, or stacked porcelain bowls, depending on who's doing the viewing.

Sunny Ellie is looking forward to a reunion with her first love, James, who's struggling under the weight of a recent tragedy. Catherine, an Irish journalist, is mourning her brother, who was killed in a car accident. But the heart of the novel belongs to Pei Xing, whose parents vanished during Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution and who endured her own imprisonment and torture. (In fact, her story is so compelling, I resented it whenever vapid Ellie showed up to interrupt.)

All of them observe the same seemingly-innocuous events, whose import becomes clear only later, as they reflect on their pasts. Jones, who has been nominated for both the Man Booker and Orange Prizes, has her characters intersect in glancing ways. She also evokes other novels throughout “Five Bells,” ones that offer a chill one wouldn't expect on a summer day. “Dr. Zhivago,” which Pei Xing's father translated from Russian, gets pride of place, with its many descriptions of falling snow. For her part, Catherine is haunted by James Joyce's short story, “The Dead,” which ends with “snow falling on all the living and the dead.”

“Five Bells” is a highly constructed novel – readers who prefer a more conversational style may chafe at connections that strike them as forced. But Jones is an elegant writer, and those who like a little literary in their fiction will find plenty of meaning in the echoes coming from the direction of the Opera House.