In exile 50 years, will the Dalai Lama ever return to Tibet?

Loading...

| Beijing

Half a century after the Dalai Lama fled Tibet after a failed uprising against the Chinese, the question of whether he will ever return is growing increasingly urgent.

In Tibet itself, "strong pressure is building, more than at any time previously, for him to be allowed to come back," says Robbie Barnett, a Tibet expert at Columbia University in New York.

The Dalai Lama, however, considers his return as "the least important question," says Pico Iyer, who recently published a book based on a series of conversations with the Tibetan leader. "He says that his only real concern is the welfare of the 6 million Tibetans."

Either way, on Monday, the day before Tibetans worldwide mark the anniversary of his flight, Tibetan monks in the Indian town of Dharamsala, home of the Tibetan "government-in-exile," led "long life prayers" for the Dalai Lama, who turns 74 in July.

In a bid to forestall protests marking the anniversary, the Chinese government has blanketed Tibet and neighboring Tibetan-inhabited areas with Army and police forces, according to reports by local residents. The authorities say they are determined to prevent a repetition of the unrest that spread widely across the Tibetan plateau a year ago this week.

The heavy security presence, and the ban on foreigners entering Tibet or neighboring provinces that has been in force for several weeks, according to travel agents, cast doubt on Chinese claims that ethnic tensions are not high. In addition, two police cars were damaged by explosive devices Monday in the heavily Tibetan western district of Qinghai Province, the official Xinhua news agency reported.

"The stringent security indicates a failure of Chinese policy on Tibet," argues Kate Saunders, spokeswoman for the International Campaign for Tibet (ICT), which advocates greater freedom for Tibetans.

Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama has himself acknowledged the "failure" of his own policy of talks with Beijing that have yielded no results. "Our approach never affects the inside situation" he told reporters in Japan last November. "Things are not going well."

The perspectives expressed by the Dalai Lama and Chinese officials on Tibet could not clash more directly. The man who acts as his people's spiritual and political leader talks of "cultural genocide" by the Chinese, and warns that Tibet's "ancient culture and ancient civilization are now dying."

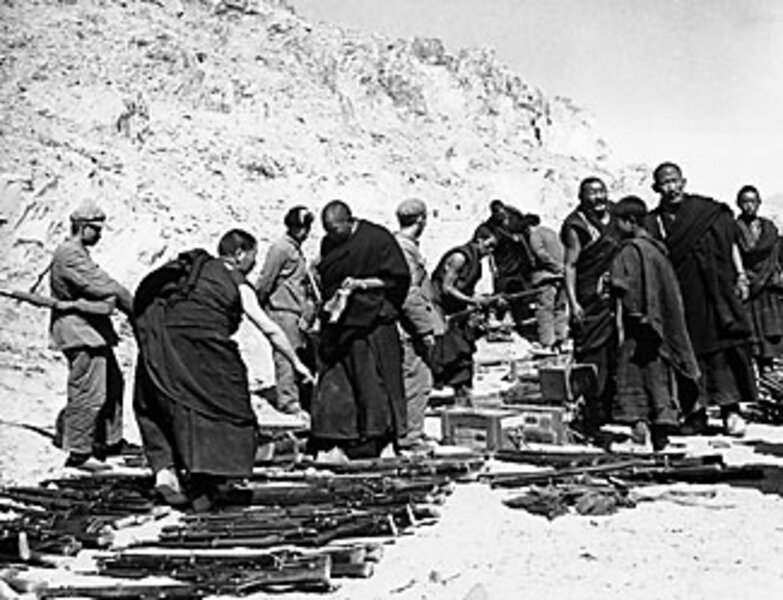

The Chinese authorities, at least in their more polite moments, claim that since the Dalai Lama's "system of theocratic feudal serfdom" was overthrown by Beijing 50 years ago, Tibet "has experienced a process from darkness to lightness," in the words of a government report issued last week.

More bluntly, some senior officials have taken to referring to the Dalai Lama as "a beast" set on snatching Tibet away from Chinese sovereignty. The stepped up vitriol, such as a recent editorial in the official Tibet Daily calling on people to "firmly crush the savage aggression of the Dalai clique," "makes the possibility of the Dalai Lama's return seem quite remote at the moment," says Ms. Saunders.

The Dalai Lama himself has acknowledged that "for the short term, the Tibet issue is hopeless," but still holds out hope that "when the time comes I will return with a reasonable degree of freedom" and hand over all his authority to a local government in Tibet running an autonomous administration under Chinese sovereignty.

At the same time, says Mr. Iyer, the Dalai Lama worries that his mere presence in Tibet would act as "a magnetic center" for anti-Chinese sentiment. His reception, likely to be ecstatic, would only dramatize the way in which many Tibetans feel loyal to him and not Beijing, and distract from resolving the deeper problems faced by Tibetans.

In Tibet itself and in Tibetan areas nearby, the Dalai Lama has become "the central image in protests," says Professor Barnett, suggesting that as political discontent spreads "increasingly a lot of people want him back under any conditions, even if it achieves nothing with the Chinese.

"The feeling that Tibet is deeply incomplete without him being there is a very strong feeling and it seems to be growing," Barnett adds, although there seems to be no chance that the Chinese government would let the Dalai Lama do more than visit Tibet occasionally, even if he lived in Beijing.

Tibetans' anxiety is sharpened by their leader's age and apparently weakening health; he has spent time in Indian hospitals four times over the past year, and has recently trimmed his busy schedule of meetings, teaching, and foreign trips.

There is a suspicion among foreign analysts of Chinese policy toward Tibet that Beijing has no intention of seriously seeking a solution to the problem and is planning simply to wait for the Dalai Lama to die. His successor, after all, would enjoy none of the international kudos, domestic devotion, or diplomatic experience that gives the Dalai Lama his political strength.

That would be unwise, cautions Iyer. "The Dalai Lama's fear is that once he and his restraining influence are gone, Tibetans will act on their frustrations, and maybe act violently," he says.

Since the last round in November, talks between top Chinese officials and delegates of the Dalai Lama, which have occurred sporadically since 2002, appear at an impasse. The Chinese side has repeatedly refused the Tibetans' demands to discuss the outlines of Tibetan autonomy, calling that plan "covert independence" and a violation of Chinese sovereignty.

Frustration at the lack of progress in these talks, and general political discontent, seems to be deepening among many Tibetans, say Barnett, pointing to the geographical spread of demonstrations last year and to continued reports of protests.

"Things are more critical than they have been for many, many years," Barnett warns. "This is a tinderbox, and the Chinese are very aware of that."