China's citizen petitioners find cold reception in Beijing

Loading...

| Beijing

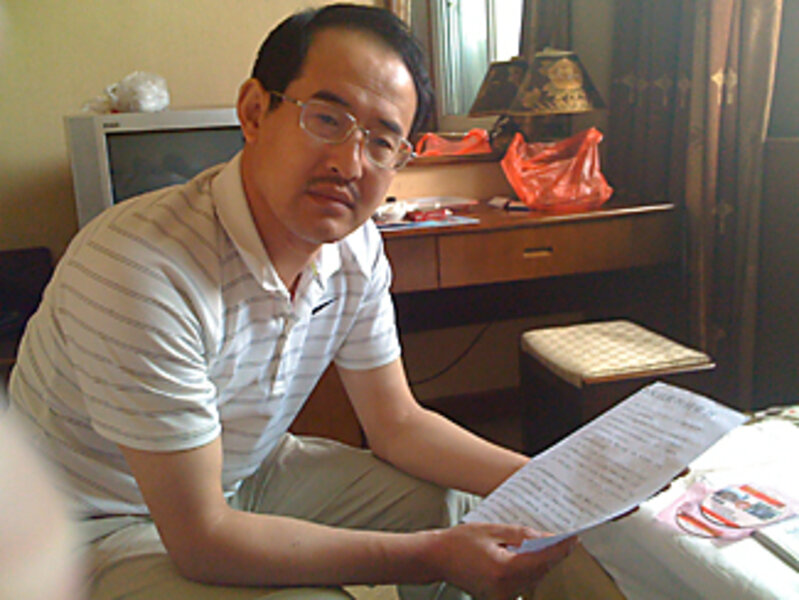

Yu Tong'An had high hopes last Tuesday morning as he stood in a Beijing park surveying a group of some three-dozen parents who believe that their children – like his teenage son – have been sickened or killed by mandatory vaccinations.

At last, he thought, enough victims had gathered to make their demand for justice heard at the highest levels of government.

"The Chinese government does not like ordinary people to get together, but that's what we have to do," he said.

A week later, disconsolate and disillusioned, Mr. Yu, a peasant farmer, was taken back to his village in southern China by local officials sent to the capital to catch him. He has not been heard from since he boarded a plane at lunchtime on Monday.

"Frankly, I do not know my next step," he had said shortly before he left. The only Health Ministry official he had been allowed to see "just lied to us," he lamented. "Officials don't deal with our problem. They just kick it from office to office."

Yu's story offers an unusual glimpse into the desperate world of Chinese petitioners seeking redress from central government for wrongdoing by local authorities.

It is a centuries-old tradition that Beijing is keen to stamp out, especially in the runup to important events such as the 60th anniversary of the People's Republic of China Oct. 1, when the government hopes to present an image of national harmony.

Provincial governments, fearful that citizens might reveal their failings to higher officials, can take extreme measures to derail such critics. Often, they send policemen to Beijing to track petitioners down and stop them from filing their complaints. Sometimes they hold petitioners in illegal "black jails."

Tactic: wear them down

Yu and his fellow protesters, who came from all over China, suffered no such fate last week.

Instead, officials chose to simply wear them down. Perhaps their distress provoked sympathy: they say that their children became crippled after taking polio vaccine or brain-damaged after meningitis vaccine in what appeared to be catastrophic malfunctions of government health drives.

Some have been denied any compensation at all, and have been impoverished by the costs of caring for and treating their children; others complain that the money they had been given was insufficient; yet others say they simply want justice.

"I want the government to punish the official who caused this," said Wang Mingliang, whose 9-month-old daughter died last year after a meningitis vaccination and who claims to have evidence the vaccine was improperly stored.

Almost all the parents seeking redress have secured medical opinions from local hospitals tying their children's death or illness to the vaccinations.

Organizing over IM

Quietly, for a month or so, the parents used Instant Messaging to plan their action in the capital, they explained. Yu, a serial petitioner, says suspicious local officials offered him 6,000 RMB ($830) in what they called a "stability maintenance fee" to remain under house arrest until the end of the 60th anniversary festivities.

Instead, he gave police the slip, he says, and took a roundabout railroad journey to Beijing. Using a precaution familiar among petitioners, he removed the battery from his cellphone so that the police would not be able to track him using GPS.

Once in the capital, he joined other protesters at a clandestine hotel, where nobody asked to register his ID card.

The parents, some cradling their crippled children, first sought an audience at the Health Ministry on Tuesday afternoon. A junior employee met them on the sidewalk and took their personal details before disappearing back into the ministry.

Those details, it seems, were quickly communicated to the protesters' local governments. The next morning, when they returned to the ministry, several of them saw familiar faces among the onlookers – policemen, local Communist party secretaries, county-level petition office bureaucrats, and other officials from their home towns.

None of them made a move, however, when parents forced their way through security gates onto the forecourt of the ministry and unfurled a banner asking "Our children took a tablet: Who is responsible for their disability?"

That could have earned them a beating by police. Other protesters have suffered that and more, according to international human rights groups. In fact, they vacated the ministry quietly when the police were called, and accepted an offer of lunch from the head of the Health Ministry's petition office, who identified himself only as Mr. Zhang.

Mr. Zhang was polite, and listened to their complaints one by one, several petitioners recounted. But he did not give them the slightest satisfaction.

He said he would order local governments to solve their problems, "but we already know that local governments won't deal with this," said Yi Wenlong, a former trucker who gave up his job two years ago in order to pursue the case of his brain-damaged daughter. "Zhang is just trying to shift the responsibility onto someone else."

It was then that the parents began to bicker among themselves over what to do next. "Because we don't have a leader, our organization is not very good," acknowledged Mr. Yi.

Some wanted to make a dramatic move – throwing themselves into the moat surrounding the Forbidden City, for example. Others simply gave up and returned home. Yu and three other fathers stayed on in Beijing, pondering their options.

They didn't appear to have any new ideas, though, and knew that they could not stay indefinitely. "It's not a question of how long we want to stay," said Yi. "It's how long the officials will allow us to be here."

He and a friend returned to their home province of Shanxi on Friday, in hopes of meeting a journalist from a national newsweekly who was said to be investigating the vaccine story.

On Friday evening, Liang Yongli, another petitioner, agreed to meet local officials who had been hounding him by phone for days. He was detained, he recounted later, held in a hotel overnight, and then forcibly put on a plane to Guangzhou.

On arrival in his home district of Xinhui, he said, he was taken to the local Communist party school, where current party cadres are trained. "They said they kept me to study, but actually it was detention," he complained.

Mr. Liang's daughter, along with Yu's son, were among six children over a two-year period who suffered brain damage after meningitis vaccinations in the same hospital in Guangzhou, Liang said.

He was freed Monday only after his wife and daughter protested outside the municipal government building. "How can they be so dark?" asked his wife, Liu Xueyun, bitterly. "I thought [the Communist party] was a good party, but how could they detain innocent people?"

Liang said he was forced to sign a pledge not to return to Beijing until after the 60th anniversary holiday is over.

Giving up in defeat

Yu, meanwhile, gave himself up on Monday morning, defeated.

"I'm on my own now," he had said in a telephone interview the night before. "My power and capacity are too little. I'm very sad."

Officials from his village had promised to help pay his son's medical bills, he said, and to pay his "stability maintenance fee," even though he had defied them and come to Beijing. "I don't know whether they will keep their promises, though," he added.

At noon on Monday, Yu called his wife to tell her he was getting on a plane home, his wife said. As of Tuesday evening she had heard nothing from or about him since.